Some books are suitable for long, discursive reviews, with extended explications of theme and metaphor. And some books are best served with plot summaries mixed with consumer information. Yet others reward deeply idiosyncratic, individual reactions, with a focus on a particular reader's thoughts while reading that book. And some books just leave a reviewer pointing and jabbering, unable to coherently explain what he's just been through or to find any words that will adequately explain what he has seen.

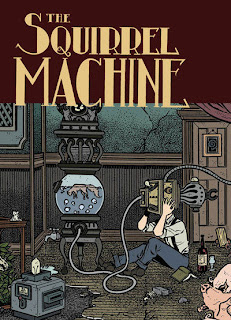

Some books are suitable for long, discursive reviews, with extended explications of theme and metaphor. And some books are best served with plot summaries mixed with consumer information. Yet others reward deeply idiosyncratic, individual reactions, with a focus on a particular reader's thoughts while reading that book. And some books just leave a reviewer pointing and jabbering, unable to coherently explain what he's just been through or to find any words that will adequately explain what he has seen.The Squirrel Machine is a book of the fourth kind; it has a superficially linear plot -- broken only by being told slightly out of order -- about two scientifically adventurous boys in a steampunky semi-rural 19th century setting, but the details of that setting, and of their scientific explorations, cannot be easily described. (In fact, they may not be clearly describable at all.)

William and Edmund Torpor are introduced as men in their later years -- one massively obese and bed-bound -- but it quickly moves back to their boyhood, where they were misfits, friendly only with each other. They live in the farmlands surrounding the small city (or large town) of Clemens, where they are at best tolerated out of respect for their widowed mother. They spend most of their time, apparently, in odd scientific experiments, most of which take place in an extensive set of underground rooms and passages.

But we don't see the boys actually building any of the biomechanical contraptions that they are obsessed with, nor do we see them creating or maintaining the massive complex of rooms underneath them. The reader presumes that the boys are responsible for the machinery and the rooms -- simply because there's no one else who could have done it, unless some of the machinery is now self-directed -- but that remains a presumption. The Squirrel Machine is a book in which nearly everything important happens offstage, for inexplicable and unknowable reasons, and in which the motivations of these two boys -- and the two vastly different young ladies that they become involved with -- are equally opaque.

Reading The Squirrel Machine is very much like watching some German Expressionist movie: it's a series of alternately wondrous and appalling scenes, clearly connected by some kind of logic, the true meaning of which resolutely remains beyond the knowledge of the viewer. It's certainly an impressive achievement, but, even a week after reading it, I still have no idea what to think of it.

Book-A-Day 2010: The Epic Index

----------------

Listening to: Haley Bonar - Devilish Man

via FoxyTunes

1 comment:

I think OMGWTFBBQ is a good start...

Then go on and read Chloe and some of the various Chrome Fetus comics and your brain will probably cave in.

Rickheit is someone I cannot help reading, but he scares me - even more than Al Columbia.

Post a Comment