A Weblog by One Humble Bookman on Topics of Interest to Discerning Readers, Including (Though Not Limited To) Science Fiction, Books, Random Thoughts, Fanciful Family Anecdotes, Publishing, Science Fiction, The Mating Habits of Extinct Waterfowl, The Secret Arts of Marketing, Other Books, Various Attempts at Humor, The Wonders of New Jersey, the Tedious Minutiae of a Boring Life, Science Fiction, No Accounting (For Taste), And Other Weighty Matters.

Thursday, April 27, 2017

Bachelors Anonymous by P.G. Wodehouse

I find I consistently come back to Wodehouse as a palate cleaner after reading something really good. There are very few writers who can compare to Kelly Link -- whose book of short stories Get in Trouble I was reading just before Bachelors Anonymous -- but Wodehouse can stand any comparison.

Yes, his work is artificial. Yes, it's entirely constrained. Yes, it's set in a world almost entirely unlike our own in a million tiny ways. Yes a thousand yesses. But it's also magnificent in its artificiality, precise and sublime in its construction, and built with exquisite care out of words chosen to be exact and tight-fitting -- like the most brilliantly useless hypercar ever, a gleaming and glorious monument to silly excess.

And, on the other hand, I have scattered across my shelves books that are perfectly nice -- some of them may be vastly better than that, for all I know -- but were less stylistically inventive or obviously well-written than something transcendent that I read before them. When that happens, the later book feels like a trudge and a slog, and I've learned to just give up quickly at that point. So there have been a few dozen things that I read ten or fifty pages of but felt only meh. I've found, from long trial-and-error, that only one writer will consistently transcend the deadly Every-novel-is-meh Syndrome: Wodehouse. (The other path involves diving into nonfiction for a while, and is less quick. Because a book of nonfiction may also become meh.)

So Wodehouse is now my go-to after a book that would otherwise beg comparisons to anything more realistic or contemporary. Luckily, Wodehouse wrote nearly a hundred books in his life, and nearly all of them are in print in those lovely little Overlook Press hardcovers. (And I have a stuffed-full shelf of them to choose from.) This particular little morsel is from the very end of his long writing life, published in 1973, just a couple of years (literally) before Wodehouse's knighthood and subsequent death. (I am not here claiming a connection. I haven't made a serious study of the timeframe.)

As typical with Wodehouse, it's about people falling in love, or trying not to. Young men and women -- and some older ones as well -- mostly connected with the arts (a movie mogul, a playwright, a journalist, an actress...but also a lawyer or two and a nurse, eventually) who just need to find each other, struggle through the usual plot complications and settle down. This time out, though, there is an organization -- the title group, out of Hollywood -- that helps its members keep themselves unmarried rather than going around for what may be the sixth time.

Can the force of true love win out over silly misunderstandings and a pseudo-twelve-step group? Well, of course it can: this is Wodehouse.

Bachelors Anonymous is late Wodehouse, which means it's a bit short and not quite as rococo as his best, but it's sunny and amiable and funny and glorious and entirely entertaining. And, having read it, I'm ready to jump back into anything else.

Wednesday, April 26, 2017

Hot Dog Taste Test by Lisa Hanawalt

I've said before that I keep confusing the comics of Lisa Hanawalt

with those of Gemma Correll, but that's probably just me. (So many

things in this world are.) In case anyone else is laboring under this

particular handicap, the big distinction -- other than the fact that

they're entirely different people doing entirely different work, with

only slight and occasional similarities in their art -- is that Hanawalt

is American, previously in NYC and most recently (according to this

book) in LA, while Correll is British.

Hot Dog Taste Test was Hanawalt's second collection of comics, after 2013's My Dirty Dumb Eyes (which, I have to admit, I keep wanting to switch around and call "Dumb Dirty"), and collects drawings, comics, and odder elements mostly around the subject of food and eating. (Note that "what happens to food after you eat it" is something Hanawalt considers a related topic, and there are several cartoons on the other end of the alimentary canal. In particular, I like her request to rename poop "doof,"since that's food backward.)

Hanawalt has a quirky sense of humor, and is not generally trying to create conventional jokes in the works here. This is mostly observational humor from someone who probably likes more kinds of food than you do and someone who definitely thinks seriously about pooping more often than you do. I want to call her work earthy, but that may have a '60s-hippie feeling that isn't what I mean: she's earthy in a modern, totally up-to-date way, all about kale and ortolan and using time machines to see how historical people poop.

I do not think I'm doing a good job of making this book sound appealing. Maybe I should come in at this from a different direction.

Hot Dog Taste Test is funny and unique, like that one friend of yours from college who always went too far. If you could close him like a book whenever you needed to, he would be perfect, right? So here you are -- cartoons and illustrated stories and sketchbook pages and scrawled asides and doodled thoughts about poop, about stuff that goes into your mouth and comes out from lower parts. (Note: there's also some menstruation stuff: I know some of you boys freak out about that.) There's other stuff, too -- a long travel diary about her family in Argentina that doesn't have much to do with food, and another multi-page piece about swimming with otters that similarly avoids mastication, and a few pages about bird-headed people including what I think is the author self-insert character. But the through-line is food, from the pros and cons of different meals to random jokes and scribbles and paintings.

Hanawalt is funny in really specific ways, like no one else. And unique voices are to be cherished. So there you go.

Hot Dog Taste Test was Hanawalt's second collection of comics, after 2013's My Dirty Dumb Eyes (which, I have to admit, I keep wanting to switch around and call "Dumb Dirty"), and collects drawings, comics, and odder elements mostly around the subject of food and eating. (Note that "what happens to food after you eat it" is something Hanawalt considers a related topic, and there are several cartoons on the other end of the alimentary canal. In particular, I like her request to rename poop "doof,"since that's food backward.)

Hanawalt has a quirky sense of humor, and is not generally trying to create conventional jokes in the works here. This is mostly observational humor from someone who probably likes more kinds of food than you do and someone who definitely thinks seriously about pooping more often than you do. I want to call her work earthy, but that may have a '60s-hippie feeling that isn't what I mean: she's earthy in a modern, totally up-to-date way, all about kale and ortolan and using time machines to see how historical people poop.

I do not think I'm doing a good job of making this book sound appealing. Maybe I should come in at this from a different direction.

Hot Dog Taste Test is funny and unique, like that one friend of yours from college who always went too far. If you could close him like a book whenever you needed to, he would be perfect, right? So here you are -- cartoons and illustrated stories and sketchbook pages and scrawled asides and doodled thoughts about poop, about stuff that goes into your mouth and comes out from lower parts. (Note: there's also some menstruation stuff: I know some of you boys freak out about that.) There's other stuff, too -- a long travel diary about her family in Argentina that doesn't have much to do with food, and another multi-page piece about swimming with otters that similarly avoids mastication, and a few pages about bird-headed people including what I think is the author self-insert character. But the through-line is food, from the pros and cons of different meals to random jokes and scribbles and paintings.

Hanawalt is funny in really specific ways, like no one else. And unique voices are to be cherished. So there you go.

Tuesday, April 25, 2017

Bandette, Vol. 3: The House of the Green Mask by Paul Tobin and Colleen Coover

This third story of the lady thief Bandette -- after Presto! and Stealers, Keepers!

-- is just as much of a frothy, lovely souffle as the first two, and

shows that Tobin and Cooper can indeed spin this concoction out beyond

its initial lengths.

More complications and elements of this pseudo-French milieu continue to emerge in The House of the Green Mask, but all fit into the essential light-heartedness of the Bandette books: Bandette herself will always be victorious, will always be witty, will always have candy bars to celebrate a glorious theft, will always be supported by her cadre of orphans and other random denizens of this great city, and will face what seem like overwhelming odds with aplomb, style, and a smile on her face.

This is not a realistic world, and is in no danger of ever becoming one; I suppose it's an action farce, if that's a plausible term, and a farce is always highly artificial, taking place in a universe machined to minute tolerances so that the plot can race through it at high speeds and to greatest effect.

I could give more details of that plot here, but what would be the point? A souffle is in the eating. And this is a marvelous one. So go and eat it already.

More complications and elements of this pseudo-French milieu continue to emerge in The House of the Green Mask, but all fit into the essential light-heartedness of the Bandette books: Bandette herself will always be victorious, will always be witty, will always have candy bars to celebrate a glorious theft, will always be supported by her cadre of orphans and other random denizens of this great city, and will face what seem like overwhelming odds with aplomb, style, and a smile on her face.

This is not a realistic world, and is in no danger of ever becoming one; I suppose it's an action farce, if that's a plausible term, and a farce is always highly artificial, taking place in a universe machined to minute tolerances so that the plot can race through it at high speeds and to greatest effect.

I could give more details of that plot here, but what would be the point? A souffle is in the eating. And this is a marvelous one. So go and eat it already.

Monday, April 24, 2017

Well, Isn't This a Charming Disaster?

I occasionally get things other than books in my mail, and I'm supposed to be telling you people about them as well. (If this sounds entirely new to you, it's because I'm not very good at it.)

I occasionally get things other than books in my mail, and I'm supposed to be telling you people about them as well. (If this sounds entirely new to you, it's because I'm not very good at it.)But one thing -- the new record Cautionary Tales by the Brooklyn-based chamber duo Charming Disaster -- has been rolling around my head quite a lot lately, so I wanted to actually make an effort to mention it and recommend it here.

Charming Disaster is made of up of the leaders of two other bands I've never heard of -- Ellia Bisker of Sweet Soubrette and Jeff Morris of Kotorino -- plus some other musicians, I guess. (If you have heard of either of those bands -- they are likely better known than I realize, since I am out of so many loops it's a wonder I know anything -- this may intrigue you.)

And they play music that I think other SFF folks, and readers in general, will like a lot: chamber pop/cabaret influenced by folklore, mythology, pulp fiction, murder ballads, and similar odd corners of Americana, sung duet-style by two excellent singers. At the moment, I'm particularly fond of the songs "Ragnarok" (guess what it's about) and "Days Are Numbered" (two competing spies), but I've only been through the record a few times, so that may change.

Cautionary Tales was officially released April 21st (last Friday), and is available via the links above and below from Bandcamp, and from the usual corporate stores as well. It's their second full-length album -- do we still call them albums? -- after Love, Crime, & Other Trouble, which I have not heard yet.

Anyway, I think a lot of you would like this sort of thing. And, if I did it right, there will be a widget below allowing you to listen to the songs right here -- not sure if it's just snippets or the whole thing, but we'll find out together, won't we?

Reviewing the Mail: Week of 4/22

OK, so, Monday again, huh? There's always another one.

For this Monday, as with all others, I'm going to tell you about the books that came in my mail the prior week. Sometimes it's a lot (and my Sunday is full of typing, squinting at ISBNs, and trying to phrase bemused disinterest in a more positive way over and over), and sometimes it's not.

This week, it's one, which is a nice number: it gives me an excuse to make this post in the first place, lets me pretend I'm giving a spotlight to this one book on purpose, and doesn't take too much time. If the book itself looks interesting, all the better.

Wicked Wonders is that book, at least right now. It's a collection of stories by Ellen Klages, with thirteen pieces of fiction and the true-life story of "The Scary Ham." (And I am here to tell you I have already read "The Scary Ham," as I was looking at this book and make preliminary motions at my keyboard. I will tell you no more about it, but it made me want to get into Wicked Wonders more quickly than I otherwise would have.)

It's a trade paperback from Tachyon, with a classy cover that looks stealthily like whatever dull memoir of a horrible childhood all of those book-club women in your neighborhood are reading right now. Think of it as protective coloration. Read this in public, and everyone will think you've got something worthy and classy -- and they will be more right than they know.

Do I need to tell you more? I don't really know Klages -- other than running into her a couple of times, back when I was in the SF world more than I am now -- and don't know her work well, either. But I've already read one story in this book, and I want to read more. And that's the core function of a collection: to get you to read one story, and then another. So this book is successful, and you should try it yourself.

For this Monday, as with all others, I'm going to tell you about the books that came in my mail the prior week. Sometimes it's a lot (and my Sunday is full of typing, squinting at ISBNs, and trying to phrase bemused disinterest in a more positive way over and over), and sometimes it's not.

This week, it's one, which is a nice number: it gives me an excuse to make this post in the first place, lets me pretend I'm giving a spotlight to this one book on purpose, and doesn't take too much time. If the book itself looks interesting, all the better.

Wicked Wonders is that book, at least right now. It's a collection of stories by Ellen Klages, with thirteen pieces of fiction and the true-life story of "The Scary Ham." (And I am here to tell you I have already read "The Scary Ham," as I was looking at this book and make preliminary motions at my keyboard. I will tell you no more about it, but it made me want to get into Wicked Wonders more quickly than I otherwise would have.)

It's a trade paperback from Tachyon, with a classy cover that looks stealthily like whatever dull memoir of a horrible childhood all of those book-club women in your neighborhood are reading right now. Think of it as protective coloration. Read this in public, and everyone will think you've got something worthy and classy -- and they will be more right than they know.

Do I need to tell you more? I don't really know Klages -- other than running into her a couple of times, back when I was in the SF world more than I am now -- and don't know her work well, either. But I've already read one story in this book, and I want to read more. And that's the core function of a collection: to get you to read one story, and then another. So this book is successful, and you should try it yourself.

Wednesday, April 19, 2017

Get in Trouble by Kelly Link

There's a cliche that you should read short-story collections slowly -- picking it up, reading one story, and putting it back down until it's time for the next one, so each story has an individual impact. You see it a lot in laudatory introductions and reviews, when writers are digging deep in their sack of tricks to pull out the biggest compliment they can think of for their mentors or best friends or idols. And maybe some people really do read like that on purpose: I don't know how everyone reads, but I know enough to know that there's a lot of people who do things in ways I find really weird.

So when I say that I read Kelly Link's third major short-story collection Get in Trouble one story a time, one or occasionally two a day and missing a lot of days, over what turned out to be three weeks, please understand that I'm not saying that standard compliment I just described. I'm perfectly capable of reading one short story and then picking up another one right away -- at least most of the time, when there's enough time to get through the next one.

And I have to admit that part of my slowness is just the way my life is now: I read mostly during my commute, and sometimes that's too hectic to get a book out (or even get a seat). And a book of longer stories, like this one, means that one leg of a commute is probably only one story long anyway.

But, still. After each of the first few stories in this book -- three? four? I can't remember exactly, now -- I had to stop, put the book down for at least a moment, and take it all in. It had been a while since I last read Link: I knew, intellectually, how good she was, but I didn't feel it, viscerally, until those stories started hitting me. She's a writer whose stories end precisely: on exactly the right few words, at exactly the right moment. And they pack a wallop.

A writer like that doesn't get a lot of work out, of course. Get in Trouble is only the third Link collection, after Stranger Things Happen and Magic for Beginners. It collects roughly a decade's worth of work -- nine stories from 2006 through 2014, including one new one for this volume. It would be nice to have more Kelly Link stories, definitely. But only if they could be as good as these, and that's a very high bar. Maybe the next decade will be more productive for her, maybe not. In life, you get what you get.

So here are nine great stories, some of which you may have read before if you're really plugged in. (I hadn't; this last decade has seen me getting very un-plugged.) They're mostly fantasy, in that they have strange and mysterious elements in them that don't fit what we think of as normal reality. At least one is also science fiction. They mostly are about women, which still is not as common in SFF as it should be, and worth celebrating. They're also largely about young people -- maybe because we think stories happen to young people.

I can't tell you more than that about them. You have to read them. You should read them. Even if you don't read much short fiction, or fantasy, or fiction at all. I think Kelly Link will be read a hundred years from now, and taught. I think there will be long dissertations on her stories. And, more importantly, I think those students in 2117 "forced" to read the Penguin Classics edition of Link's stories will realize that they're still wonderful, because they will be.

So when I say that I read Kelly Link's third major short-story collection Get in Trouble one story a time, one or occasionally two a day and missing a lot of days, over what turned out to be three weeks, please understand that I'm not saying that standard compliment I just described. I'm perfectly capable of reading one short story and then picking up another one right away -- at least most of the time, when there's enough time to get through the next one.

And I have to admit that part of my slowness is just the way my life is now: I read mostly during my commute, and sometimes that's too hectic to get a book out (or even get a seat). And a book of longer stories, like this one, means that one leg of a commute is probably only one story long anyway.

But, still. After each of the first few stories in this book -- three? four? I can't remember exactly, now -- I had to stop, put the book down for at least a moment, and take it all in. It had been a while since I last read Link: I knew, intellectually, how good she was, but I didn't feel it, viscerally, until those stories started hitting me. She's a writer whose stories end precisely: on exactly the right few words, at exactly the right moment. And they pack a wallop.

A writer like that doesn't get a lot of work out, of course. Get in Trouble is only the third Link collection, after Stranger Things Happen and Magic for Beginners. It collects roughly a decade's worth of work -- nine stories from 2006 through 2014, including one new one for this volume. It would be nice to have more Kelly Link stories, definitely. But only if they could be as good as these, and that's a very high bar. Maybe the next decade will be more productive for her, maybe not. In life, you get what you get.

So here are nine great stories, some of which you may have read before if you're really plugged in. (I hadn't; this last decade has seen me getting very un-plugged.) They're mostly fantasy, in that they have strange and mysterious elements in them that don't fit what we think of as normal reality. At least one is also science fiction. They mostly are about women, which still is not as common in SFF as it should be, and worth celebrating. They're also largely about young people -- maybe because we think stories happen to young people.

I can't tell you more than that about them. You have to read them. You should read them. Even if you don't read much short fiction, or fantasy, or fiction at all. I think Kelly Link will be read a hundred years from now, and taught. I think there will be long dissertations on her stories. And, more importantly, I think those students in 2117 "forced" to read the Penguin Classics edition of Link's stories will realize that they're still wonderful, because they will be.

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

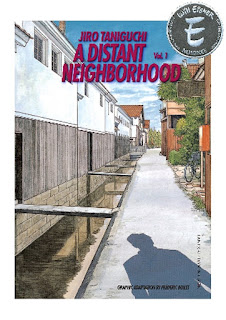

A Distant Neighborhood, Vol. 1 by Jiro Taniguchi

Usually, I would try to hold a two-book series to review together. But I got A Distant Neighborhood, Vol. 1 from the library, and there's no telling when that library will disgorge Vol. 2, so I might as well type now while the book is in front of me and my memories are as clear as they'll ever be.

A great transition here would be to say that this book -- a manga originally written and drawn in 1998 by Jiro Taniguchi -- is all about memory, but that's really not true. It's a time-slip book, so it's about the realness of the past rather than the way we remember and remake the past in the present. Distant Neighborhood is a fantasy, because its central events are the impossible ones millions of us have thought about and wished for and mulled over.

We can't actually go back to being fourteen again, back in our old (young) body, living with our still-young parents, going to school. Can't slough off the life of a middle-aged businessman to start over as a kid. But that's just what happens to Hiroshi Nakahara in this book: he accidentally takes the wrong train back from a business trip, ending up in his home town for the first time in many years. He goes to his mother's grave, to pray or meditate or just have a quiet moment, and when he gets back up it's more than thirty years earlier. The father who ran off is still there, the mother who later died is young and vibrant, and the eighth grade is just about to start.

Hiroshi at first wants to go back to his old life -- he worries about his wife and two daughters, even though he neglects them most of the time -- but then sinks back into the life of a junior high schooler. It's easy for him, the second time around: the gym classes he hated originally now showcase how young and fit he is; the academics are both easier than his future job and entirely about concepts he already learned once. He does have some trouble keeping his secret, since he's used to being a responsible adult, not a child in regimented early-60s Japan, but he mostly manages to act like a plausible young teen, if a more poised and mature one than he was the first time around.

This is only the first half of the story, of course. Hiroshi wants to stop his father from walking out on the family, which he's going to do, in a few months. That doesn't happen in this volume, either way. But Hiroshi does connect with his father and grandmother on an adult level in a way he didn't when he was actually fourteen years old. And that leads to his learning how his parents actually met -- a sadder story than he expected, at the end of World War II.

Someday soon, I will know how this story ends. Maybe Hiroshi will pop back into his middle-aged life after doing something specific as a teen -- some moment that he had to live over to learn a lesson or set something right. Maybe he'll just keep moving forward in time, like everyone else, given a second chance. Maybe something completely unexpected. Whatever happens, I'm confident Taniguchi will tell that story cleanly, precisely, and deeply, just like the first half.

I'd heard Taniguchi's name for a while, but I'm sorry to say it took his recent death to get me to read his books. He's a smart, adult story-teller here, focused on character and nuance in dialogue and narration and art, acutely attuned to small moments and shifts of emotion. He's one of the great ones, I think -- and I'm sorry it took the end of his career to get me to experience his work.

A great transition here would be to say that this book -- a manga originally written and drawn in 1998 by Jiro Taniguchi -- is all about memory, but that's really not true. It's a time-slip book, so it's about the realness of the past rather than the way we remember and remake the past in the present. Distant Neighborhood is a fantasy, because its central events are the impossible ones millions of us have thought about and wished for and mulled over.

We can't actually go back to being fourteen again, back in our old (young) body, living with our still-young parents, going to school. Can't slough off the life of a middle-aged businessman to start over as a kid. But that's just what happens to Hiroshi Nakahara in this book: he accidentally takes the wrong train back from a business trip, ending up in his home town for the first time in many years. He goes to his mother's grave, to pray or meditate or just have a quiet moment, and when he gets back up it's more than thirty years earlier. The father who ran off is still there, the mother who later died is young and vibrant, and the eighth grade is just about to start.

Hiroshi at first wants to go back to his old life -- he worries about his wife and two daughters, even though he neglects them most of the time -- but then sinks back into the life of a junior high schooler. It's easy for him, the second time around: the gym classes he hated originally now showcase how young and fit he is; the academics are both easier than his future job and entirely about concepts he already learned once. He does have some trouble keeping his secret, since he's used to being a responsible adult, not a child in regimented early-60s Japan, but he mostly manages to act like a plausible young teen, if a more poised and mature one than he was the first time around.

This is only the first half of the story, of course. Hiroshi wants to stop his father from walking out on the family, which he's going to do, in a few months. That doesn't happen in this volume, either way. But Hiroshi does connect with his father and grandmother on an adult level in a way he didn't when he was actually fourteen years old. And that leads to his learning how his parents actually met -- a sadder story than he expected, at the end of World War II.

Someday soon, I will know how this story ends. Maybe Hiroshi will pop back into his middle-aged life after doing something specific as a teen -- some moment that he had to live over to learn a lesson or set something right. Maybe he'll just keep moving forward in time, like everyone else, given a second chance. Maybe something completely unexpected. Whatever happens, I'm confident Taniguchi will tell that story cleanly, precisely, and deeply, just like the first half.

I'd heard Taniguchi's name for a while, but I'm sorry to say it took his recent death to get me to read his books. He's a smart, adult story-teller here, focused on character and nuance in dialogue and narration and art, acutely attuned to small moments and shifts of emotion. He's one of the great ones, I think -- and I'm sorry it took the end of his career to get me to experience his work.

Monday, April 17, 2017

Reviewing the Mail: Week of 4/15

Every week, I list whatever books came in my mail here, because I feel like I should do something to publicize them, and I'm certainly not reading them quickly enough.

Publicity, though, increasingly has shifted to electronic copies -- which are both cheaper and vastly easier to control -- and even print copies tend to go out to outlets that have made some kind of commitment to cover them. (And I tend not to make commitments that I know I won't live up to.)

So this is another week with no books. I actually kinda like those weeks, since it makes the "job" of typing this post much quicker and easier. At some point, if there's a long enough string of no-book weeks, I may stop doing this post entirely. That will be sad, since I'm not one to give up on any habit, no matter how pointless.

Anyway, I've got four books I read last week that I want to write about, and it's Easter morning (meaning family frivolity and eating will take up much of the day), so let me try to get to that.

Publicity, though, increasingly has shifted to electronic copies -- which are both cheaper and vastly easier to control -- and even print copies tend to go out to outlets that have made some kind of commitment to cover them. (And I tend not to make commitments that I know I won't live up to.)

So this is another week with no books. I actually kinda like those weeks, since it makes the "job" of typing this post much quicker and easier. At some point, if there's a long enough string of no-book weeks, I may stop doing this post entirely. That will be sad, since I'm not one to give up on any habit, no matter how pointless.

Anyway, I've got four books I read last week that I want to write about, and it's Easter morning (meaning family frivolity and eating will take up much of the day), so let me try to get to that.

Wednesday, April 12, 2017

Mooncop by Tom Gauld

If Jim Ballard had mellowed into a gentle wryness in his extreme old age, he might have provided a script for a book like Mooncop, the story of a man left behind by a now-fading space age, one guy left to do a pointless job in a place beautiful and hard and cold and alien.

But Ballard is dead, and he never mellowed -- that was the beauty of Ballard, actually. He just got more concentrated, like a good wine aging into brandy. So we needed Tom Gauld to tell this story, in words and pictures, and I have no idea if Ballard ever came into Gauld's mind while he was writing or drawing Mooncop. (I'd like to think he did, at least for a moment.)

There is one cop on the moon. We don't know his name; everyone just calls him "Officer." Not that there's a lot of everyone -- the moon is emptying out, for whatever reason, with employees being transferred back down to earth and pensioners moving to be with their children and space museums moving to places where they'll get tourists. There are few people on the moon when Mooncop opens, and even fewer when it ends.

Robots replace some of the people -- not always with good reason, not always all that well, but that's life. Everybody has plans and budgets and expectations, and when the man running a shop on the moon moves to Holland, you send up a replacement. Maybe that replacement is a robot, and maybe the company hasn't really thought through the demand for that shop among a shrinking lunar population. But life goes on, and there's a cop to keep things running smoothly, if anything unsmooth ever happens.

It doesn't. It hasn't for a long time, if ever, and our Officer is a little sad, a little bored, a little fed-up, and more than a little ready to go somewhere else. Somewhere that isn't emptying out.

He doesn't quite get what he wants -- who does? -- but he gets something, in the end. As with all of Tom Gauld's work -- the short comics in You're All Just Jealous of My Jetpack, the previous graphic novel Goliath -- Gauld is understated and quiet and observational rather than obvious and pointed. Gauld's characters are all Everymen and -women, rubbery arms and nearly-blank faces leaving them just individual enough to talk to each other.

We are all Mooncop. That's all I'm saying. This is my story as much as anyone else's. It's probably yours as well, if you're old enough. Gauld is good at that -- at making a particular thing that is more than just its particulars.

Mooncop isn't the book most people would think of when they think of a title like Mooncop. But if you like the moon, or cops, or quiet stories, or the futures that didn't happen -- or if you've just been knocked around a bit by life, I think you'll enjoy it.

But Ballard is dead, and he never mellowed -- that was the beauty of Ballard, actually. He just got more concentrated, like a good wine aging into brandy. So we needed Tom Gauld to tell this story, in words and pictures, and I have no idea if Ballard ever came into Gauld's mind while he was writing or drawing Mooncop. (I'd like to think he did, at least for a moment.)

There is one cop on the moon. We don't know his name; everyone just calls him "Officer." Not that there's a lot of everyone -- the moon is emptying out, for whatever reason, with employees being transferred back down to earth and pensioners moving to be with their children and space museums moving to places where they'll get tourists. There are few people on the moon when Mooncop opens, and even fewer when it ends.

Robots replace some of the people -- not always with good reason, not always all that well, but that's life. Everybody has plans and budgets and expectations, and when the man running a shop on the moon moves to Holland, you send up a replacement. Maybe that replacement is a robot, and maybe the company hasn't really thought through the demand for that shop among a shrinking lunar population. But life goes on, and there's a cop to keep things running smoothly, if anything unsmooth ever happens.

It doesn't. It hasn't for a long time, if ever, and our Officer is a little sad, a little bored, a little fed-up, and more than a little ready to go somewhere else. Somewhere that isn't emptying out.

He doesn't quite get what he wants -- who does? -- but he gets something, in the end. As with all of Tom Gauld's work -- the short comics in You're All Just Jealous of My Jetpack, the previous graphic novel Goliath -- Gauld is understated and quiet and observational rather than obvious and pointed. Gauld's characters are all Everymen and -women, rubbery arms and nearly-blank faces leaving them just individual enough to talk to each other.

We are all Mooncop. That's all I'm saying. This is my story as much as anyone else's. It's probably yours as well, if you're old enough. Gauld is good at that -- at making a particular thing that is more than just its particulars.

Mooncop isn't the book most people would think of when they think of a title like Mooncop. But if you like the moon, or cops, or quiet stories, or the futures that didn't happen -- or if you've just been knocked around a bit by life, I think you'll enjoy it.

Tuesday, April 11, 2017

Giant Days, Vol. 4 by Allison and Sarin

I go back and forth about putting full author names in the titles of my posts, especially with comics. Is that title too long? Is this one too terse and uninformative? Today's book has a short title to begin with, and only two major contributors (well, unless you count cover artist Lissa Treiman, inker Liz Fleming, colorist Whitney Cogar, and letterer Jim Campbell, which I guess I am, now), so throwing a "John" and a "Max" into that title would have been just fine.

But I just typed a damn paragraph about how I didn't include those in the title, so I'll be damned if I go back on it now.

Anyway: Giant Days, Vol. 4. The latest collection of the comics series written by John Allison, penciled by Max Sarin and everything-elsed by the people I mentioned above. (See my reviews of volumes one, two, and three.) It's loosely related to Allison's webcomics Scarygoround and Bad Machinery -- the former slightly, the latter not really at all other than sharing a world. But you don't really need to have read any of that.

Esther, Susan, and Daisy are students in their first year at a minor British university, sometime in the spring semester as winter is losing hold. They're looking at housing for the next year, since they don't want to be stuck in the dorms with girls like they were six months ago. They're variously getting over failed love affairs, looking for jobs, and trying to pass their classes. They're normal people, the kind that are still rare in comics.

They're also very funny and real and interesting -- and so are their friends and the various background people they run into. Allison writes zingy dialogue like no one else, and the art has a slightly animation-derived energy and verve.

Look, if you ever were a college student, you'll find a lot to love. If you are one now, even more so. If you're female, I expect you'll identify with at least one of the core trio. And if you're male, you still might. (I myself am totally a Susan and am not ashamed to admit it.)

These books come out quickly, since each one only collects four issues. I'm going to keep reading them and telling you how great they are. You might as well catch up now, while it's easy.

But I just typed a damn paragraph about how I didn't include those in the title, so I'll be damned if I go back on it now.

Anyway: Giant Days, Vol. 4. The latest collection of the comics series written by John Allison, penciled by Max Sarin and everything-elsed by the people I mentioned above. (See my reviews of volumes one, two, and three.) It's loosely related to Allison's webcomics Scarygoround and Bad Machinery -- the former slightly, the latter not really at all other than sharing a world. But you don't really need to have read any of that.

Esther, Susan, and Daisy are students in their first year at a minor British university, sometime in the spring semester as winter is losing hold. They're looking at housing for the next year, since they don't want to be stuck in the dorms with girls like they were six months ago. They're variously getting over failed love affairs, looking for jobs, and trying to pass their classes. They're normal people, the kind that are still rare in comics.

They're also very funny and real and interesting -- and so are their friends and the various background people they run into. Allison writes zingy dialogue like no one else, and the art has a slightly animation-derived energy and verve.

Look, if you ever were a college student, you'll find a lot to love. If you are one now, even more so. If you're female, I expect you'll identify with at least one of the core trio. And if you're male, you still might. (I myself am totally a Susan and am not ashamed to admit it.)

These books come out quickly, since each one only collects four issues. I'm going to keep reading them and telling you how great they are. You might as well catch up now, while it's easy.

Monday, April 10, 2017

Reviewing the Mail: Week of 4/8

Every Monday I post here about the books that came in the mail the previous week. This time out, I have one book from Tor, related to a TV show some of you may love. (I haven't seen it, but I watch so little TV that saying that is meaningless: I don't watch anything.)

The book is The Librarians and the Mother Goose Chase, and no points for guessing what the TV show is. (Well, if you've never heard of it, I guess I can tell you it's called The Librarians, and it's about librarians. The fictional kind that save the world from supernatural stuff, not the real kind that shelve books and fill out paperwork and spend a lot of time talking to the people who hang out in libraries during the day.) This book, by Greg Cox, is about a secret book of spells -- by a woman named Goose, who I'm sorry to say was a mother -- from the 18th century that has reappeared, wreaking havoc and all of the usual jazz. So the librarians need to find and stop it -- wrap it in that tough clear plastic, put a little pocket in the back and a sticker on the spine with the LOC number, and place it carefully in the Rare Books Room where it can only be read with little white gloves. (I may be misunderstanding the exact control mechanisms, here.)

Mother Goose Chase is a trade paperback, and it hits stores on April 25th. If you like both books and TV, this is a book about people on TV that care about books, so I don't see how you can go wrong.

The book is The Librarians and the Mother Goose Chase, and no points for guessing what the TV show is. (Well, if you've never heard of it, I guess I can tell you it's called The Librarians, and it's about librarians. The fictional kind that save the world from supernatural stuff, not the real kind that shelve books and fill out paperwork and spend a lot of time talking to the people who hang out in libraries during the day.) This book, by Greg Cox, is about a secret book of spells -- by a woman named Goose, who I'm sorry to say was a mother -- from the 18th century that has reappeared, wreaking havoc and all of the usual jazz. So the librarians need to find and stop it -- wrap it in that tough clear plastic, put a little pocket in the back and a sticker on the spine with the LOC number, and place it carefully in the Rare Books Room where it can only be read with little white gloves. (I may be misunderstanding the exact control mechanisms, here.)

Mother Goose Chase is a trade paperback, and it hits stores on April 25th. If you like both books and TV, this is a book about people on TV that care about books, so I don't see how you can go wrong.

Tuesday, April 04, 2017

The Back Three-Quarters of iZombie by Chris Roberson and the Allreds

I normally credit comics to the writer and the artist, but colorists are really important, too, and Laura Allred's color work is so much part of what we think of as "Michael Allred art" that not mentioning her is a big oversight. Hence, the title of this post.

Some time back, I read the first volume of iZombie, written by novelist/publishing entrepreneur/great guy Chris Roberson, drawn by Michael Allred, and colored by Laura Allred (who I didn't credit as strongly at the time). By that point the series was already done and collected, but I can be slow to catch up with things....so, three years later, here I am with the rest of it.

(In between, the general idea has become a TV show I've never seen. I hear it's very different but not bad, and I hope it's generating big checks for Roberson and the Allreds.)

My vague memory is that iZombie was originally planned to be an ongoing series, and it got a cancellation order somewhere in the middle, with enough lead-time to get to a satisfying ending. Which may be true, or maybe my memory is wrong, because this story feels organic and complete -- the four volumes of iZombie tell one story and firmly shut the door on that story, in a way very unusual for Big Two comics. (Of course, iZombie was from Vertigo, and the credits indicate that the creators actually own the copyright, which makes a huge difference.)

Gwen Dylan is a zombie -- dead but still walking around, and in possession of most of her memories and thoughts as long as she gets a regular diet of fresh brains -- in the lovely town of Eugene, Oregon, where she lives in a crypt convenient for her gravedigging job. (Done by hand with shovels here, which I understand is at the very least very, very retro.) Her two new post-death friends are the '60s ghost Ellie and were-terrier (like a werewolf, but cuter and more civilized) Scott.

If this were a long-running serialized comic, it would be about that trio -- solving crimes, foiling plots, helping people, hanging out, and getting on with their lives. Some of that does happen here, but iZombie turned out to be a very plotty book, so they have to compete for page time with the ancient Egyptian mummy Amon, the various monster-killing agents of the Fossor Corporation (including a cute guy Gwen dates), the Dead Presidents (the requisite super-secret government agency that uses monsters as agents), Amon's ex-girlfriend (a Elsa Lancaster-haired revived-corpse-turned-mad-scientist) and her new vampire henchwoman, both Gwen's old best friend and her forgotten-since-death kid brother, Scott's dead grandfather (now in a chimp body), a supernatural Shadowesque crime fighter who gets mostly crowded out by other things, a Russian brain-in-a-Mr-Coffee and his hulking henchman, the local band of vampires, and Scott's co-workers/D&D group.

There's a mildly apocalyptic zombie invasion -- from the secret tunnels under Eugene -- that pops up in the third volume, leading the usually-enemies Fossors and Dead Presidents to stand back-to-back killing monsters in cool fashion, which we all expected would happen.

But that's just a warm-up for the real apocalypse: the Lovecraftian entity Xitalu is about to squeeze into our reality from the spaces between and eat our world, if not stopped through mass sacrifice. And several of the people mentioned about want to try to control Xitalu, which may be possible (or maybe not) but is definitely crazy and suicidal. Amon's plan to drive off Xitalu is not much better, though.

And then it all ends. Really. This is a major comics series with a realio trulio ending that's not just a springboard for more stories. (Well, it's not impossible to tell more stories about Gwen, but they would be radically different from this and involve none of the rest of the cast.)

It's all bit overstuffed, particularly towards the end. I don't know how much warning the creators had about the impending end, but it feels like some events might have happened differently, and some elements might have been spaced out more, if iZombie was likely to keep running another year or two. Now, both urban fantasy and superhero comics -- two of iZombie's most obvious parents -- tend to be overstuffed with characters and concepts and plots anyway, so this is not unexpected. And it does all come together in the end, even if we wonder about a few of the loose ends. (What was the deal with the Phantasm, anyway?)

In the end, iZombie is Big Concept urban fantasy in comics form, as much about a girl thrust into a supernatural world (with some supernatural hunky guys, natch) as anything else. And her choices, as usual for the genre, drive the story. Comics don't focus on women and their choices all that much, so this is entirely a good thing -- even aside from Gwen, a lot of the driving forces of iZombie are women, from that vampire "sorority" to Ellie to Galatea (the villain, more or less). It might be slightly rushed and slightly too full, but Gwen is a compelling central character who interacts with an amusingly odd collection of folks and manages to save the world in the end. And that's entirely a good thing.

These three books are titled uVampire, Six Feet Under and Rising, and Repossession. They're still available, and (along with the first book, linked way above) tell one complete story. More comics should do that.

Some time back, I read the first volume of iZombie, written by novelist/publishing entrepreneur/great guy Chris Roberson, drawn by Michael Allred, and colored by Laura Allred (who I didn't credit as strongly at the time). By that point the series was already done and collected, but I can be slow to catch up with things....so, three years later, here I am with the rest of it.

(In between, the general idea has become a TV show I've never seen. I hear it's very different but not bad, and I hope it's generating big checks for Roberson and the Allreds.)

My vague memory is that iZombie was originally planned to be an ongoing series, and it got a cancellation order somewhere in the middle, with enough lead-time to get to a satisfying ending. Which may be true, or maybe my memory is wrong, because this story feels organic and complete -- the four volumes of iZombie tell one story and firmly shut the door on that story, in a way very unusual for Big Two comics. (Of course, iZombie was from Vertigo, and the credits indicate that the creators actually own the copyright, which makes a huge difference.)

Gwen Dylan is a zombie -- dead but still walking around, and in possession of most of her memories and thoughts as long as she gets a regular diet of fresh brains -- in the lovely town of Eugene, Oregon, where she lives in a crypt convenient for her gravedigging job. (Done by hand with shovels here, which I understand is at the very least very, very retro.) Her two new post-death friends are the '60s ghost Ellie and were-terrier (like a werewolf, but cuter and more civilized) Scott.

If this were a long-running serialized comic, it would be about that trio -- solving crimes, foiling plots, helping people, hanging out, and getting on with their lives. Some of that does happen here, but iZombie turned out to be a very plotty book, so they have to compete for page time with the ancient Egyptian mummy Amon, the various monster-killing agents of the Fossor Corporation (including a cute guy Gwen dates), the Dead Presidents (the requisite super-secret government agency that uses monsters as agents), Amon's ex-girlfriend (a Elsa Lancaster-haired revived-corpse-turned-mad-scientist) and her new vampire henchwoman, both Gwen's old best friend and her forgotten-since-death kid brother, Scott's dead grandfather (now in a chimp body), a supernatural Shadowesque crime fighter who gets mostly crowded out by other things, a Russian brain-in-a-Mr-Coffee and his hulking henchman, the local band of vampires, and Scott's co-workers/D&D group.

There's a mildly apocalyptic zombie invasion -- from the secret tunnels under Eugene -- that pops up in the third volume, leading the usually-enemies Fossors and Dead Presidents to stand back-to-back killing monsters in cool fashion, which we all expected would happen.

But that's just a warm-up for the real apocalypse: the Lovecraftian entity Xitalu is about to squeeze into our reality from the spaces between and eat our world, if not stopped through mass sacrifice. And several of the people mentioned about want to try to control Xitalu, which may be possible (or maybe not) but is definitely crazy and suicidal. Amon's plan to drive off Xitalu is not much better, though.

And then it all ends. Really. This is a major comics series with a realio trulio ending that's not just a springboard for more stories. (Well, it's not impossible to tell more stories about Gwen, but they would be radically different from this and involve none of the rest of the cast.)

It's all bit overstuffed, particularly towards the end. I don't know how much warning the creators had about the impending end, but it feels like some events might have happened differently, and some elements might have been spaced out more, if iZombie was likely to keep running another year or two. Now, both urban fantasy and superhero comics -- two of iZombie's most obvious parents -- tend to be overstuffed with characters and concepts and plots anyway, so this is not unexpected. And it does all come together in the end, even if we wonder about a few of the loose ends. (What was the deal with the Phantasm, anyway?)

In the end, iZombie is Big Concept urban fantasy in comics form, as much about a girl thrust into a supernatural world (with some supernatural hunky guys, natch) as anything else. And her choices, as usual for the genre, drive the story. Comics don't focus on women and their choices all that much, so this is entirely a good thing -- even aside from Gwen, a lot of the driving forces of iZombie are women, from that vampire "sorority" to Ellie to Galatea (the villain, more or less). It might be slightly rushed and slightly too full, but Gwen is a compelling central character who interacts with an amusingly odd collection of folks and manages to save the world in the end. And that's entirely a good thing.

These three books are titled uVampire, Six Feet Under and Rising, and Repossession. They're still available, and (along with the first book, linked way above) tell one complete story. More comics should do that.

Monday, April 03, 2017

Reviewing the Mail: Week of 4/1

This week, I have lots and lots of books that you in particular will absolutely love -- better books than you thought could possibly exist, including several long-lost masterpieces from your favorite dead authors and new phenoms that you've managed not to hear about even though they have a dozen great books out each!

No, sorry, that's an April Fool's. No such thing.

Actually, this is one of those weeks when no books arrived, so instead I get to type pointlessly here for a short while, and then schedule it to post, proving that I still exist but not doing much else constructive.

See you next week....

No, sorry, that's an April Fool's. No such thing.

Actually, this is one of those weeks when no books arrived, so instead I get to type pointlessly here for a short while, and then schedule it to post, proving that I still exist but not doing much else constructive.

See you next week....

Saturday, April 01, 2017

Read in March

And here's the list of books that passed under my eyeballs for yet another month, for those of you nosy enough to care about what another person is reading. (And who hasn't tried to figure out what the person next to you on the train/bus/subway was reading?) Here: I'll make it easy for you.

Grant Morrison, Chas Truog, and Doug Hazlewood, Animal Man, Vol. 3: Deux Ex Machina (3/1)

Paul Collins, Duel With the Devil (3/1)

Neil Gaiman, Trigger Warning (3/8)

Moebius, The World of Edena (3/13)

Grant Morrison and Dave McKean, Batman: Arkham Asylum (3/15)

Paul Pope, 100% (3/16)

Brian K. Vaughan and Cliff Chiang, Paper Girls, Vol. 2 (3/20)

Jeff Lemire and Dustin Nguyen, Descender, Vol. 2 (3/22)

Chris Roberson and Mike Allred, iZombie, Vol. 2: uVampire (3/27)

Chris Roberson and Mike Allred, iZombie, Vol. 3: Six Feet Under and Rising (3/28)

Chris Roberson and Mike Allred, iZombie, Vol. 4: Repossession (3/29)

Yup, that's less than usual. I'm now working from home more than I used to -- two-hour commutes will drive you to that -- which means less train-time, which means less reading. (And super-crowded trains when I am commuting are doing their part as well; it's hard to read a book when you're crammed into a vestibule standing up.) I keep thinking I'll carve out more time to read at home, and maybe I will...next month.

Grant Morrison, Chas Truog, and Doug Hazlewood, Animal Man, Vol. 3: Deux Ex Machina (3/1)

Paul Collins, Duel With the Devil (3/1)

Neil Gaiman, Trigger Warning (3/8)

Moebius, The World of Edena (3/13)

Grant Morrison and Dave McKean, Batman: Arkham Asylum (3/15)

Paul Pope, 100% (3/16)

Brian K. Vaughan and Cliff Chiang, Paper Girls, Vol. 2 (3/20)

Jeff Lemire and Dustin Nguyen, Descender, Vol. 2 (3/22)

Chris Roberson and Mike Allred, iZombie, Vol. 2: uVampire (3/27)

Chris Roberson and Mike Allred, iZombie, Vol. 3: Six Feet Under and Rising (3/28)

Chris Roberson and Mike Allred, iZombie, Vol. 4: Repossession (3/29)

Yup, that's less than usual. I'm now working from home more than I used to -- two-hour commutes will drive you to that -- which means less train-time, which means less reading. (And super-crowded trains when I am commuting are doing their part as well; it's hard to read a book when you're crammed into a vestibule standing up.) I keep thinking I'll carve out more time to read at home, and maybe I will...next month.