When I was young and thought that I wanted to be a writer, Raymond Carver was a god. Not my god, though: my gods had names like Silverberg and Wolfe and Zelazny and a different Raymond named Chandler. But a little bit in highschool and a whole lot in college, Carver's minimalism was the epitome of what a would-be writer was supposed to aspire to, the template of what we should be trying to achieve.

I was reflexively contrarian in those days -- perhaps not so different now, though maybe more self-knowledgeable about it -- so I avoided Carver at every turn. I didn't want to travel his route, I didn't want to be influenced by him, I didn't want to read him, I barely acknowledged that he even existed.

Thirty years later, though, Carver is dead and I'm not a writer. So the question of which writers I'm not like is purely academic, in dustiest medieval-scholastic style. And so I finally found time to read Carver's Cathedral, one of his major short-story collections. It was originally published in 1983 and reprinted in paperback in the fall of 1984 for the launch list of Vintage Contemporaries, which is why I came around to it now.

Cathedral has a dozen stories about small-time people and their small-time lives: living in cheap furnished apartments, working as chimney sweeps or at "the plant," getting by but no more than that. Their landscape is the mid-20th century, domestic edition; the stories take place in living rooms and kitchens, mostly, with people who smoke and drink too much and whose intimate relationships are very likely to have just fallen apart. So call it grubby realism, call it kitchen sink drama: it's close to the cliche about literary fiction, though there are no professors here. No one in Carver's world is a professional or a success: there might be a highschool art teacher but not anyone tenured, and if anyone works at a hospital it would be a janitor rather than a doctor.

They're inarticulate people, too: they can't say what's wrong with their lives, because they don't have the words to describe it. When the estranged wife calls from California, where she's run off with another man to find herself and become an artist, Carver's narrator can't yell at her or lash out, so he just sits there quietly and says standard bland pleasantries while she natters on about her self-actualization. So Carver can't have them explain themselves or their lives to us, and his narrative voice is stripped down and stark, too [1]: we have to feel it for ourselves.

And yet it works. More than that, it works brilliantly: Carver really does craft epiphanies out of this incredibly unlikely material, and makes stories that have an amazing Everyman appeal because of that kitchen-sink-ness. After all of these years, it turns out my professors were right: who would have thought it?

[1] Although it turned out that voice didn't really originate with Carver himself but was imposed on him in slashing edits by Gordon Lish of Knopf.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

A Weblog by One Humble Bookman on Topics of Interest to Discerning Readers, Including (Though Not Limited To) Science Fiction, Books, Random Thoughts, Fanciful Family Anecdotes, Publishing, Science Fiction, The Mating Habits of Extinct Waterfowl, The Secret Arts of Marketing, Other Books, Various Attempts at Humor, The Wonders of New Jersey, the Tedious Minutiae of a Boring Life, Science Fiction, No Accounting (For Taste), And Other Weighty Matters.

Wednesday, December 31, 2014

Tuesday, December 30, 2014

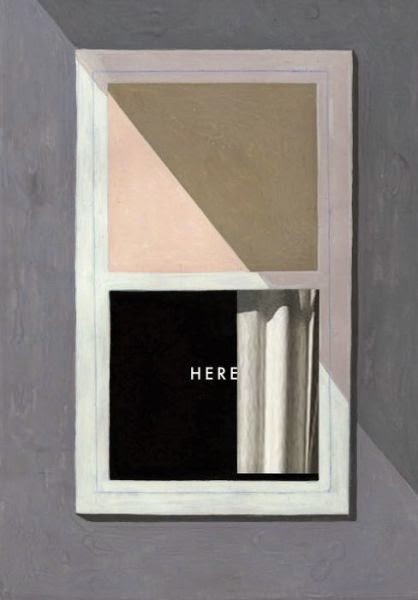

Book-A-Day 2014 #364: Here by Richard McGuire

We think we know how comics work: panels are placed in sequence on a page, and the eye tracks from one to the next. Each panel is a moment in time, and the moments connect to each other to show a sequence of events. There can be flashbacks or flashforwards or fancy page layouts, but there are always panels in a sequence, right?

In 1989, Richard McGuire showed us otherwise, with a six-page story called "Here" in the first trade paperback issue of the influential anthology RAW. [1] That story showed the corner of a room: each page had a six-panel grid, and each panel was locked down to the same view of that room. But, within that view, other panels popped, to show different times in the same place -- sometimes in close succession, like one panel showing a woman cleaning the room in four consecutive years, but sometimes only connected by theme or concept. The house was built in 1902 and burned down in 2029, but the panels ranged further in time than that, before and after the house even existed. McGuire's art was more workmanlike than evocative, but the concept was electric: comics could radically change their viewpoint and still be recognizable comics; they could use place to unify a story rather than character or time.

Twenty-five years later, McGuire took the same concept and blew it up to book length. Here doesn't incorporate any of the art from the original story -- it's in flat color, with a multimedia look, as if it were partially hand-drawn but assembled in a computer program, and it's much more immersive and flexible than the original short's art style -- and doesn't replicate the same physical layout, either. Instead, McGuire uses each spread as a view, to show most of this one room -- or the space it encompasses -- a hundred and fifty times, sometimes mostly the same year, and sometimes fragmented into a dozen different smaller panels of different people and actions and times.

doesn't incorporate any of the art from the original story -- it's in flat color, with a multimedia look, as if it were partially hand-drawn but assembled in a computer program, and it's much more immersive and flexible than the original short's art style -- and doesn't replicate the same physical layout, either. Instead, McGuire uses each spread as a view, to show most of this one room -- or the space it encompasses -- a hundred and fifty times, sometimes mostly the same year, and sometimes fragmented into a dozen different smaller panels of different people and actions and times.

The book Here gives McGuire the scope to explore the concept he could only sketch in the original story: he has space here to give us snapshots of two centuries of this house's existence, and of events before and after that, from dinosaurian prehistory to an equally lush post-history hundreds of thousands of years in the future. We learn a few names, but we recognize characters mostly from there years -- we see five children grow up through the '50s to the '70s, and see them and their parents across four decades. We see others in moments: two local Amerindians in courtship in 1609, Ben Franklin visiting his son's house in 1775, other families that live in the house in the 1990s and 2000s, a painter and his girlfriend on the grass in 1870.

The exact details are different -- in Here, the house was built in 1907 and flooded in 2111, spending most of the next century underwater -- but the style and the method of making connections is the same as in "Here," only refined and expanded into something magnificent and wondrous. It's rare to be able to honestly say so, but Here is a unique book, one that tells its stories in a way no one else has and that makes connections in ways unexpected and fascinating.

Here is a magnificent achievement that stands entirely alone; Richard McGuire has turned everything we thought we knew about comics sideways and made great art in the process.

[1] The original story is available online; I believe with the author's permission.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

In 1989, Richard McGuire showed us otherwise, with a six-page story called "Here" in the first trade paperback issue of the influential anthology RAW. [1] That story showed the corner of a room: each page had a six-panel grid, and each panel was locked down to the same view of that room. But, within that view, other panels popped, to show different times in the same place -- sometimes in close succession, like one panel showing a woman cleaning the room in four consecutive years, but sometimes only connected by theme or concept. The house was built in 1902 and burned down in 2029, but the panels ranged further in time than that, before and after the house even existed. McGuire's art was more workmanlike than evocative, but the concept was electric: comics could radically change their viewpoint and still be recognizable comics; they could use place to unify a story rather than character or time.

Twenty-five years later, McGuire took the same concept and blew it up to book length. Here

The book Here gives McGuire the scope to explore the concept he could only sketch in the original story: he has space here to give us snapshots of two centuries of this house's existence, and of events before and after that, from dinosaurian prehistory to an equally lush post-history hundreds of thousands of years in the future. We learn a few names, but we recognize characters mostly from there years -- we see five children grow up through the '50s to the '70s, and see them and their parents across four decades. We see others in moments: two local Amerindians in courtship in 1609, Ben Franklin visiting his son's house in 1775, other families that live in the house in the 1990s and 2000s, a painter and his girlfriend on the grass in 1870.

The exact details are different -- in Here, the house was built in 1907 and flooded in 2111, spending most of the next century underwater -- but the style and the method of making connections is the same as in "Here," only refined and expanded into something magnificent and wondrous. It's rare to be able to honestly say so, but Here is a unique book, one that tells its stories in a way no one else has and that makes connections in ways unexpected and fascinating.

Here is a magnificent achievement that stands entirely alone; Richard McGuire has turned everything we thought we knew about comics sideways and made great art in the process.

[1] The original story is available online; I believe with the author's permission.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Monday, December 29, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #363: Ricky Rouse Has a Gun by Tittel and Aggs

Stop me if you've heard this one before: a man, a tough man, runs away from his responsibilities after a bad breakup. He runs to a foreign country, drinks too much, sleepwalks through bad jobs, hits bottom. And then his ex, and their child, come to visit him in a colorful, distinctive location on a major holiday, at the same time as a major attack by terroristic forces. The ex and the child are taken hostage, with many others, by the nasty masked terrorists. But the man is an expert in violence, and he will save everyone and defeat the terrorists to show his manly superiority.

Yes, Ricky Rouse Has a Gun reads a lot like a treatment for a Die Hard knockoff, though the offhanded apoliticism of the terrorists reads a bit anachronistically in the post-9/11 world. This book could make a very popular, exciting movie, and maybe it will someday.

reads a lot like a treatment for a Die Hard knockoff, though the offhanded apoliticism of the terrorists reads a bit anachronistically in the post-9/11 world. This book could make a very popular, exciting movie, and maybe it will someday.

For now, though, it's a book: written by British writer/producer/director (for film, games, and mostly stage) Jorg Tittel and drawn by London artist/illustrator John Aggs in a neo-'80s style full of flat colors and angular faces. (I do wonder about the gestation period for this book, or if it was conceived in a throwback style: there's something inherently late-'80s or early-'90s about it, in its macho posturing and moral story beats, for all of the specific details that place it in the present day.)

Richard Rouse is that tough man: he walked away from his unit in Afghanistan after getting a "Dear John" letter from his wife/girlfriend and into dead-end jobs in China. But the failure of one of those jobs sends him to a new one at the Fengxian Amusement Park, made up entirely of rip-offs of popular western characters and rides. The proprietor of the park has made a weird Mickey Mouse parody suit, and the American -- Ricky Rouse, yes?, say it in a Charlie Chan accent -- gets a new job in the suit.

And then those terrorists attack on Christmas Day, when the ex and the daughter (and the ex's new rich boyfriend, because there always must be a rich and attractive and powerful new boyfriend) and trapped with the hostages. But Ricky is on the outside. And Ricky, as the title suggests, has a gun of his own.

You know what happens from there. Tittel has some mildly satiric points to make, but this is mostly an action movie on paper: a masked villain will always be someone surprising, and the ethnic sidekick will be injured but make it through, and the ex will discover the hero's true abilities and power. It may not be quite as highbrow as it wants you to believe, but Ricky Rouse Has a Gun is a lot of bloody fun.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Yes, Ricky Rouse Has a Gun

For now, though, it's a book: written by British writer/producer/director (for film, games, and mostly stage) Jorg Tittel and drawn by London artist/illustrator John Aggs in a neo-'80s style full of flat colors and angular faces. (I do wonder about the gestation period for this book, or if it was conceived in a throwback style: there's something inherently late-'80s or early-'90s about it, in its macho posturing and moral story beats, for all of the specific details that place it in the present day.)

Richard Rouse is that tough man: he walked away from his unit in Afghanistan after getting a "Dear John" letter from his wife/girlfriend and into dead-end jobs in China. But the failure of one of those jobs sends him to a new one at the Fengxian Amusement Park, made up entirely of rip-offs of popular western characters and rides. The proprietor of the park has made a weird Mickey Mouse parody suit, and the American -- Ricky Rouse, yes?, say it in a Charlie Chan accent -- gets a new job in the suit.

And then those terrorists attack on Christmas Day, when the ex and the daughter (and the ex's new rich boyfriend, because there always must be a rich and attractive and powerful new boyfriend) and trapped with the hostages. But Ricky is on the outside. And Ricky, as the title suggests, has a gun of his own.

You know what happens from there. Tittel has some mildly satiric points to make, but this is mostly an action movie on paper: a masked villain will always be someone surprising, and the ethnic sidekick will be injured but make it through, and the ex will discover the hero's true abilities and power. It may not be quite as highbrow as it wants you to believe, but Ricky Rouse Has a Gun is a lot of bloody fun.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Reviewing the Mail: Week of 12/27

Welcome to the last "Reviewing the Mail" post of this year, covering the books that arrived Christmas week at my small home in riverine New Jersey. I haven't read these particular editions since the books arrived, but here's what I can tell you about them anyway:

The George R.R. Martin-edited Wild Cards was one of the earlier shared-worlds series -- I think Thieves' World kicked it all off, but Wild Cards was only a little behind -- and has been running, with some stops and starts, for over twenty-five years. But most of the older books in the series have been out of print for most of that time; reprinting efforts have never managed to get beyond the first half-dozen titles. But there's another effort underway now, and it's hit the fourth book: Aces Abroad is coming as a Tor trade paperback on January 13. It has the original eleven stories from the 1988 edition -- by Martin, John J. Miller, Lewis Shiner, Stephen Leigh, Edward Bryant, and others -- plus two new stories by Kevin Andrew Murphy and Carrie Vaughan.

is coming as a Tor trade paperback on January 13. It has the original eleven stories from the 1988 edition -- by Martin, John J. Miller, Lewis Shiner, Stephen Leigh, Edward Bryant, and others -- plus two new stories by Kevin Andrew Murphy and Carrie Vaughan.

And I also have two manga volumes coming out from Vertical this month: first up is Ajin: Demi-Human, Vol. 2 by Gamon Sakurai. It continues the story of the "demi-humans," who keep coming back when they're killed and thus -- because this is comics, and so drama is the most important thing -- have been declared to be not human and thus fair game to be killed as often as anyone wants. Our hero is the requisite callow young man

by Gamon Sakurai. It continues the story of the "demi-humans," who keep coming back when they're killed and thus -- because this is comics, and so drama is the most important thing -- have been declared to be not human and thus fair game to be killed as often as anyone wants. Our hero is the requisite callow young man

The other book I have from Vertical is Tsutomu Nihei's Knights of Sidonia, Vol. 12

The other book I have from Vertical is Tsutomu Nihei's Knights of Sidonia, Vol. 12 , in which the remnants of humanity are crammed into one giant ship, pursued by creepily organic space-monsters, fighting back in big mecha-suits, and searching for somewhere new to live. I looked at the first volume in a round-up post last year.

, in which the remnants of humanity are crammed into one giant ship, pursued by creepily organic space-monsters, fighting back in big mecha-suits, and searching for somewhere new to live. I looked at the first volume in a round-up post last year.

The George R.R. Martin-edited Wild Cards was one of the earlier shared-worlds series -- I think Thieves' World kicked it all off, but Wild Cards was only a little behind -- and has been running, with some stops and starts, for over twenty-five years. But most of the older books in the series have been out of print for most of that time; reprinting efforts have never managed to get beyond the first half-dozen titles. But there's another effort underway now, and it's hit the fourth book: Aces Abroad

And I also have two manga volumes coming out from Vertical this month: first up is Ajin: Demi-Human, Vol. 2

The other book I have from Vertical is Tsutomu Nihei's Knights of Sidonia, Vol. 12

The other book I have from Vertical is Tsutomu Nihei's Knights of Sidonia, Vol. 12Sunday, December 28, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #362: Satellite Sam, Vol. 1 by Fraction & Chaykin

If you want a comic with a lot of leggy blondes in gartered stockings -- the long-haired blondes are friendly; the short-haired ones are man-eating villains -- then you want to look for the Howard Chaykin seal. His work has been amazingly thematically consistent for the last roughly three decades, all men in double-breasted suits, the aforementioned pneumatic women in merry widows and more exotic lingerie, and cross-talk dialogue among a huge cast that it's difficult to keep straight.

He's written his own comics for a long time now -- done it well since at least American Flagg! back in the early 1980s -- so it's surprising to see him doing almost exactly the same thing with a collaborator for the words. That collaborator is no slouch, either: Matt Fraction is a smart and in-demand writer, known for Hawkeye and Sex Criminals among others.

But, from the evidence of the first five issues -- it's not a complete story, which I'll get into more later -- Fraction is channeling Chaykin here, or maybe just writing the things Chaykin likes to draw, as Chaykin does for himself. Satellite Sam is a murder-mystery set in 1951 New York, in the fledgling TV industry, where the star of the eponymous show has just been murdered at the worst time: right before one of the daily shows at 3:45. His lookalike son Mike -- yet another Chaykin trademark -- steps into the role, and up as our more-or-less central hero, but Satellite Sam is an ensemble book, about all of the crew and cast of the show and their various secrets and schemes.

Satellite Sam, Vol. 1: The Lonesome Death of Satellite Sam introduces that cast, and starts to move them around and reveal their secrets, but there's a lot of people and a lot of secrets, so that will take a while. There are secretly gay men, and other sex scandals -- the dead TV hero has a Bob Crane-esque hobby of taking pictures of his many female conquests in cheap lingerie (because Chaykin) -- and I'd bet serious cash that at least one character will turn out to be secretly or formerly a member of a Communist party, since this is 1951. There's already one character who will likely turn into a fictional version of Ernie Kovacs, and -- again, because of Chaykin -- quite a lot of tastefully depicted oral sex in various permutations.

introduces that cast, and starts to move them around and reveal their secrets, but there's a lot of people and a lot of secrets, so that will take a while. There are secretly gay men, and other sex scandals -- the dead TV hero has a Bob Crane-esque hobby of taking pictures of his many female conquests in cheap lingerie (because Chaykin) -- and I'd bet serious cash that at least one character will turn out to be secretly or formerly a member of a Communist party, since this is 1951. There's already one character who will likely turn into a fictional version of Ernie Kovacs, and -- again, because of Chaykin -- quite a lot of tastefully depicted oral sex in various permutations.

There's nothing particularly new here: it's historical fiction in a well-known recent period, hitting all of the beats that we expect. But it's entertaining, as long as you can keep the characters straight, and Chaykin does draw gorgeous women in long stockings and very little else. Satellite Sam's strengths may be very specific, but they're definitely there.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

He's written his own comics for a long time now -- done it well since at least American Flagg! back in the early 1980s -- so it's surprising to see him doing almost exactly the same thing with a collaborator for the words. That collaborator is no slouch, either: Matt Fraction is a smart and in-demand writer, known for Hawkeye and Sex Criminals among others.

But, from the evidence of the first five issues -- it's not a complete story, which I'll get into more later -- Fraction is channeling Chaykin here, or maybe just writing the things Chaykin likes to draw, as Chaykin does for himself. Satellite Sam is a murder-mystery set in 1951 New York, in the fledgling TV industry, where the star of the eponymous show has just been murdered at the worst time: right before one of the daily shows at 3:45. His lookalike son Mike -- yet another Chaykin trademark -- steps into the role, and up as our more-or-less central hero, but Satellite Sam is an ensemble book, about all of the crew and cast of the show and their various secrets and schemes.

Satellite Sam, Vol. 1: The Lonesome Death of Satellite Sam

There's nothing particularly new here: it's historical fiction in a well-known recent period, hitting all of the beats that we expect. But it's entertaining, as long as you can keep the characters straight, and Chaykin does draw gorgeous women in long stockings and very little else. Satellite Sam's strengths may be very specific, but they're definitely there.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Saturday, December 27, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #361: Ms. Marvel, Vol. 1 by Wilson & Alphona

Originality is a sliding scale: it depends entirely on context. In the world of fine art, after a century of conceptual and site-specific and performance and found, it would take a whole lot to be original. In superhero comics, though, a Muslim teenager with the powers of Elongated Man is a blazingly new concept.

I pick on the new Ms. Marvel, but it's true: superhero comics are so regimented and defined that just having a main character who isn't a straight white male between the ages of 16 and 35 is shocking to large segments of the audience. The new Ms. Marvel series has gotten generally positive reviews, but those are all from people already inclined to want diverse characters in standard spandex outfits punching the same old villains in the same old ways. And that audience gets praised for their forward-thinking ways far too much, to my mind, since they're only forward-thinking in the most narrow, blindered ways: they only want a wider variety of people on the covers of their punching-the-world-better comics.

Kamala Khan is a young person who suddenly gets powers and feels the urge to better the world with them; she comes into conflict with her family's expectations for her and with unpleasant schoolmates whom she saves despite their unpleasantness. She's awkward with her powers and hero-worships longer-established heroes, and is deeply earnest and entirely a positive role model.

In other words, she's Peter Parker, and a half-dozen other similar heroes from the past fifty years in the same vein. Sure, she's female, from Jersey City rather than Brooklyn, vaguely Muslim rather than vaguely Christian, and Pakistani rather than unspecified WASP, but those are all pretty superficial details over the same story framework.

Ms. Marvel, Vol. 1: No Normal collects the first five issues of Kamala's ongoing series, plus an eight-page story from an anthology title -- all written by G. Willow Wilson (who has the great benefit in this context of being a Muslim woman as well as an award-winning writer) and drawn by Adrian Alphona (best known for the cult favorite Runaways series). It's relatively smart, self-aware superhero stuff: origin, working out the details of the powers (stretching and shrinking, changing to look like other people, general stretchy powers that don't yet rise to the level of Plastic Man deformity), and the first confrontation with the goons of her very first supervillain. It is a bit quirky, driven by Alphona's semi-indy drawings and Ian Herring's soft colors, with a look more like Omega the Unknown than Marvel-standard. (Though the cover, interestingly, is Marvel-standard rather than Alphona/Herring, showing that comics still want to make everything look the same as much as possible.)

collects the first five issues of Kamala's ongoing series, plus an eight-page story from an anthology title -- all written by G. Willow Wilson (who has the great benefit in this context of being a Muslim woman as well as an award-winning writer) and drawn by Adrian Alphona (best known for the cult favorite Runaways series). It's relatively smart, self-aware superhero stuff: origin, working out the details of the powers (stretching and shrinking, changing to look like other people, general stretchy powers that don't yet rise to the level of Plastic Man deformity), and the first confrontation with the goons of her very first supervillain. It is a bit quirky, driven by Alphona's semi-indy drawings and Ian Herring's soft colors, with a look more like Omega the Unknown than Marvel-standard. (Though the cover, interestingly, is Marvel-standard rather than Alphona/Herring, showing that comics still want to make everything look the same as much as possible.)

It's not nearly as different or amazing as some sectors of the Internet would lead you to believe; it's a superhero comic from Marvel, and hits all of the expected story beats. But it's an appealing slab of superhero comics, and, at least this far in, isn't tied up with continuity and event knots that damage so many of it's shelf-mates. You could do worse than to read this, but you could also do vastly better.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

I pick on the new Ms. Marvel, but it's true: superhero comics are so regimented and defined that just having a main character who isn't a straight white male between the ages of 16 and 35 is shocking to large segments of the audience. The new Ms. Marvel series has gotten generally positive reviews, but those are all from people already inclined to want diverse characters in standard spandex outfits punching the same old villains in the same old ways. And that audience gets praised for their forward-thinking ways far too much, to my mind, since they're only forward-thinking in the most narrow, blindered ways: they only want a wider variety of people on the covers of their punching-the-world-better comics.

Kamala Khan is a young person who suddenly gets powers and feels the urge to better the world with them; she comes into conflict with her family's expectations for her and with unpleasant schoolmates whom she saves despite their unpleasantness. She's awkward with her powers and hero-worships longer-established heroes, and is deeply earnest and entirely a positive role model.

In other words, she's Peter Parker, and a half-dozen other similar heroes from the past fifty years in the same vein. Sure, she's female, from Jersey City rather than Brooklyn, vaguely Muslim rather than vaguely Christian, and Pakistani rather than unspecified WASP, but those are all pretty superficial details over the same story framework.

Ms. Marvel, Vol. 1: No Normal

It's not nearly as different or amazing as some sectors of the Internet would lead you to believe; it's a superhero comic from Marvel, and hits all of the expected story beats. But it's an appealing slab of superhero comics, and, at least this far in, isn't tied up with continuity and event knots that damage so many of it's shelf-mates. You could do worse than to read this, but you could also do vastly better.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Friday, December 26, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #360: The Motherless Oven by Rob Davis

When a work of art depicts a particularly strange world, there's a natural impulse to focus on that world and its strangeness -- it's what rich and unique and special about that work, and an easy way in.

So most reviews of Rob Davis's graphic novel The Motherless Oven have focused on the very odd world he's constructed: an alternate British youth society where kids build their parents (various contraptions, useful or not), where it rains knives, where everyone knows their deathday, and where small gods embodied in mechanical objects are part of everyday life. But Motherless Oven is just set in that world; it's at its core a fatalistic story about growing up and pushing limits, about finding out the truth and trying to escape your fate. The strangeness of the world allows those more important aspects to work -- the audience doesn't know where the limits are, what growing up means in this world, what the truth could possibly be, and whether fate can be escaped.

have focused on the very odd world he's constructed: an alternate British youth society where kids build their parents (various contraptions, useful or not), where it rains knives, where everyone knows their deathday, and where small gods embodied in mechanical objects are part of everyday life. But Motherless Oven is just set in that world; it's at its core a fatalistic story about growing up and pushing limits, about finding out the truth and trying to escape your fate. The strangeness of the world allows those more important aspects to work -- the audience doesn't know where the limits are, what growing up means in this world, what the truth could possibly be, and whether fate can be escaped.

Motherless Oven opens on a rainy Wednesday afternoon; Scarper Lee is home, basically alone -- his mum is hiding from the rain in the cupboard under the stairs and he had to chain his father in the shed to prevent the old man (read: wind-powered brass assemblage with huge golden sails) roaming. Scarper doesn't much like people, so this is fine: as much as he likes anything, he likes hearing the clatter of the knives hitting the houses and ground. But there's a knock at the door: his new classmate Vera Pike is there.

It's never quite clear exactly why Vera takes such an interest in Scarper: he's gloomy and quiet and grumpy, and never good company. Perhaps it's the challenge she's after, or more likely she's wanted a big adventure for a while, and Scarper gives her the best opportunity. Because Scarper's deathday is only three weeks away: he'll die on another Wednesday, very soon.

Scarper doesn't like Vera, because she's confidently different and pushy and asks questions nobody can answer and calls attention to herself (and incidentally to him). But she won't leave him alone, and soon she's gathered another sad case: Castro Smith, who has Medicated Inference Syndrome and whose perceptions of the world are controlled by a dial on his chest.

Vera leads the two boys on an escape from school to find the legendary Motherless Oven, the place where children supposedly are born and craft their parents. (No one ever remembers making their parents, though everyone is completely sure that they did so.) They mostly travel through British suburbia: row houses, high streets, a few open plots of ground. And behind them are the police: hard-faced old couples in slow clockwork carriages, as relentless as old-school zombies and nearly as deadly.

Scarper and Vera and Castro travel far and see many things, but I can't tell you if Scarper escapes his deathday or if the Motherless Oven is what they were expecting. This is a brilliantly imaginative story with a unique world, filled with details both of worldbuilding and character and with a powerful ending. You need to read it for yourself.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

So most reviews of Rob Davis's graphic novel The Motherless Oven

Motherless Oven opens on a rainy Wednesday afternoon; Scarper Lee is home, basically alone -- his mum is hiding from the rain in the cupboard under the stairs and he had to chain his father in the shed to prevent the old man (read: wind-powered brass assemblage with huge golden sails) roaming. Scarper doesn't much like people, so this is fine: as much as he likes anything, he likes hearing the clatter of the knives hitting the houses and ground. But there's a knock at the door: his new classmate Vera Pike is there.

It's never quite clear exactly why Vera takes such an interest in Scarper: he's gloomy and quiet and grumpy, and never good company. Perhaps it's the challenge she's after, or more likely she's wanted a big adventure for a while, and Scarper gives her the best opportunity. Because Scarper's deathday is only three weeks away: he'll die on another Wednesday, very soon.

Scarper doesn't like Vera, because she's confidently different and pushy and asks questions nobody can answer and calls attention to herself (and incidentally to him). But she won't leave him alone, and soon she's gathered another sad case: Castro Smith, who has Medicated Inference Syndrome and whose perceptions of the world are controlled by a dial on his chest.

Vera leads the two boys on an escape from school to find the legendary Motherless Oven, the place where children supposedly are born and craft their parents. (No one ever remembers making their parents, though everyone is completely sure that they did so.) They mostly travel through British suburbia: row houses, high streets, a few open plots of ground. And behind them are the police: hard-faced old couples in slow clockwork carriages, as relentless as old-school zombies and nearly as deadly.

Scarper and Vera and Castro travel far and see many things, but I can't tell you if Scarper escapes his deathday or if the Motherless Oven is what they were expecting. This is a brilliantly imaginative story with a unique world, filled with details both of worldbuilding and character and with a powerful ending. You need to read it for yourself.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Thursday, December 25, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #359: Bumf, Vol. 1 by Joe Sacco

Physical laws don't usually apply to literary careers. There's no reason to ever expect them to do so. But, once in a while, it's the only way to explain an otherwise inexplicable change.

For every action, there's an equal and opposite reaction.

Joe Sacco has spent the last twenty-five years -- nearly his entire career in comics -- carefully documenting real events and putting them down on paper, studying sources and interviewing hundreds of people to get as close to the precise truth of events as he possibly can. Throughout that time, he's been drawn to wars and conflict: Palestine, the wars that tore apart Yugoslavia, The Great War. He's been sober, balanced, careful, serious, as close to unbiased as he could get.

But, clearly, there was another Joe Sacco inside, yearning to break out. The shadow Sacco was the opposite of all of those things: wild, anarchic, accusatory, phantasmagorical, profane, angry, demanding, and itching to turn real-world concerns into a fabulistic, metaphorical, bizarre story. And that Sacco burst forth this year, with a 120-page screed against war, torture, ubiquitous surveillance, drone strikes, the Obama administration, and anything else he can aim at, under the title Bumf, Vol. 1 . (Online, the book carries the subtitle I Buggered the Kaiser, but the book itself doesn't anywhere declare that to be its title -- it is the title of one of the stories/sections inside, though.)

. (Online, the book carries the subtitle I Buggered the Kaiser, but the book itself doesn't anywhere declare that to be its title -- it is the title of one of the stories/sections inside, though.)

Bumf is explicitly in the tone and style of the old underground comics; Sacco wants to draw direct parallels between the US of Vietnam and the US of Iraq/Afghanistan, and between Richard Nixon and Barack Obama. (As you can see from the cover, one of his main characters is Obama drawn as Nixon.) Sacco himself is another character, as he has been in his nonfiction comics, and he's as secondary and peripheral here as he was in those stories: Sacco-the-character is there to chronicle and publicize, but he doesn't do things.

Sacco uses complex shifting metaphors -- which is probably too fancy a way of saying he's screwing around with ideas and visuals around these things that are obsessing and infuriating him -- around wars and drones and surveillance and torture, until, in the late pages of Bumf, he's drawing huge groupings of people, all naked except for sacks or eyeless headsman's hoods, involved in horrific acts offhandedly or almost gleefully. Like the undergrounds, it's all held together mostly by Sacco's insistence that it does hold together -- it's nearly stream of consciousness, with characters who are signposts for ideas and roles rather than people, and leaps from one audacity to another. (Though none of those audacities, pointedly, offer any hope.)

Sacco dates each of his pages, so the reader can see that the first twenty-one pages dribbled out between 2004 and late 2010; this story has been long gestating. But the bulk of the book was drawn between March 2013 and May 2014: something triggered Sacco to dive into this stew of profanity and anger and push it forward quickly.

Bumf is one long scream of impotent rage and frustrated hope, full of sex and violence and the mixture of the two -- all pushed into the background by Sacco's alternate-world version of the numbing bureaucrat-speak that justified all of those same things in the real world. It's not a book for anyone happy with the current situation, as Zap wasn't for anyone happy with the Vietnam War. But it's an amazing imaginative achievement, and very unlike anything we've seen from Sacco since very early in his career.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

For every action, there's an equal and opposite reaction.

Joe Sacco has spent the last twenty-five years -- nearly his entire career in comics -- carefully documenting real events and putting them down on paper, studying sources and interviewing hundreds of people to get as close to the precise truth of events as he possibly can. Throughout that time, he's been drawn to wars and conflict: Palestine, the wars that tore apart Yugoslavia, The Great War. He's been sober, balanced, careful, serious, as close to unbiased as he could get.

But, clearly, there was another Joe Sacco inside, yearning to break out. The shadow Sacco was the opposite of all of those things: wild, anarchic, accusatory, phantasmagorical, profane, angry, demanding, and itching to turn real-world concerns into a fabulistic, metaphorical, bizarre story. And that Sacco burst forth this year, with a 120-page screed against war, torture, ubiquitous surveillance, drone strikes, the Obama administration, and anything else he can aim at, under the title Bumf, Vol. 1

Bumf is explicitly in the tone and style of the old underground comics; Sacco wants to draw direct parallels between the US of Vietnam and the US of Iraq/Afghanistan, and between Richard Nixon and Barack Obama. (As you can see from the cover, one of his main characters is Obama drawn as Nixon.) Sacco himself is another character, as he has been in his nonfiction comics, and he's as secondary and peripheral here as he was in those stories: Sacco-the-character is there to chronicle and publicize, but he doesn't do things.

Sacco uses complex shifting metaphors -- which is probably too fancy a way of saying he's screwing around with ideas and visuals around these things that are obsessing and infuriating him -- around wars and drones and surveillance and torture, until, in the late pages of Bumf, he's drawing huge groupings of people, all naked except for sacks or eyeless headsman's hoods, involved in horrific acts offhandedly or almost gleefully. Like the undergrounds, it's all held together mostly by Sacco's insistence that it does hold together -- it's nearly stream of consciousness, with characters who are signposts for ideas and roles rather than people, and leaps from one audacity to another. (Though none of those audacities, pointedly, offer any hope.)

Sacco dates each of his pages, so the reader can see that the first twenty-one pages dribbled out between 2004 and late 2010; this story has been long gestating. But the bulk of the book was drawn between March 2013 and May 2014: something triggered Sacco to dive into this stew of profanity and anger and push it forward quickly.

Bumf is one long scream of impotent rage and frustrated hope, full of sex and violence and the mixture of the two -- all pushed into the background by Sacco's alternate-world version of the numbing bureaucrat-speak that justified all of those same things in the real world. It's not a book for anyone happy with the current situation, as Zap wasn't for anyone happy with the Vietnam War. But it's an amazing imaginative achievement, and very unlike anything we've seen from Sacco since very early in his career.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Wednesday, December 24, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #358: Weapons of Mass Diplomacy by Lanzac and Blain

It's good to be sober and adult and serious, to think about consequences and weigh possibilities, to consider options and use caution. But, sometimes, that's not enough. Sometimes, everyone else is in a frenzy to be petty and violent and destructive, and the "serious adults" are dragged along behind, trying to make a slight delay or a minor change of wording into a moral victory.

Weapons of Mass Diplomacy is one of those stories, though it won't tell you that directly: you need to know the real history to pierce the thin veil of fiction cloaking this graphic novel. It's the story of a young writer, Arthur Vlaminck, who goes to work for the French Foreign Minister, Alexandre Taillard de Vorms, in the tumultuous year 2002, and gets caught up in an international crisis about the Kingdom of Khemed, terrorism, and purported weapons of mass destruction.

is one of those stories, though it won't tell you that directly: you need to know the real history to pierce the thin veil of fiction cloaking this graphic novel. It's the story of a young writer, Arthur Vlaminck, who goes to work for the French Foreign Minister, Alexandre Taillard de Vorms, in the tumultuous year 2002, and gets caught up in an international crisis about the Kingdom of Khemed, terrorism, and purported weapons of mass destruction.

Nearly all of the players appear here in masks -- de Vorms was in real life Dominique de Villepin, for whom Weapons writer Abel Lanzac (under his real name, Antonin Baudry) worked as a speechwriter in the actual 2002. Khemed is of course Iraq. Even Weapons has a new name in English; the original French version was named Quai d'Orsay, after the eponymous home of the Foreign Ministry -- a name as clear in France as a book called Pennsylvania Avenue would be here. Only one person appears here under his real name: Weapons' artist, Christophe Blain. (Though many nations -- France, the USA, Germany, Syria, etc. -- are called by their true names.)

Weapons collects what was two French albums: two hundred pages of dense comics, full of long speeches and frenzied activity, as de Vorms's staff runs from one crisis to the next. (It's a bit like The Thick of It, but with less cursing.) Vlaminck is our viewpoint, but the charismatic and energizing de Vorms is the central character: all activity circles around him, and his shifting demands and stances drive Vlaminck and the rest of his staff to ever-greater efforts.

But we know this was all useless. "Khemed" was invaded, by the USA with some hangers-on to make a "coalition of the willing." There were no weapons of mass destruction. There was no connection to international terrorism. There were no crowds meeting the foreign troops as liberators. And, most importantly, there was no peace, only a grinding, horrible guerrilla war that still goes on a dozen years later. Diplomacy failed entirely; all of de Vorms's work was worthless.

France has played only a small part in that war: in real life, as in Weapons, they tried to be the sensible adults and were ruthlessly attacked by American fools and charlatans for their reward. So this is yet another story of a campaign that failed: valiantly fought, certainly, but completely lost.

Amazingly, Lanzac and Blain keep it amusing and quick throughout, even with big pages full of panels and long dialogue stretches filled with polysyllabic words -- Blain is a master of body language as always, and his people are heavily caricatured but still human, all huge noses and beetling brows. Weapons is even funny a lot of the time, as with the dramatic DOOM sound effect every time de Vorms enters a room.

This is a big book for serious adults who nevertheless have a sense of humor and proportion -- who know what really happened but can still avoid despair, who want to believe that diplomacy can still work and that getting the words just right is an excellent use of time. I want to believe that is a lot of people; I want to believe that's most of us.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Weapons of Mass Diplomacy

Nearly all of the players appear here in masks -- de Vorms was in real life Dominique de Villepin, for whom Weapons writer Abel Lanzac (under his real name, Antonin Baudry) worked as a speechwriter in the actual 2002. Khemed is of course Iraq. Even Weapons has a new name in English; the original French version was named Quai d'Orsay, after the eponymous home of the Foreign Ministry -- a name as clear in France as a book called Pennsylvania Avenue would be here. Only one person appears here under his real name: Weapons' artist, Christophe Blain. (Though many nations -- France, the USA, Germany, Syria, etc. -- are called by their true names.)

Weapons collects what was two French albums: two hundred pages of dense comics, full of long speeches and frenzied activity, as de Vorms's staff runs from one crisis to the next. (It's a bit like The Thick of It, but with less cursing.) Vlaminck is our viewpoint, but the charismatic and energizing de Vorms is the central character: all activity circles around him, and his shifting demands and stances drive Vlaminck and the rest of his staff to ever-greater efforts.

But we know this was all useless. "Khemed" was invaded, by the USA with some hangers-on to make a "coalition of the willing." There were no weapons of mass destruction. There was no connection to international terrorism. There were no crowds meeting the foreign troops as liberators. And, most importantly, there was no peace, only a grinding, horrible guerrilla war that still goes on a dozen years later. Diplomacy failed entirely; all of de Vorms's work was worthless.

France has played only a small part in that war: in real life, as in Weapons, they tried to be the sensible adults and were ruthlessly attacked by American fools and charlatans for their reward. So this is yet another story of a campaign that failed: valiantly fought, certainly, but completely lost.

Amazingly, Lanzac and Blain keep it amusing and quick throughout, even with big pages full of panels and long dialogue stretches filled with polysyllabic words -- Blain is a master of body language as always, and his people are heavily caricatured but still human, all huge noses and beetling brows. Weapons is even funny a lot of the time, as with the dramatic DOOM sound effect every time de Vorms enters a room.

This is a big book for serious adults who nevertheless have a sense of humor and proportion -- who know what really happened but can still avoid despair, who want to believe that diplomacy can still work and that getting the words just right is an excellent use of time. I want to believe that is a lot of people; I want to believe that's most of us.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Tuesday, December 23, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #357: Sugar Skull by Charles Burns

When a trilogy is finally finished, the first question is "how's the ending?" And so we're here, having made it through X'ed Out and The Hive, ready to finally know what happened to Doug in the real world and Johnny/Nit-Nit in the strange world, and wanting to find out if it all makes sense and if it's all worth it.

It definitely does all make sense in Sugar Skull , Charles Burns's end to the trio of graphic novels that very weirdly play homage to Tintin. Whether it's all worth it will be more a matter of personal opinion: some of the answers have to be assumed or derived from what we see, but all of those answers tend to be deflating.

, Charles Burns's end to the trio of graphic novels that very weirdly play homage to Tintin. Whether it's all worth it will be more a matter of personal opinion: some of the answers have to be assumed or derived from what we see, but all of those answers tend to be deflating.

Doug has been passive and unhappy for three books now, obsessed with a failed relationship with Sarah and his own many failures. Johnny is almost as passive, but with a flatter adventure-story affect, as he wanders through the strange world he finds himself in, full of odd creatures and body-horror. We have assumed they were the same person for three books now, that Johnny's story was a vision or dream or other experience of Doug's. The exact connection is still not explicit -- is Johnny's world one Doug retreats to continuously, or did the entire Johnny-story happen at once, after the event that sent Doug running to his father's house just before the beginning of X'ed Out? -- but all of the outlines are clear.

And none of it reflects well on Doug. Burns's post-RAW work has mostly focused on weak, passive young men -- both Black Hole and this trilogy -- but Doug is here revealed as a Platonic sad sack, working on what we assume is really bad "art," being a whiny annoying drunk, and morose about the death six years before of the father he didn't even like. There's nothing wrong with stories about characters like that, but the modern American comics field is a particularly infertile ground for them, and so Doug stands that much further out for being that pathetic and miserable.

The big explanation in Sugar Skull works, and explains well everything we've seen in the first two books. But it's an entirely real-world explanation, and, like so many other plot developments, it shows Doug once again to be weak, whiny, and acted upon. That's who he is, clearly, but many readers, lured in by that Tintin connection, have wanted at least a touch of heroism or selflessness or at the bare minimum compassion. Charles Burns will not provide that: not in this trilogy, and very rarely in any of his other works. And, this time out, he's not providing that deep frisson of horror that's been a hallmark of his previous stories, either: the secrets have all to do with Doug and the real world.

Sugar Skull, then, is a bit disappointing: we didn't expect exaltation, but we hoped for something creepy and mysterious. There are creeps and mysteries in this trilogy, true, but they're not central to Doug's story.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

It definitely does all make sense in Sugar Skull

Doug has been passive and unhappy for three books now, obsessed with a failed relationship with Sarah and his own many failures. Johnny is almost as passive, but with a flatter adventure-story affect, as he wanders through the strange world he finds himself in, full of odd creatures and body-horror. We have assumed they were the same person for three books now, that Johnny's story was a vision or dream or other experience of Doug's. The exact connection is still not explicit -- is Johnny's world one Doug retreats to continuously, or did the entire Johnny-story happen at once, after the event that sent Doug running to his father's house just before the beginning of X'ed Out? -- but all of the outlines are clear.

And none of it reflects well on Doug. Burns's post-RAW work has mostly focused on weak, passive young men -- both Black Hole and this trilogy -- but Doug is here revealed as a Platonic sad sack, working on what we assume is really bad "art," being a whiny annoying drunk, and morose about the death six years before of the father he didn't even like. There's nothing wrong with stories about characters like that, but the modern American comics field is a particularly infertile ground for them, and so Doug stands that much further out for being that pathetic and miserable.

The big explanation in Sugar Skull works, and explains well everything we've seen in the first two books. But it's an entirely real-world explanation, and, like so many other plot developments, it shows Doug once again to be weak, whiny, and acted upon. That's who he is, clearly, but many readers, lured in by that Tintin connection, have wanted at least a touch of heroism or selflessness or at the bare minimum compassion. Charles Burns will not provide that: not in this trilogy, and very rarely in any of his other works. And, this time out, he's not providing that deep frisson of horror that's been a hallmark of his previous stories, either: the secrets have all to do with Doug and the real world.

Sugar Skull, then, is a bit disappointing: we didn't expect exaltation, but we hoped for something creepy and mysterious. There are creeps and mysteries in this trilogy, true, but they're not central to Doug's story.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Monday, December 22, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #356: The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil by Stephen Collins

Evil is such a loaded word. Axis of Evil, Evil Empire, Doctor Evil. Most of the time, what it really means is "those guys on the other side of this current battle" -- it's a way to keep the lines clear between Us and Them. Everybody is somebody's Ultimate Evil, somebody's Great Satan.

Stephen Collins clearly knows that: his first graphic novel The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil is a fable or metaphor about evil and conformity and groupthink and what it means to be good -- when good means "just like everyone else."

is a fable or metaphor about evil and conformity and groupthink and what it means to be good -- when good means "just like everyone else."

The metaphor may be even more pointed when you remember Collins is British: there's an island named Here, where everyone lives in peace and harmony, and does their best to ignore the turbulent Sea all around Here, and even more resolutely ignores the existence of anywhere else in the world, known only as There. Here is happy and stable and ordered; There is strange and different and chaotic. Here is tidy -- a very British word for a very British idea, which is the core of the metaphor here.

One day, untidiness comes to Here. One man named Dave -- previously entirely tidy and happy in his society, bald but for eyebrows and one tiny hair on his upper lip -- begins growing a beard. Well, that's the wrong way to put it: it sounds like there's an element of choice or agency. The beard grows. Dave is just there when it happens. It grows unstoppably, uncontrollably, without limits, faster than it can be cut or trimmed or shaped. All of the forces of tidiness are brought to bear on the beard, and in Here, those are very powerful forces. But the beard cannot be tamed or tidied or controlled, only just barely guided. And, in the end, there is only one choice that a tidy land can make when faced with such gigantic untidiness.

Collins tells this story in quiet, careful words that often turn poetic -- Dave's story begins "Beneath the skin/of everything/is something nobody can know. The job of the skin/is to keep it all in/and never let anything show." And he tells it in soft pencil-y art, filled with careful crosshatching and tones, making a world of soft hominess invaded by the inky black horns and spikes of that beard. The combination is assured and pointed, deeply embodying its metaphor and pushing it forward in several directions at once, examining all of the aspects of tidiness and disorder.

Most importantly, The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil entirely lives up to both its title and its great cover: it's a searching, inquisitive book with something to say for every one of us -- the tidy and untidy alike.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Stephen Collins clearly knows that: his first graphic novel The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil

The metaphor may be even more pointed when you remember Collins is British: there's an island named Here, where everyone lives in peace and harmony, and does their best to ignore the turbulent Sea all around Here, and even more resolutely ignores the existence of anywhere else in the world, known only as There. Here is happy and stable and ordered; There is strange and different and chaotic. Here is tidy -- a very British word for a very British idea, which is the core of the metaphor here.

One day, untidiness comes to Here. One man named Dave -- previously entirely tidy and happy in his society, bald but for eyebrows and one tiny hair on his upper lip -- begins growing a beard. Well, that's the wrong way to put it: it sounds like there's an element of choice or agency. The beard grows. Dave is just there when it happens. It grows unstoppably, uncontrollably, without limits, faster than it can be cut or trimmed or shaped. All of the forces of tidiness are brought to bear on the beard, and in Here, those are very powerful forces. But the beard cannot be tamed or tidied or controlled, only just barely guided. And, in the end, there is only one choice that a tidy land can make when faced with such gigantic untidiness.

Collins tells this story in quiet, careful words that often turn poetic -- Dave's story begins "Beneath the skin/of everything/is something nobody can know. The job of the skin/is to keep it all in/and never let anything show." And he tells it in soft pencil-y art, filled with careful crosshatching and tones, making a world of soft hominess invaded by the inky black horns and spikes of that beard. The combination is assured and pointed, deeply embodying its metaphor and pushing it forward in several directions at once, examining all of the aspects of tidiness and disorder.

Most importantly, The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil entirely lives up to both its title and its great cover: it's a searching, inquisitive book with something to say for every one of us -- the tidy and untidy alike.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Reviewing the Mail: Week of 12/20

After two weeks of no books in the mail, I was pretty sure this was going to be a quiet month. But a couple of interesting things came in the last few days, so let me explain the ground rules again. I review books, so publicists send me books. And I write about all of those books here every week, since I know I won't get to read and review all of them.

First up is the new novel from Jo Walton, one of the best and most idiosyncratic fantasy writers working today. (To back up that second claim: can you think of anyone else with the range to break in with a historical Arthurian duology, make her name with an alternate history detective triptych, and win a World Fantasy Award for a Trollopian novel about dragons?) From her this time is an equally individual book, The Just City , set in a city out of time created by the goddess Athena to teach thousands of human children from all eras. And into that city comes Athena's brother, the god Apollo, in disguise, at the same time that the famous philosopher Socrates arrives to teach and question. That's certainly not a setting or a plot you'd get from anyone else in the field, and it sounds intriguingly cerebral. The Just City is a Tor hardcover, arriving January 13.

, set in a city out of time created by the goddess Athena to teach thousands of human children from all eras. And into that city comes Athena's brother, the god Apollo, in disguise, at the same time that the famous philosopher Socrates arrives to teach and question. That's certainly not a setting or a plot you'd get from anyone else in the field, and it sounds intriguingly cerebral. The Just City is a Tor hardcover, arriving January 13.

And the other book I have is Foxglove Summer

And the other book I have is Foxglove Summer , the fifth in the "Rivers of London" series by Ben Aaronovitch. police procedurals about England's most junior wizard, Peter Grant. This time out, Peter is sent out to rural Herefordshire to make sure that the mysterious disappearance of two young girls has nothing to do with the supernatural, and stays to help with the investigation even though he's sure there's nothing magical going on. (And I would bet serious coin that he turns out to be wrong about that.) This is a DAW mass market paperback -- cheap! -- and will be hitting your favored bookseller in January.

, the fifth in the "Rivers of London" series by Ben Aaronovitch. police procedurals about England's most junior wizard, Peter Grant. This time out, Peter is sent out to rural Herefordshire to make sure that the mysterious disappearance of two young girls has nothing to do with the supernatural, and stays to help with the investigation even though he's sure there's nothing magical going on. (And I would bet serious coin that he turns out to be wrong about that.) This is a DAW mass market paperback -- cheap! -- and will be hitting your favored bookseller in January.

First up is the new novel from Jo Walton, one of the best and most idiosyncratic fantasy writers working today. (To back up that second claim: can you think of anyone else with the range to break in with a historical Arthurian duology, make her name with an alternate history detective triptych, and win a World Fantasy Award for a Trollopian novel about dragons?) From her this time is an equally individual book, The Just City

And the other book I have is Foxglove Summer

And the other book I have is Foxglove SummerSunday, December 21, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #355: Loverboys by Gilbert Hernandez

Many of Gilbert Hernandez's best stories and most characteristic work are about connections that aren't made, things that don't quite happen, and relationships that drift away until they stop entirely. And he tells those stories quietly, from an omniscient, relentless point of view, that sees everything but doesn't deign to show it all to the reader. That these stories are full of events and characters can mask the fact that the most important events are inside these characters' heads, and Hernandez will never explain those events, or even necessarily let us know when they happen.

So Hernandez's characters rarely tell us their motivation, or show it clearly: we see what they do, and we can guess why, but it will always be a guess. And in his shorter, standalone works, where we don't have a deep well of knowledge of those characters to draw on, that can make things even more enigmatic or disconnected, as we watch people we only barely know do things for reasons we can only speculate about.

Loverboys is that kind of story: it's set in a small town -- probably one of the inland, semi-industrial towns of Southern California, but not necessarily -- but it has a large cast for its eighty pages: about a dozen important people, all of whom have unclear motivations and needs and desires. Hernandez clearly knows this is a large cast for the length of story, since he explains/lampshades it on the first pages, where a girl is asking how many people live in this town. Six hundred and seventy-seven is the answer -- and so Hernandez implies we should see how radically he's simplifying the town to show it to us in only ten or fifteen characters.

is that kind of story: it's set in a small town -- probably one of the inland, semi-industrial towns of Southern California, but not necessarily -- but it has a large cast for its eighty pages: about a dozen important people, all of whom have unclear motivations and needs and desires. Hernandez clearly knows this is a large cast for the length of story, since he explains/lampshades it on the first pages, where a girl is asking how many people live in this town. Six hundred and seventy-seven is the answer -- and so Hernandez implies we should see how radically he's simplifying the town to show it to us in only ten or fifteen characters.

Central to this story is Rocky, an attractive young man who's having affairs with both his female boss and Mrs. Paz, an older woman who was his occasional substitute teacher twenty years before and soon becomes the teacher of his much younger sister Daniela. Mrs. Paz also watches Daniela for the middle of the book, as Rocky takes a long trip, supposedly for business, with that boss. Loverboys is a story about who loves who, and how much, and who doesn't love who, with a little bit of who's having sex with who (though not as much as the cover might imply to readers of Hernandez's old Birdland comic). It all circles around Rocky and Daniela and Mrs. Paz, though Rocky is mostly a cipher or a plot device -- he's always calm and detached, so we don't understand him the way we come to understand Daniela and Mrs. Paz.

Loverboys is quick and not entirely satisfying; it has an enigmatic supernatural element that never came into focus for me and an ending that asserts motivation for several characters -- or, rather, has other characters accuse them of those motivations -- which feels like a rushed attempt at closure. The town of Lagrimas is not Palomar; we don't have hundreds of pages of history with these people. And so they walk on stage, act out this one story, and then leave, still mostly strangers. They are intriguing strangers, certainly, full of life and passion, but they leave so quickly we're left wondering who they really are.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

So Hernandez's characters rarely tell us their motivation, or show it clearly: we see what they do, and we can guess why, but it will always be a guess. And in his shorter, standalone works, where we don't have a deep well of knowledge of those characters to draw on, that can make things even more enigmatic or disconnected, as we watch people we only barely know do things for reasons we can only speculate about.

Loverboys

Central to this story is Rocky, an attractive young man who's having affairs with both his female boss and Mrs. Paz, an older woman who was his occasional substitute teacher twenty years before and soon becomes the teacher of his much younger sister Daniela. Mrs. Paz also watches Daniela for the middle of the book, as Rocky takes a long trip, supposedly for business, with that boss. Loverboys is a story about who loves who, and how much, and who doesn't love who, with a little bit of who's having sex with who (though not as much as the cover might imply to readers of Hernandez's old Birdland comic). It all circles around Rocky and Daniela and Mrs. Paz, though Rocky is mostly a cipher or a plot device -- he's always calm and detached, so we don't understand him the way we come to understand Daniela and Mrs. Paz.

Loverboys is quick and not entirely satisfying; it has an enigmatic supernatural element that never came into focus for me and an ending that asserts motivation for several characters -- or, rather, has other characters accuse them of those motivations -- which feels like a rushed attempt at closure. The town of Lagrimas is not Palomar; we don't have hundreds of pages of history with these people. And so they walk on stage, act out this one story, and then leave, still mostly strangers. They are intriguing strangers, certainly, full of life and passion, but they leave so quickly we're left wondering who they really are.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Saturday, December 20, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #354: The Whispering Skull by Jonathan Stroud

It's not easy work, hunting ghosts. First of all, only some children can even see and hear the ghosts to fight them -- the ability starts to fade out sometime unpredictable in the late teens -- and many ghosts have the power to freeze people in their tracks, the better to scare them to death. Sure, iron and silver and salt and fire work pretty well to contain or dispel a ghost, but only finding and eliminating its source will stop a ghost permanently -- scattering ectoplasm just means the specter will be back the next night.

That's the world Lucy Carlyle lives in, as one of the three agents of Lockwood & Co., the smallest agency in London. She's somewhere in her early teens, in something like the present day, in a world where ghosts unexplainedly began to appear widely in the early 1960s. Children in her world are tougher and more self-sufficient than we're used to -- at least the ones we see -- because they are the only ones who can perform dangerous work on a nightly basis, and so society has changed to let them do that work. With all that iron and silver, and the fortunes made by adults selling them to a frightened world, Lucy's London feels Victorian, full of dark nights and ghost-fighting steel rapiers, iron chains and silver nets.

Lucy has been with Lockwood & Co. for a little over six months as The Whispering Skull begins, and things have settled to the usual work of an agency since the tumult of her first case, The Screaming Staircase. Lockwood's profile in the world has risen with that success, and agency head Anthony Lockwood -- just barely older than Lucy, though with hidden secrets and a family background that gave him a Portland Row townhouse -- is quoted in the papers semi-regularly. But their agency is still an anomaly: not just the smallest agency in London, but the only one actually run by its agents, and not by adults that used to be able to see ghosts. The Fittes agency, in the person of the odious team leader Quill Kipps, is particularly unpleasant, seeming to dog their steps wherever they go.

begins, and things have settled to the usual work of an agency since the tumult of her first case, The Screaming Staircase. Lockwood's profile in the world has risen with that success, and agency head Anthony Lockwood -- just barely older than Lucy, though with hidden secrets and a family background that gave him a Portland Row townhouse -- is quoted in the papers semi-regularly. But their agency is still an anomaly: not just the smallest agency in London, but the only one actually run by its agents, and not by adults that used to be able to see ghosts. The Fittes agency, in the person of the odious team leader Quill Kipps, is particularly unpleasant, seeming to dog their steps wherever they go.

Kipps's crew and Lockwood's find themselves in competition when a simple job of guarding an excavation at the Kensal Green Cemetery turns complicated: the grave of Edmund Bickerstaff, Victorian occultist and doctor, is an iron box containing a powerful spirit and a unique artifact. That artifact, a mirror in a frame of bones that each holds another ghost, is stolen that night -- and Inspector Barnes of DEPRAC wants it back immediately, especially after both of the thieves turn up dead within a day. Fittes and Lockwood are each independently working on the case, and the losing team will have to take out an advertisement in the local papers to proclaim the superiority of the winners.

That would be enough, but another artifact -- a skull within a jar, which the Lockwood agents keep and which may have spoken to Lucy once -- is stirring, telling her malicious secrets and asking misleading questions. Only one other agent, the legendary Marina Fittes, has ever had verified contact with a Type Three ghost, one that clearly communicates with living humans. So this skull could be a huge coup for Lockwood and Lucy...if they can get anyone else to believe them and if its whisperings don't get all of them killed first.

The dangerous magical mirror is reminiscent of some of the paraphernalia in Stroud's Bartimeus books, though the stakes in the "Lockwood & Co." books remain on a purely personal and professional level. Whispering Skull is a smart, exciting supernatural thriller for young readers (or older ones), even if it doesn't have the scope and depth of the Bartimeus trilogy. And there are hints in this book that the stakes may get larger, and possibly simultaneously more personal, as the series goes on. I look forward to seeing many more adventures of Lucy and her fellow agents.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

That's the world Lucy Carlyle lives in, as one of the three agents of Lockwood & Co., the smallest agency in London. She's somewhere in her early teens, in something like the present day, in a world where ghosts unexplainedly began to appear widely in the early 1960s. Children in her world are tougher and more self-sufficient than we're used to -- at least the ones we see -- because they are the only ones who can perform dangerous work on a nightly basis, and so society has changed to let them do that work. With all that iron and silver, and the fortunes made by adults selling them to a frightened world, Lucy's London feels Victorian, full of dark nights and ghost-fighting steel rapiers, iron chains and silver nets.

Lucy has been with Lockwood & Co. for a little over six months as The Whispering Skull

Kipps's crew and Lockwood's find themselves in competition when a simple job of guarding an excavation at the Kensal Green Cemetery turns complicated: the grave of Edmund Bickerstaff, Victorian occultist and doctor, is an iron box containing a powerful spirit and a unique artifact. That artifact, a mirror in a frame of bones that each holds another ghost, is stolen that night -- and Inspector Barnes of DEPRAC wants it back immediately, especially after both of the thieves turn up dead within a day. Fittes and Lockwood are each independently working on the case, and the losing team will have to take out an advertisement in the local papers to proclaim the superiority of the winners.

That would be enough, but another artifact -- a skull within a jar, which the Lockwood agents keep and which may have spoken to Lucy once -- is stirring, telling her malicious secrets and asking misleading questions. Only one other agent, the legendary Marina Fittes, has ever had verified contact with a Type Three ghost, one that clearly communicates with living humans. So this skull could be a huge coup for Lockwood and Lucy...if they can get anyone else to believe them and if its whisperings don't get all of them killed first.

The dangerous magical mirror is reminiscent of some of the paraphernalia in Stroud's Bartimeus books, though the stakes in the "Lockwood & Co." books remain on a purely personal and professional level. Whispering Skull is a smart, exciting supernatural thriller for young readers (or older ones), even if it doesn't have the scope and depth of the Bartimeus trilogy. And there are hints in this book that the stakes may get larger, and possibly simultaneously more personal, as the series goes on. I look forward to seeing many more adventures of Lucy and her fellow agents.

Book-A-Day 2014 Introduction and Index

Friday, December 19, 2014

Book-A-Day 2014 #353: The Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks & Caanan White

When you think "African-American military history," you automatically think "guy who writes zombie books," right? It's not just me, is it?

Max Brooks, of World War Z fame, has had a passion project for the past decade or so -- which he details in his Author's Note at the end -- and it had nothing to do with zombies. (Though you could construct a through-line involving horribly mutilated human bodies, if you wanted to.) He's been enthralled with the story of the Harlem Hellfighters -- more officially the 369th Infantry Regiment of the US Army during World War I -- since the age of eleven, and spent years working on versions of a screenplay about their exploits.

Brooks transmuted those screenplays into a graphic novel, The Harlem Hellfighters , which came out earlier this year. Art is by Caanan White, whom Brooks implies he's previously worked with, though I can't figure out on what project.

, which came out earlier this year. Art is by Caanan White, whom Brooks implies he's previously worked with, though I can't figure out on what project.

We could ask all kinds of impertinent questions about this book -- is a white guy from LA the best one to tell this story? is it really in anybody's best interest to glamorize any aspect of the most brutal and dehumanizing war in history? does the black and white presentation really work with this art entirely devoid of tones? -- but The Harlem Hellfighters accomplishes its goals well, becoming an uplifting Hollywood movie on the page and making its 21st century readers feel morally superior and firmly anti-racist. (It's in development now, so it may yet become the movie it wants to be.)