Every week, your host -- the laziest of all book-bloggers -- posts on Monday morning a lightly annotated list of the books that arrived in his mail the week before, in a transparent attempt to dodge the fact that he fails to review most of the books that he does receive.

That time has come around once again.

I have two books this week, neither of which I've read yet and neither of which I can promise I will read any time soon. Maybe I will, though! Hope is free and never-ending.

Those two books are....

Go Forth and Multiply, a new reprint anthology -- those words in that order mean "a bunch of great stories that originally appeared other places, gathered together by an expert for your reading pleasure" -- edited by the estimable Gordon Van Gelder and published by the previously-unknown-to-me Surinam Turtle Press. It collects a dozen stories, from 1949 through 1974, on the subject of repopulating the world (or a world) with humanity -- a topic I don't think has been the subject of any anthology before. It's got stories by well-known names like Poul Anderson, Damon Knight, Randall Garrett, Kate Wilhelm, and Robert Sheckley, but also from people I don't know like Sherwood Springer, Alice Eleanor Jones, and Rex Jatke. It's an anthology with a new idea, assembled by an expert, with a quirky list of stories -- what's not to love?

And then I have the new book in the Imager Portfolio series by L.E. Modesitt, Jr., Assassin's Price. (I find assassins are sometimes very expensive, but if you wait for sales and use coupons, you can obtain their services for a quite reasonable rate.) This is the eleventh book in a series I've never read, so what I can tell you about it is that it features a guy named Charyn and that it follows the books Madness in Solidar and Treachery's Tools (which I suggest you read first). This is a Tor hardcover the hit stores last week.

A Weblog by One Humble Bookman on Topics of Interest to Discerning Readers, Including (Though Not Limited To) Science Fiction, Books, Random Thoughts, Fanciful Family Anecdotes, Publishing, Science Fiction, The Mating Habits of Extinct Waterfowl, The Secret Arts of Marketing, Other Books, Various Attempts at Humor, The Wonders of New Jersey, the Tedious Minutiae of a Boring Life, Science Fiction, No Accounting (For Taste), And Other Weighty Matters.

Monday, July 31, 2017

Saturday, July 29, 2017

Incoming Books: July 26

Explaining the details is tedious and you certainly don't care -- so let's just say that I had a gift card I wanted to make sure I used up, since I'd already had it a long time. So I bought a bunch of stuff for myself online.

And, when I buy "stuff," nearly all of it will be books. (I also got Beth Orton's newish record Kidsticks, which I haven't yet pulled out of the plastic and ripped to this computer. But I hear this one is more electronic, which should be fun.)

One of those books will take some time to get here. But the rest are here, and they are:

Giant Days: Not on the Test Edition, Vol. 1 by John Allison, Lissa Treiman and Max Sarin -- How can you know if a comics series will be popular enough to spawn a hardcover reprint series? It's maddening. In some cases (like Hellboy) the hardcovers start up twenty years after the paperbacks, so at least it doesn't feel like buying the same thing immediately afterward. Look, I'm happy to have these stories in a nicer hardcover, and more happy to have the first of Allison's three self-published stories included here. But I'd rather have bought this instead of the two paperbacks, not afterward. And comics' backwards publishing schedule makes that difficult.

Dragons: The Modern Infestation by Pamela Wharton Blanpied -- I read and bought this for the SFBC back in the day (I think I bought it), but I lost my copy in the flood. I want to read it again to see if it's still as weird and sly as I remember.

Dragons: The Modern Infestation by Pamela Wharton Blanpied -- I read and bought this for the SFBC back in the day (I think I bought it), but I lost my copy in the flood. I want to read it again to see if it's still as weird and sly as I remember.

White Noise by Don DeLillo -- We all seem to be living in the free-floating anxiety of a DeLillo novel these days, so I've been thinking about this book a lot. I haven't read it since my big run through DeLillo in the late '90s, and, as you know Bob, that was a long time ago.

White Noise by Don DeLillo -- We all seem to be living in the free-floating anxiety of a DeLillo novel these days, so I've been thinking about this book a lot. I haven't read it since my big run through DeLillo in the late '90s, and, as you know Bob, that was a long time ago.

Paul Up North by Michel Rabagliati -- The latest in the loose (and loosely autobiographical) series by a great Francophone Canadian cartoonist, translated by Helge Dascher (without whom, I'm coming to think, a good half of the comics I like would never make it to America). I looked for this in a store several times, but eventually the hegemonic online retailer got my money. You snooze, you lose, small retailers.

Paul Up North by Michel Rabagliati -- The latest in the loose (and loosely autobiographical) series by a great Francophone Canadian cartoonist, translated by Helge Dascher (without whom, I'm coming to think, a good half of the comics I like would never make it to America). I looked for this in a store several times, but eventually the hegemonic online retailer got my money. You snooze, you lose, small retailers.

The Delirium Brief by Charles Stross -- The new "Laundry Files" book, and the first from a new publisher (Tor.com, which is not the same as plain vanilla Tor but is shown as just Tor on the spine, for maximum confusion among publishing folks). I'm a big fan of this series, and will keep saying so loudly until they're huge bestsellers.

The Delirium Brief by Charles Stross -- The new "Laundry Files" book, and the first from a new publisher (Tor.com, which is not the same as plain vanilla Tor but is shown as just Tor on the spine, for maximum confusion among publishing folks). I'm a big fan of this series, and will keep saying so loudly until they're huge bestsellers.

All Systems Red by Martha Wells -- I've missed Wells's last few books -- pretty much the entire series about people with wings, which didn't entice me for some reason -- but I liked everything I read of hers before that. And this is both SF and short, which makes it intriguing. It's also about a robot that got self-awareness (or maybe self-direction) through a glitch and calls itself (secretly) Murderbot, which appeals to the John Sladek fan in me.

All Systems Red by Martha Wells -- I've missed Wells's last few books -- pretty much the entire series about people with wings, which didn't entice me for some reason -- but I liked everything I read of hers before that. And this is both SF and short, which makes it intriguing. It's also about a robot that got self-awareness (or maybe self-direction) through a glitch and calls itself (secretly) Murderbot, which appeals to the John Sladek fan in me.

And, when I buy "stuff," nearly all of it will be books. (I also got Beth Orton's newish record Kidsticks, which I haven't yet pulled out of the plastic and ripped to this computer. But I hear this one is more electronic, which should be fun.)

One of those books will take some time to get here. But the rest are here, and they are:

Giant Days: Not on the Test Edition, Vol. 1 by John Allison, Lissa Treiman and Max Sarin -- How can you know if a comics series will be popular enough to spawn a hardcover reprint series? It's maddening. In some cases (like Hellboy) the hardcovers start up twenty years after the paperbacks, so at least it doesn't feel like buying the same thing immediately afterward. Look, I'm happy to have these stories in a nicer hardcover, and more happy to have the first of Allison's three self-published stories included here. But I'd rather have bought this instead of the two paperbacks, not afterward. And comics' backwards publishing schedule makes that difficult.

Dragons: The Modern Infestation by Pamela Wharton Blanpied -- I read and bought this for the SFBC back in the day (I think I bought it), but I lost my copy in the flood. I want to read it again to see if it's still as weird and sly as I remember.

Dragons: The Modern Infestation by Pamela Wharton Blanpied -- I read and bought this for the SFBC back in the day (I think I bought it), but I lost my copy in the flood. I want to read it again to see if it's still as weird and sly as I remember. White Noise by Don DeLillo -- We all seem to be living in the free-floating anxiety of a DeLillo novel these days, so I've been thinking about this book a lot. I haven't read it since my big run through DeLillo in the late '90s, and, as you know Bob, that was a long time ago.

White Noise by Don DeLillo -- We all seem to be living in the free-floating anxiety of a DeLillo novel these days, so I've been thinking about this book a lot. I haven't read it since my big run through DeLillo in the late '90s, and, as you know Bob, that was a long time ago. Paul Up North by Michel Rabagliati -- The latest in the loose (and loosely autobiographical) series by a great Francophone Canadian cartoonist, translated by Helge Dascher (without whom, I'm coming to think, a good half of the comics I like would never make it to America). I looked for this in a store several times, but eventually the hegemonic online retailer got my money. You snooze, you lose, small retailers.

Paul Up North by Michel Rabagliati -- The latest in the loose (and loosely autobiographical) series by a great Francophone Canadian cartoonist, translated by Helge Dascher (without whom, I'm coming to think, a good half of the comics I like would never make it to America). I looked for this in a store several times, but eventually the hegemonic online retailer got my money. You snooze, you lose, small retailers. The Delirium Brief by Charles Stross -- The new "Laundry Files" book, and the first from a new publisher (Tor.com, which is not the same as plain vanilla Tor but is shown as just Tor on the spine, for maximum confusion among publishing folks). I'm a big fan of this series, and will keep saying so loudly until they're huge bestsellers.

The Delirium Brief by Charles Stross -- The new "Laundry Files" book, and the first from a new publisher (Tor.com, which is not the same as plain vanilla Tor but is shown as just Tor on the spine, for maximum confusion among publishing folks). I'm a big fan of this series, and will keep saying so loudly until they're huge bestsellers. All Systems Red by Martha Wells -- I've missed Wells's last few books -- pretty much the entire series about people with wings, which didn't entice me for some reason -- but I liked everything I read of hers before that. And this is both SF and short, which makes it intriguing. It's also about a robot that got self-awareness (or maybe self-direction) through a glitch and calls itself (secretly) Murderbot, which appeals to the John Sladek fan in me.

All Systems Red by Martha Wells -- I've missed Wells's last few books -- pretty much the entire series about people with wings, which didn't entice me for some reason -- but I liked everything I read of hers before that. And this is both SF and short, which makes it intriguing. It's also about a robot that got self-awareness (or maybe self-direction) through a glitch and calls itself (secretly) Murderbot, which appeals to the John Sladek fan in me.

Friday, July 28, 2017

How The Hell Did This Happen? by P.J. O'Rourke

You goddamn asshole, P.J. O'Rourke. You, of all people, have the unmitigated gall to title a book How The Hell Did This Happen? and then collect two hundred pages of your writings showing how it happened?

You did it, you fuckhead. You and a hundred other Republican pundits and a thousand Republican elected officials. You've systematically destroyed the ability of government to function, denigrated the character and skills of everyone who actually tried to make government function, and aggrandized an endless series of ever-more-reactionary lunatic slimeballs.

And now you're surprised that the greatest lunatic slimeball has succeeded, after you've been laying the ground for him for three decades? That dog won't hunt, Pat. You own this. This shitstorm has your fingerprints all over it, and trying to slither out by pretending you're a libertarian asshole, so you want to burn down the parts of the government that even the Republicans intend to keep...well, that's no excuse. You're standing there with a book of matches, shrugging your shoulders while the Republic burns? Fuck you.

O'Rourke's books have been getting lazier and more phoned-in for this entire century, if not longer, and How The Hell is solidly in that tradition: it's a fix-up of the political articles he wrote during the nearly two years of the 2016 campaign, edited a bit because the guy from O'Rourke's party won, and that turned out to be the worst possible outcome. (Oops!)

This allows him to edit out any predictions or ideas that turned out to be wrong, but he still engages in endless reams of partisan political bullshit. Just the most egregious example: Bernie Sanders is not a "socialist," and the O'Rourke of 1990 would have known that. I no longer trust that the contemporary one does; he's been drinking too much Kool-Aid for too long. And it's not like the Sanders platform wasn't built on rainbows and unicorn farts to begin with: there was plenty there for a self-professed libertarian to criticize if he wasn't lazily wasting all his time making second-coming-of-Stalin jokes.

Enough. How the Hell Did This Happen? is self-answering, for anyone even vaguely self-aware. He did it. He might even know he did it, on some level. But fuck if the prick will admit it.

If you're #NeverTrump and still a Republican -- which is harder and harder to do for anyone who can and does read, these days -- this book may validate your suffering. But it's really designed for the old white men like P.J.: the kind of rich assholes who are libertarian because that means lower taxes for them and they can pretend that slashing billions of dollars that help people less fortunate than them won't have any effect at all. The willfully blind, in short.

O'Rourke, you and your people did this. And you and your people are the only ones who can fix it right now. There is a mechanism to get rid of that turd in the punchbowl, an entirely Constitutional one, and it's well within the purview of your elected buddies. Don't come back until you've developed enough of a spine to admit your guilt and a willingness to call for the obvious solution.

Quote of the Week

"For example, the phrase 'I’ve spent a conflict-free life' is not something a person could honestly say if he had, in fact, taken a knife and killed two people with it. ...

"Although the full quote is worth raising at least one eyebrow at:

- Kevin Underhill, Lowering the Bar, explicating a deposition from one Orenthal James Simpson

"Although the full quote is worth raising at least one eyebrow at:

I’ve always thought I’d been pretty good with people and I basically have spent a conflict-free life. You know? I’m not a guy that ever got in a fight on the street and with the public and everybody…."Hm. Those are unusual qualifiers for somebody who’s never been in a conflict at all. Not 'on the street and with the public and everybody,' but … what? It almost seems to suggest he got in least one fight under other circumstances at some point. But he didn’t finish his sentence, so I guess we’ll never know."

- Kevin Underhill, Lowering the Bar, explicating a deposition from one Orenthal James Simpson

Thursday, July 27, 2017

Bad Machinery, Vol. 7: The Case of the Forked Road by John Allison

The Mystery Tweens are solidly becoming Mystery Teens in The Case of the Forked Road,

which means the boys have all seemingly lost 50 IQ points and keep

punching each other for no reason. [1] So any mystery solving will be

left to the girls, this time out.

Since this is a volume seven, before I go any further, there are two notes. First is that you don't need to know anything going into this book. Well, OK: these are kids in a secondary school in Tackleford, the oddest town in England. You can pick that up from the book, and it's all you need to know. Also, this is a collection of a webcomic, so you can always read as much of it as you want online.

But, if you do want to know more, let me direct you to my posts about Bad Machinery books one, two, three, four, five, and six. You may also be interested in the pre-Bad Machinery comic Scary Go Round, also set in Tackleford, which led to the comic-book format Giant Days, of which there have been several collections so far: one two three four.

The book version of The Case of the Forked Road, as usual, is slightly expanded from the webcomics version, with some pages redrawn a bit and others added to aid the flow. It also begins with a new page introducing the main characters and ends with several related old Scary Go Round pages -- both of those introduced and narrated by Charlotte Grote, Allison's current troublemaking smart-girl character (following a string of such in the past).

As usual, Allison is great at capturing speech patterns and the half-fascinated, half-oblivious attitude of teens -- the girls discover a mystery this time, in the suspicious activities of a elderly lab assistant they call "Grumpaw." But they have no idea what this guy's name is, and have to go through convolutions just to get their investigation started.

They do, of course, and eventually find a fantastical explanation to the question of Grumpaw and the mysterious and strangely ignorant schoolboy Calvin. And the dangers they have to deal with this time out are directly related to the stupid violence of some male classmates. (Though the cover shows that it's not the boy Mystery Teens; they stay offstage most of the time, and are useless when they're on it.)

Allison writes smart stories that wander interestingly through his story-space and gives his characters very funny, real dialogue to say on every page. And I think his stories are best when he draws them himself: his line is just as puckish and true as his writing. That makes the Bad Machinery cases the very best Allison books coming out now.

One last point: if you've complained that previous Bad Machinery volumes -- wide oblong shapes to show off the webcomic strips -- were physically problematic, then you are in luck. The Case of the Forked Road is laid out like normal comic-book-style pages, just as these strips appeared online. So you no longer have that excuse, and must, by law, buy Forked Road immediately.

[1] If you think this is some kind of sexist nonsense, my currently sixteen-year-old son can tell you a story of some of his fellow students on his recent trip to Germany and Italy. These young men got into trouble because they were throwing some "hot rocks" around -- as you do when you discover some rocks that are warmed by the sun, in a nice hotel in a foreign county -- until, inevitably, windows got broken. There are boys who avoid the Enstupiding and Masculinizing Ray of Puberty, but they are few and beleaguered, and the general effects of the ray hugely debilitating.

Since this is a volume seven, before I go any further, there are two notes. First is that you don't need to know anything going into this book. Well, OK: these are kids in a secondary school in Tackleford, the oddest town in England. You can pick that up from the book, and it's all you need to know. Also, this is a collection of a webcomic, so you can always read as much of it as you want online.

But, if you do want to know more, let me direct you to my posts about Bad Machinery books one, two, three, four, five, and six. You may also be interested in the pre-Bad Machinery comic Scary Go Round, also set in Tackleford, which led to the comic-book format Giant Days, of which there have been several collections so far: one two three four.

The book version of The Case of the Forked Road, as usual, is slightly expanded from the webcomics version, with some pages redrawn a bit and others added to aid the flow. It also begins with a new page introducing the main characters and ends with several related old Scary Go Round pages -- both of those introduced and narrated by Charlotte Grote, Allison's current troublemaking smart-girl character (following a string of such in the past).

As usual, Allison is great at capturing speech patterns and the half-fascinated, half-oblivious attitude of teens -- the girls discover a mystery this time, in the suspicious activities of a elderly lab assistant they call "Grumpaw." But they have no idea what this guy's name is, and have to go through convolutions just to get their investigation started.

They do, of course, and eventually find a fantastical explanation to the question of Grumpaw and the mysterious and strangely ignorant schoolboy Calvin. And the dangers they have to deal with this time out are directly related to the stupid violence of some male classmates. (Though the cover shows that it's not the boy Mystery Teens; they stay offstage most of the time, and are useless when they're on it.)

Allison writes smart stories that wander interestingly through his story-space and gives his characters very funny, real dialogue to say on every page. And I think his stories are best when he draws them himself: his line is just as puckish and true as his writing. That makes the Bad Machinery cases the very best Allison books coming out now.

One last point: if you've complained that previous Bad Machinery volumes -- wide oblong shapes to show off the webcomic strips -- were physically problematic, then you are in luck. The Case of the Forked Road is laid out like normal comic-book-style pages, just as these strips appeared online. So you no longer have that excuse, and must, by law, buy Forked Road immediately.

[1] If you think this is some kind of sexist nonsense, my currently sixteen-year-old son can tell you a story of some of his fellow students on his recent trip to Germany and Italy. These young men got into trouble because they were throwing some "hot rocks" around -- as you do when you discover some rocks that are warmed by the sun, in a nice hotel in a foreign county -- until, inevitably, windows got broken. There are boys who avoid the Enstupiding and Masculinizing Ray of Puberty, but they are few and beleaguered, and the general effects of the ray hugely debilitating.

Wednesday, July 26, 2017

Thinking in Pictures by Temple Grandin

I don't know about anyone else, but I very rarely read a book for just one reason. (It feels like I rarely do anything for just one reason.) Nothing is unmixed.

So I've been interested in Temple Grandin, the most famous and accomplished person with autism, for a while, because of what she accomplished and because of what she overcame. And, as the father of a son on the autism spectrum -- I think the current DSM collapsed all of the previous niche categories to "autism spectrum disorder" with explanations in individual cases -- I'm worried and interested and thrilled and confused by what that disorder means. (And I know that every person is a bit different, particularly in this area: the current medical category of "autism" covers a vast territory from "not great at personal interaction" to "completely non-verbal.")

Thinking in Pictures was Grandin's third book and her second to wrestle with the "who I am and how I got to where I am" question, after her first book Emergence: Labeled Autistic. And I believe this is generally seen as the Grandin book to read or start with -- unless you're engaging with her on a professional level, obviously, in which case you'd look at her technical publications -- so it was the one I picked up.

It's something like an autobiography and something like a book about how her mind works differently than those of neurotypical people and something like a book about how to understand and deal with people with autism. Grandin organized the book into eleven thematic chapters, each more-or-less about how autism affects one aspect of her life -- and the lives of others, informed by research. Grandin is a scholar, so she has citations of the kind suitable for a mass-audience book -- you could follow them, if you really wanted to. Since the book is twenty years old, and the study of autism still a young field, I expect the landscape has changed quite a bit since then, though.

Grandin follows connections between topics within those chapters, and those connections may not be the ones neurotypical people will expect. I'd call that a feature rather than a bug: the point of Thinking in Pictures is to give us a view of how Grandin thinks through things, and it also gives us a glimpse of what it might be like for an autistic person to live in a world with people who think neurotypically.

I do think things have changed, in treatment options and definitely in categorization, since Grandin wrote Thinking in Pictures. So those sections and references may be less useful these days, particularly to families dealing with an initial diagnosis of autism for a child. (Autism is defined as a developmental disorder: it has to be diagnosed in childhood, and usually, these days, is identified before school age.) But her life is still what it was, and her insights and ability to describe how she thinks are as useful and illuminating as ever.

I tend to think we all think more differently from each other than we generally admit -- that "the spectrum" (as in autism) is part of a much wider spectrum, extending out multi-dimensionally. So the fact that any one of us is not diagnosed with autism doesn't mean we're "normal" -- it just means we think in ways that haven't caused this particular kind of problem yet, or that our differences are less diagnose-able, or just that we're functional enough that it's not worth the resources to investigate us. But understanding, in any ways we can, how other people think can only be helpful. And Thinking in Pictures is a marvelous look into one particular way of thinking, by one very accomplished and introspective woman.

So I've been interested in Temple Grandin, the most famous and accomplished person with autism, for a while, because of what she accomplished and because of what she overcame. And, as the father of a son on the autism spectrum -- I think the current DSM collapsed all of the previous niche categories to "autism spectrum disorder" with explanations in individual cases -- I'm worried and interested and thrilled and confused by what that disorder means. (And I know that every person is a bit different, particularly in this area: the current medical category of "autism" covers a vast territory from "not great at personal interaction" to "completely non-verbal.")

Thinking in Pictures was Grandin's third book and her second to wrestle with the "who I am and how I got to where I am" question, after her first book Emergence: Labeled Autistic. And I believe this is generally seen as the Grandin book to read or start with -- unless you're engaging with her on a professional level, obviously, in which case you'd look at her technical publications -- so it was the one I picked up.

It's something like an autobiography and something like a book about how her mind works differently than those of neurotypical people and something like a book about how to understand and deal with people with autism. Grandin organized the book into eleven thematic chapters, each more-or-less about how autism affects one aspect of her life -- and the lives of others, informed by research. Grandin is a scholar, so she has citations of the kind suitable for a mass-audience book -- you could follow them, if you really wanted to. Since the book is twenty years old, and the study of autism still a young field, I expect the landscape has changed quite a bit since then, though.

Grandin follows connections between topics within those chapters, and those connections may not be the ones neurotypical people will expect. I'd call that a feature rather than a bug: the point of Thinking in Pictures is to give us a view of how Grandin thinks through things, and it also gives us a glimpse of what it might be like for an autistic person to live in a world with people who think neurotypically.

I do think things have changed, in treatment options and definitely in categorization, since Grandin wrote Thinking in Pictures. So those sections and references may be less useful these days, particularly to families dealing with an initial diagnosis of autism for a child. (Autism is defined as a developmental disorder: it has to be diagnosed in childhood, and usually, these days, is identified before school age.) But her life is still what it was, and her insights and ability to describe how she thinks are as useful and illuminating as ever.

I tend to think we all think more differently from each other than we generally admit -- that "the spectrum" (as in autism) is part of a much wider spectrum, extending out multi-dimensionally. So the fact that any one of us is not diagnosed with autism doesn't mean we're "normal" -- it just means we think in ways that haven't caused this particular kind of problem yet, or that our differences are less diagnose-able, or just that we're functional enough that it's not worth the resources to investigate us. But understanding, in any ways we can, how other people think can only be helpful. And Thinking in Pictures is a marvelous look into one particular way of thinking, by one very accomplished and introspective woman.

Tuesday, July 25, 2017

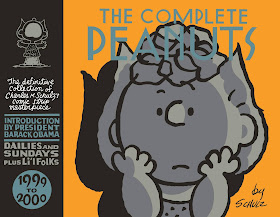

The Complete Peanuts, Vol. 26 by Charles M. Schulz

This time, it definitely is the end. The previous volume finished up reprinting the fifty-year [1] run of Charles M. Schulz's comic strip Peanuts in twenty-five volumes, two years in each book. (See my posts on nearly all of those books: 1957-1958, 1959-1960, 1961-1962, 1963-1964, 1965-1966, 1967-1968, 1969-1970, 1971-1972, 1973-1974, 1975-1976, 1977-1978, 1979-1980, 1981-1982, 1983-1984, 1985-1986, 1987-1988, 1989-1990, 1991-1992, 1993-1994, the flashback to 1950-1952, 1995-1996, 1997-1998, and finally 1999-2000.)

Vol. 26 does something slightly different: it collects related works. It has comic book pages and advertising art and gift-sized books (some of which could be called "graphic novels," with only a tiny bit of squinting) and similar things -- all featuring the Peanuts characters, all written and drawn by Schulz. Obviously, this was culled from a far larger mass of related Peanuts stuff -- dozens of hours of TV specials, to begin with, plus major ad campaigns for many products over most of those fifty years, among other things -- but Schulz managed and supervised and oversaw (or just licensed and approved) the vast majority of those.

This book has just the art and words that can be attributed cleanly to Schulz personally. Not all of it -- there's plenty of other spot illustrations, and a number of other small cash-grab gift books, that Fantagraphics could have included if they wanted to be comprehensive, but they didn't. Instead, this is a book about the size of the others, that will sit next to them on a shelf and complement them.

Annoyingly, this very miscellaneous book avoids a table of contents -- possibly because the previous books didn't need one? -- so you discover things one by one as you read it. It starts off with seventeen gag cartoons that Schulz sold to the Saturday Evening Post in the late '40s, featuring kid characters much like the ones in L'il Folks and so somewhere in the parentage of Peanuts. Next up is seven comic-book format stories from the late '50s that Jim Sasseville (from Schulz's studio at the time) has identified as all-Schulz (among a much, much larger body of comic-book stories that I think were mostly by Sasseville). These are interesting, because they show Schulz with a larger palette (both physically and story-wise) than a four-panel comic strip -- he still mostly keeps to a rigid grid, but there's more energy in his layouts and he has room for better back-and-forth dialogue in multi-page stories.

Then there's a section of advertising art, which begins with five pages of camera-themed strips that appeared in 1955's The Brownie Book of Picture-Taking from Kodak but quickly turns into obvious ads for the Ford Falcon and Interstate Bakeries. The latter two groups are intermittently amusing, but mostly show that Peanuts characters were actively shilling for stuff a few decade before most of us realized it.

The book moves back into story-telling with three Christmas stories, which all originally appeared in women's magazines from 1958 through 1968 (at precisely five-year intervals -- what stopped the inevitable 1973 story?). The first one is two Sunday-comics-size pages; the others are a straight series of individual captioned pictures in order. After that comes four of the little gift books -- two about Snoopy and the Red Baron, two about Snoopy and his literary career -- which adapt and expand on gags and sequences from the main strip. (I recently tracked down and read the one about Snoopy's magnum opus, which I still have a lot of fondness for.)

Two more little gift books follow, these more obviously cash-grabs: Things I Learned After It Was Too Late and it's follow-up, from the early '80s. These were cute-sayings books, with pseudo-profound thoughts each placed carefully on a small page with an appropriate drawing. Schulz's pseudo-profound thoughts are as good as anyone's, I suppose.

Last from Sparky are a series of drawings and gags about golf and tennis, the two sports most obviously important to him -- we already knew that from the strip itself. The golf stuff is very much for players of the game, and possibly even more so for players of the game in the '60s and '70s, but at least some of the gags will hit for non-golfers several decades later. The tennis material is slightly newer, and slightly less insider-y, and so it has dated a little less.

The book is rounded out by a long afterword by Schulz's widow, Jean Schulz. It provides a personal perspective, but takes up a lot of space and mostly serves to show that Jean loved and respected her husband. That's entirely a positive thing, but I'm not 100% convinced it required twenty-four pages of type in a book of comics and drawings.

Vol. 26 is a book for those of us who bought the first twenty-five; no one is going to start here. And, for us, it's a great collection of miscellaneous stuff. Some of us will like some of it better than others, but every Peanuts fan will find some things in here to really enjoy.

[1] OK, a few months shy of actually fifty years -- it started in October 1950 and ended in February 2000. But that's close enough for most purposes.

Vol. 26 does something slightly different: it collects related works. It has comic book pages and advertising art and gift-sized books (some of which could be called "graphic novels," with only a tiny bit of squinting) and similar things -- all featuring the Peanuts characters, all written and drawn by Schulz. Obviously, this was culled from a far larger mass of related Peanuts stuff -- dozens of hours of TV specials, to begin with, plus major ad campaigns for many products over most of those fifty years, among other things -- but Schulz managed and supervised and oversaw (or just licensed and approved) the vast majority of those.

This book has just the art and words that can be attributed cleanly to Schulz personally. Not all of it -- there's plenty of other spot illustrations, and a number of other small cash-grab gift books, that Fantagraphics could have included if they wanted to be comprehensive, but they didn't. Instead, this is a book about the size of the others, that will sit next to them on a shelf and complement them.

Annoyingly, this very miscellaneous book avoids a table of contents -- possibly because the previous books didn't need one? -- so you discover things one by one as you read it. It starts off with seventeen gag cartoons that Schulz sold to the Saturday Evening Post in the late '40s, featuring kid characters much like the ones in L'il Folks and so somewhere in the parentage of Peanuts. Next up is seven comic-book format stories from the late '50s that Jim Sasseville (from Schulz's studio at the time) has identified as all-Schulz (among a much, much larger body of comic-book stories that I think were mostly by Sasseville). These are interesting, because they show Schulz with a larger palette (both physically and story-wise) than a four-panel comic strip -- he still mostly keeps to a rigid grid, but there's more energy in his layouts and he has room for better back-and-forth dialogue in multi-page stories.

Then there's a section of advertising art, which begins with five pages of camera-themed strips that appeared in 1955's The Brownie Book of Picture-Taking from Kodak but quickly turns into obvious ads for the Ford Falcon and Interstate Bakeries. The latter two groups are intermittently amusing, but mostly show that Peanuts characters were actively shilling for stuff a few decade before most of us realized it.

The book moves back into story-telling with three Christmas stories, which all originally appeared in women's magazines from 1958 through 1968 (at precisely five-year intervals -- what stopped the inevitable 1973 story?). The first one is two Sunday-comics-size pages; the others are a straight series of individual captioned pictures in order. After that comes four of the little gift books -- two about Snoopy and the Red Baron, two about Snoopy and his literary career -- which adapt and expand on gags and sequences from the main strip. (I recently tracked down and read the one about Snoopy's magnum opus, which I still have a lot of fondness for.)

Two more little gift books follow, these more obviously cash-grabs: Things I Learned After It Was Too Late and it's follow-up, from the early '80s. These were cute-sayings books, with pseudo-profound thoughts each placed carefully on a small page with an appropriate drawing. Schulz's pseudo-profound thoughts are as good as anyone's, I suppose.

Last from Sparky are a series of drawings and gags about golf and tennis, the two sports most obviously important to him -- we already knew that from the strip itself. The golf stuff is very much for players of the game, and possibly even more so for players of the game in the '60s and '70s, but at least some of the gags will hit for non-golfers several decades later. The tennis material is slightly newer, and slightly less insider-y, and so it has dated a little less.

The book is rounded out by a long afterword by Schulz's widow, Jean Schulz. It provides a personal perspective, but takes up a lot of space and mostly serves to show that Jean loved and respected her husband. That's entirely a positive thing, but I'm not 100% convinced it required twenty-four pages of type in a book of comics and drawings.

Vol. 26 is a book for those of us who bought the first twenty-five; no one is going to start here. And, for us, it's a great collection of miscellaneous stuff. Some of us will like some of it better than others, but every Peanuts fan will find some things in here to really enjoy.

[1] OK, a few months shy of actually fifty years -- it started in October 1950 and ended in February 2000. But that's close enough for most purposes.

Monday, July 24, 2017

Reviewing the Mail: Week of 7/22

You know, quite frankly I'm often surprised I get any books in the mail these days. It's no longer 2011, and I was never very big as a blogger to begin with. (And I tend to ignore publicists when they try to contact me, which is not the way to ingratiate yourself to them -- I can tell you that much for free.)

So this weekly post has been getting shorter and less frequent for years now, in a long withdrawing Dover Beach stylee.

That's my excuse for this week, at least -- I have no books to tell you about this time, and this is the stake in the ground I'm carefully placing to tell you why. I'll be back next week, possibly with a different excuse. (Collect them all!)

So this weekly post has been getting shorter and less frequent for years now, in a long withdrawing Dover Beach stylee.

That's my excuse for this week, at least -- I have no books to tell you about this time, and this is the stake in the ground I'm carefully placing to tell you why. I'll be back next week, possibly with a different excuse. (Collect them all!)

Friday, July 21, 2017

Lost and Found: 1969-2003 by Bill Griffith

If you keep going long enough in a creative field, eventually someone

will collect your stuff. If you're reasonably successful, they'll even

collect the oddball stuff -- the one-offs and blind alleys and test-beds

and experiments that you made as you were working towards (or in

between) the works that you were better known for.

Yes, you too can be the proud creator of an odds and sods collection, if you live long enough and work hard enough and get lucky enough. If your name is Bill Griffith, congratulations! That book was published by Fantagraphics in 2011 as Lost and Found: 1969-2003.

Griffith has spent most of his career aiming his Zippy the Pinhead character, and associated folks, at whatever Griffith's current obsessions were. It's a good model for a cartoonist, actually: if you have a malleable character that you own, and a flexible, large cast around him, you can keep producing work that gives your audience continuity while telling the stories and working with the ideas you really want to in that moment. It's not coincidental that the major outlet for Zippy stories for the last three or four decades has been a syndicated comic strip: that's been the model for a huge number of successful comics creators for over a century, a way to reach a large audience with work that can, for the right person, be personal and idiosyncratic.

But that's what's not in this book. It has one sequence from the Zippy strip, but it's mostly comic-book-formatted pages, and it's mostly from anthologies and magazines and other people's comics -- the stuff he was doing when he wasn't making Zippy strips and purely Zippy comic-books.

Zippy's in a lot, though. Griffith developed his cast early, and has used them across all of his cartooning formats. But he's definitely not as central here as he is in most of Griffith's work. Lost and Found is heavily weighted towards the early part of Griffith's career -- the 1970s is by far the largest section -- and so this is a book in large part showing how that cast first appeared and developed.

Mr. Toad was the original central character in Griffith's stories, starting off as an Everyman type but quickly becoming the raging id (loosely modeled on Griffith's father, as he acknowledges later in this book) he was meant to be. So he's the first main character the reader meets, soon accompanied by some one-off folks from Young Lust (the sex-filled parody of romance comics that Griffith co-edited).

Frankly, the early comics are very "underground" -- rambling and navel-gazing in turn, clearly drawn by someone who is still learning his craft and doesn't have any strong models or guidelines for what he's doing. To be more pointed, they're not very good. They're interesting for people who like the mature Zippy stuff -- you can trace the development of Claude Funston pretty clearly, and obviously The Toad -- but the first hundred pages of Lost and Found is a bit of a slog for anyone not already seeped in '60s counterculture.

(As they say, if you can remember the '60s, you weren't there. I don't remember them, but I wasn't there, either.)

The back half of Lost and Found is more impressive, with one-off stories set in the Zippy universe that appeared various places during the '80s and '90s, including an extensive color section. This is the part of Lost and Found that most readers will be looking for: I almost recommend that folks start here, and only dip back into the '70s section randomly as they have the inclination. (I don't actually recommend that, because I'm a fiend for doing things in the right order.)

But, again: this is an odds and sods collection. There will always be sods. It's the nature of the beast. You gotta take them with the odds. And some of this is quite odd.

Yes, you too can be the proud creator of an odds and sods collection, if you live long enough and work hard enough and get lucky enough. If your name is Bill Griffith, congratulations! That book was published by Fantagraphics in 2011 as Lost and Found: 1969-2003.

Griffith has spent most of his career aiming his Zippy the Pinhead character, and associated folks, at whatever Griffith's current obsessions were. It's a good model for a cartoonist, actually: if you have a malleable character that you own, and a flexible, large cast around him, you can keep producing work that gives your audience continuity while telling the stories and working with the ideas you really want to in that moment. It's not coincidental that the major outlet for Zippy stories for the last three or four decades has been a syndicated comic strip: that's been the model for a huge number of successful comics creators for over a century, a way to reach a large audience with work that can, for the right person, be personal and idiosyncratic.

But that's what's not in this book. It has one sequence from the Zippy strip, but it's mostly comic-book-formatted pages, and it's mostly from anthologies and magazines and other people's comics -- the stuff he was doing when he wasn't making Zippy strips and purely Zippy comic-books.

Zippy's in a lot, though. Griffith developed his cast early, and has used them across all of his cartooning formats. But he's definitely not as central here as he is in most of Griffith's work. Lost and Found is heavily weighted towards the early part of Griffith's career -- the 1970s is by far the largest section -- and so this is a book in large part showing how that cast first appeared and developed.

Mr. Toad was the original central character in Griffith's stories, starting off as an Everyman type but quickly becoming the raging id (loosely modeled on Griffith's father, as he acknowledges later in this book) he was meant to be. So he's the first main character the reader meets, soon accompanied by some one-off folks from Young Lust (the sex-filled parody of romance comics that Griffith co-edited).

Frankly, the early comics are very "underground" -- rambling and navel-gazing in turn, clearly drawn by someone who is still learning his craft and doesn't have any strong models or guidelines for what he's doing. To be more pointed, they're not very good. They're interesting for people who like the mature Zippy stuff -- you can trace the development of Claude Funston pretty clearly, and obviously The Toad -- but the first hundred pages of Lost and Found is a bit of a slog for anyone not already seeped in '60s counterculture.

(As they say, if you can remember the '60s, you weren't there. I don't remember them, but I wasn't there, either.)

The back half of Lost and Found is more impressive, with one-off stories set in the Zippy universe that appeared various places during the '80s and '90s, including an extensive color section. This is the part of Lost and Found that most readers will be looking for: I almost recommend that folks start here, and only dip back into the '70s section randomly as they have the inclination. (I don't actually recommend that, because I'm a fiend for doing things in the right order.)

But, again: this is an odds and sods collection. There will always be sods. It's the nature of the beast. You gotta take them with the odds. And some of this is quite odd.

Thursday, July 20, 2017

The Summit of the Gods, Vol. 1 by Yumemakura Baku and Jiro Taniguchi

Wanna know a secret? I really don't give a shit about mountain climbing. Very few people do. Very few people give a shit about any

random pastime you could name -- shuffleboard, mate-swapping,

parasailing, Yahtzee, building boats in bottles -- either as a

participant or a spectator.

But sometimes we can be made to care, through the power of art.

And that's how I came to The Summit of the Gods, Vol. 1, the first of a five-volume series about Japanese mountain climbers written by Yumemakura Baku and drawn by Jiro Taniguchi. Well, to be more honest, I came to it because I'd read Taniguichi's two-book series A Distant Neighborhood (see my posts on books one and two), and wanted more Taniguchi. I'd neglected to read the fine print, and hadn't realized that Taniguchi was just contributing his picture-making abilities here, not his writing-stories skills.

(There are people who follow artists around comics. I've even been one of them, once in a while. But I'm mainly interested in story, and I mainly follow people who tell stories. So when a writer-artist I like starts just writing, it may be a bit sad, but I'm generally happy. If he starts just drawing, it's a huge calamity.)

Baku is a good story-teller, and he makes some interesting complex characters here. His main character is both a world-class asshole and a deeply compelling protagonist, which is a tough thing to pull off. He's also telling a long story with grace and ease -- it looks like the whole five-volume series is a single, complete story, and I like seeing people who can do that well.

But, frankly, I still don't give a shit about mountain climbing. I thought The Summit of the Gods would make me care, at least for the length of time to read the book. But, as it turned out, it didn't. The pictures are breathtaking and the people are real, but this is just not a story that I ended up caring about. It's certainly a flaw on my part, and no reflection on the book.

But I don't expect to go back for the later volumes, and I can say definitively that climbing mountains is something I will never give a shit about. As I get older, having those signposts are more and more useful, to mark off all of the things I don't have to explore any more, since they've bored me enough already. I recommend that feeling highly, whatever the things you decide you personally don't give a shit about.

But sometimes we can be made to care, through the power of art.

And that's how I came to The Summit of the Gods, Vol. 1, the first of a five-volume series about Japanese mountain climbers written by Yumemakura Baku and drawn by Jiro Taniguchi. Well, to be more honest, I came to it because I'd read Taniguichi's two-book series A Distant Neighborhood (see my posts on books one and two), and wanted more Taniguchi. I'd neglected to read the fine print, and hadn't realized that Taniguchi was just contributing his picture-making abilities here, not his writing-stories skills.

(There are people who follow artists around comics. I've even been one of them, once in a while. But I'm mainly interested in story, and I mainly follow people who tell stories. So when a writer-artist I like starts just writing, it may be a bit sad, but I'm generally happy. If he starts just drawing, it's a huge calamity.)

Baku is a good story-teller, and he makes some interesting complex characters here. His main character is both a world-class asshole and a deeply compelling protagonist, which is a tough thing to pull off. He's also telling a long story with grace and ease -- it looks like the whole five-volume series is a single, complete story, and I like seeing people who can do that well.

But, frankly, I still don't give a shit about mountain climbing. I thought The Summit of the Gods would make me care, at least for the length of time to read the book. But, as it turned out, it didn't. The pictures are breathtaking and the people are real, but this is just not a story that I ended up caring about. It's certainly a flaw on my part, and no reflection on the book.

But I don't expect to go back for the later volumes, and I can say definitively that climbing mountains is something I will never give a shit about. As I get older, having those signposts are more and more useful, to mark off all of the things I don't have to explore any more, since they've bored me enough already. I recommend that feeling highly, whatever the things you decide you personally don't give a shit about.

Wednesday, July 19, 2017

Hawkeye, Vol. 3: L.A. Woman by Fraction, Wu, Pulido, and others

Last month, I read a book called Hawkeye, Vol. 1. This month, I hit one called Vol. 3. In the annoyingly typical way of Big Two comics, the latter follows directly from the former. (One is a hardcover, which in comics-reprinting circles comes typically a year or two after the paperback and combines two paperbacks together. Yes, that's the opposite of how we old-time book-industry hands are used to seeing things happen, but it seems to work for the Wednesday Crowd.)

Anyway, at the end of Vol. 1, the two Hawkeyes split up, because comics are all about break-ups and changes and new things that can last for six issues or so. (Spider-Man No More! once again.) L.A. Woman follows the younger female Hawkeye, Kate Bishop, who drives a cool car cross country to the city of the title, where she immediately gets caught up in nefarious doings and skulduggery of her own. Presumably there's a Vol. 4 that features what Hawkguy was doing at the same time back in NYC, and that seems to be about as long as this particular set-up ran.

Kate's travails form yet another "gritty" and "realistic" superhero comic -- no powers, no flying, more-or-less the real world -- that descends from the Miller/Mazzuchelli "Born Again" run in Daredevil, the major cliche in this area. Look, comics folks, we all know it's not hard to put a bullet in someone's head. And people without superpowers who repeatedly annoy large-scale criminals without actually jailing those criminals find themselves possessors of those bullets-in-the-head sooner rather than later. So talking-killer scenes, and repeated hairsbreadth escapes in noirish colors, just lampshade how artificial your story is. Avoid them. If your villain isn't going to actually try to kill the hero like an actual criminal would in a real world, don't go down that road and pretend that the plan is to kill her. We all know that's not the case.

Speaking of which...Kate runs afoul of a supervillain carefully tailored to her abilities, one who can stymie her and cause her great pain but not blow her away instantly or hire goons to kidnap and murder her family by the snap of her fingers. So she's in L.A., and she Loses Everything.

That's OK, comics characters Lose Everything roughly once a year -- it's one of their major shticks. But she's young and a fairly new character, so this is one of her first Lose Everythings, and it has that element of novelty to it.

By the end of this book, she's Voluntarily Relinquished Everything -- the next step towards Getting Everything Back, And Even Better, Because She's The Good Guy -- and is heading off for the vengeance and catharsis that probably got sidetracked and muted by some stupid crossover or other.

These are good superhero comics, for all that they're drenched in cliches. It's not quite as good as the Clint Barton stuff in the earlier issues, maybe because he's easier to make a sad-sack in the first place. But "good superhero comics" is perilously close to damning with faint praise, along the lines of "a perfectly serviceable category Regency." I wish readers and creators could aim higher, but that's life.

If you like stories about superheroes who can't jump over buildings with a single bound, and like to pretend that such people are "realistic," you will probably enjoy the stories that Matt Fraction wrote about the various Hawkeyes. This time out, the opening story is drawn by Javier Pulido and the rest by Annie Wu, who are both good at the moderately gritty, real-people thing in their own ways. Go for it: I can't stop you.

Tuesday, July 18, 2017

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters by Emil Ferris

Karen Reyes is ten years old in 1968, and she loves monsters. Monster

movies, monster magazines, the idea of monsters -- imagining that there

are real monsters around her in her normal Chicago life. She's also

seriously bullied and outcast, with no real close friends as the book

begins. And she's telling us her own story, drawing it page-by-page in a series of notebooks, with herself as a kid-werewolf PI in fedora and

trenchcoat.

But My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is not cute. And it's also not the kind of book where the reader understands the truth of what's opaque to the narrator, like The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. Karen is young, and there's a lot of things she doesn't know, and she does want to become a movie-monster, but she's mostly clear-eyed about the world around her, and she's good at finding things out and piecing things together. (She will make a good detective when she grows up.)

And her upstairs neighbor, Anka Silverberg, did just die -- shot in the heart in her living room, though found dead in her bed. Since the apartment was locked at the time, the police have closed the case quickly as a suicide. But Anka has deep secrets from her life in Berlin before and during WW II -- and she's not the only one with secrets in the building, from her musician husband to the minor-gangster landlord and his hot-to-trot-wife, to the ventriloquist in the basement and Karen's twenty-something amateur-gigolo brother Deez and hillbilly mother.

Karen does meet some other kids who she sees as monsters, or possible monsters. And one of those may not be entirely a real person who actually exists in the world. So there's some unreliable-narrator elements, or fabulist elements, in the mix as well. But, at her core, Karen is honest and straightforward: she's trying to find out the truth, and has some good tools for doing so.

The truth -- which doesn't all come out in this book, the first of at least two -- looks to be bigger and more dangerous and complicated than one ten-year-old girl can fix. And her family has clearly been trying to keep some big secrets from her, like Deez's relationship with Anka.

I've tagged this book as "Fantasy," but I don't think it really is. But it's a book about the fantasies that we have, and about how fantasy creatures can make real life bearable.

All that is told as if drawn by Karen -- don't think too hard about when she has the time to draw this much, or how she got this good at the age of ten -- in colored pens on pages lined in blue, to mimic a notebook. There's around five hundred of those pages, though none of them are numbered, and there are a lot of words on many of these large pages. My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is a big book in every way: physically large, full of words, impressive pictorially, challenging in subject matter and storytelling.

This is Emil Ferris's first book -- she's a woman about the age Karen Reyes would be, grown up, and she seems to have been a kid like Karen back in the late '60s. I have no idea how many of the elements of Monsters came out of Ferris's own life, real or transmuted over time, but I can say that Monsters is nothing like a memoir. It is a fully-formed story, about a deeply individual young woman, stuck in a bad situation -- several bad situations, overlapping -- and trying to cope with it through intellect and rational thought and just a bit of wishing.

It's a very impressive graphic novel. Several dozen more influential people have said that before me, and they're all very right. Debuts like this don't come around very often. This is something very special.

But My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is not cute. And it's also not the kind of book where the reader understands the truth of what's opaque to the narrator, like The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. Karen is young, and there's a lot of things she doesn't know, and she does want to become a movie-monster, but she's mostly clear-eyed about the world around her, and she's good at finding things out and piecing things together. (She will make a good detective when she grows up.)

And her upstairs neighbor, Anka Silverberg, did just die -- shot in the heart in her living room, though found dead in her bed. Since the apartment was locked at the time, the police have closed the case quickly as a suicide. But Anka has deep secrets from her life in Berlin before and during WW II -- and she's not the only one with secrets in the building, from her musician husband to the minor-gangster landlord and his hot-to-trot-wife, to the ventriloquist in the basement and Karen's twenty-something amateur-gigolo brother Deez and hillbilly mother.

Karen does meet some other kids who she sees as monsters, or possible monsters. And one of those may not be entirely a real person who actually exists in the world. So there's some unreliable-narrator elements, or fabulist elements, in the mix as well. But, at her core, Karen is honest and straightforward: she's trying to find out the truth, and has some good tools for doing so.

The truth -- which doesn't all come out in this book, the first of at least two -- looks to be bigger and more dangerous and complicated than one ten-year-old girl can fix. And her family has clearly been trying to keep some big secrets from her, like Deez's relationship with Anka.

I've tagged this book as "Fantasy," but I don't think it really is. But it's a book about the fantasies that we have, and about how fantasy creatures can make real life bearable.

All that is told as if drawn by Karen -- don't think too hard about when she has the time to draw this much, or how she got this good at the age of ten -- in colored pens on pages lined in blue, to mimic a notebook. There's around five hundred of those pages, though none of them are numbered, and there are a lot of words on many of these large pages. My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is a big book in every way: physically large, full of words, impressive pictorially, challenging in subject matter and storytelling.

This is Emil Ferris's first book -- she's a woman about the age Karen Reyes would be, grown up, and she seems to have been a kid like Karen back in the late '60s. I have no idea how many of the elements of Monsters came out of Ferris's own life, real or transmuted over time, but I can say that Monsters is nothing like a memoir. It is a fully-formed story, about a deeply individual young woman, stuck in a bad situation -- several bad situations, overlapping -- and trying to cope with it through intellect and rational thought and just a bit of wishing.

It's a very impressive graphic novel. Several dozen more influential people have said that before me, and they're all very right. Debuts like this don't come around very often. This is something very special.

Monday, July 17, 2017

Reviewing the Mail: Week of 7/15

Dateline: Sunday, 6 PM

I've just spent the day driving up and back to my great-aunt's assisted living facility in lovely Albany, NY (land of my birth), to gather furniture and move it to various places. I'm hot, tired, and in no mood for any of your shenanigans.

All right, so let's look at what books the Publicity Gods have given me this week -- am I going to have to spend the next hour looking for interesting things to say about books?

Scanning: no new books found

OK, we're done for the week. See you here next week for whatever may have arrived in the meantime. And, with any luck, other posts in between.

I've just spent the day driving up and back to my great-aunt's assisted living facility in lovely Albany, NY (land of my birth), to gather furniture and move it to various places. I'm hot, tired, and in no mood for any of your shenanigans.

All right, so let's look at what books the Publicity Gods have given me this week -- am I going to have to spend the next hour looking for interesting things to say about books?

Scanning: no new books found

OK, we're done for the week. See you here next week for whatever may have arrived in the meantime. And, with any luck, other posts in between.

Thursday, July 13, 2017

Princess Decomposia and Count Spatula by Andi Watson

This is, I think, still the most recent book by the excellent cartoonist Andi Watson, which I reviewed in a monthly round-up barely two years ago. Why did I read it again? Well, I think

that the first time around, I read it from an electronic copy, so I

eventually bought a real book for myself and took the opportunity to

read it again before placing it on the shelf.

Now, it's entirely possible that I already have a copy on the shelf, since my sense of what books I own and don't was completely blown to hell by my flood in 2011. I frankly can't remember what I used to have and got flooded out, and what I used to have and still have by a fluke, and what I was meaning to buy back then but never did, and what I was meaning to buy back then and did later, and what I've bought since then but haven't read, and what I've bought since then and read and forgot because I didn't care about it. This sucks, since I used to be really good at remembering all those things.

But being surprised by your own shelves is no bad thing, so I'm not actually complaining. Even if I have bought several books a couple of times over the past few years.

And if it means I read a cute little souffle like Princess Decomposia and Count Spatula again, even if I don't "need to," well, that still sounds like a good thing, doesn't it?

Go see my old post if you want to know anything about the book: it's by one of our great cartoonists, and it's suitable for middle-grade readers though not limited to them. That's good enough for me.

Now, it's entirely possible that I already have a copy on the shelf, since my sense of what books I own and don't was completely blown to hell by my flood in 2011. I frankly can't remember what I used to have and got flooded out, and what I used to have and still have by a fluke, and what I was meaning to buy back then but never did, and what I was meaning to buy back then and did later, and what I've bought since then but haven't read, and what I've bought since then and read and forgot because I didn't care about it. This sucks, since I used to be really good at remembering all those things.

But being surprised by your own shelves is no bad thing, so I'm not actually complaining. Even if I have bought several books a couple of times over the past few years.

And if it means I read a cute little souffle like Princess Decomposia and Count Spatula again, even if I don't "need to," well, that still sounds like a good thing, doesn't it?

Go see my old post if you want to know anything about the book: it's by one of our great cartoonists, and it's suitable for middle-grade readers though not limited to them. That's good enough for me.

Wednesday, July 12, 2017

UIniversal Harvester by John Darnielle

John Darnielle came to novel-writing late, after a long, and still flourishing, career as a songwriter and performer. He's been the central force, and occasionally the only member, of The Mountain Goats for nearly thirty years now.

John Darnielle came to novel-writing late, after a long, and still flourishing, career as a songwriter and performer. He's been the central force, and occasionally the only member, of The Mountain Goats for nearly thirty years now.And the assumption always is, when someone famous from another loosely-related creative endeavor decides to write a novel, that it's some kind of vanity project. But Darnielle is the real deal -- he took a detour to get to the novelist's chair, but he's been trying to get there his whole life. And he deeply belongs there.

Darnielle has followed up his excellent first novel Wolf in White Van with this year's equally slim and powerful Universal Harvester, showing that he's not just a guy who happened to write a novel (we all have one in us, right?) but a bona fide novelist.

This may be a spoiler, but Universal Harvester is not a horror novel. (At least, not in the Stephen King sense.) For a long time, it looks like it might be -- there's an atmosphere of looming ominousness, of unknown things going on in the background that may be deeply horrible when they're fully known.

And, you know, a lot of life is deeply horrible when it's fully known. Just this morning, I read a story in the paper of a man right about my age killed on a local highway. He'd stopped, carefully, on the shoulder, to adjust cargo on his car. Another car careened across several lanes to smash into his stopped car, killing him instantly. Witnesses described the crash as so violent that both cars "flew up into the air and spun around." Passers-by saved the elderly driver who caused the crash and her passengers with only minor injuries; a woman traveling with the dead man had to be life-flighted to a hospital, and is still in bad condition. That's just one example: death and pain and destruction lurk around every corner, and the people who are responsible so often skate on blithely while the people around them pay the price.

That car crash was a Mountain Goats song, or could have been.

Universal Harvester has a crash crash in it, but a smaller one, not as pyrotechnic and impressive. Maybe that's because the novel is set in a patchwork of small towns and farmlands around Nevada, Iowa, and for a big, impressive crash you need a multi-lane highway to give you both high speed and a lot of witnesses. The horrible things in Universal Harvester are smaller and more personal -- things that happen to you and your family in private. The things you don't share with outsiders, because they'll never understand.

Perhaps I should mention that there's another car crash -- one that happens before the novel opens. That's probably the most horrible thing here. But it's an Iowa crash as well. Devastating to the people directly affected, but no big deal otherwise.

Other people's lives are always no big deal, unless we make it our deal.

I'm not writing much here about the story of Universal Harvester. It's set somewhere around 2000, maybe a few years later or earlier, in a small video shop. Jeremy, a clerk in that store, gets reports that there are other scenes taped over some of the movies -- we're long enough ago, or far enough out, that VHS is the major format. He watches the scenes, which are clearly amateur: shaky camera, no dialogue, long shots of not much happening. They're also clearly from somewhere nearby. And they might be of something horrible happening: there are figures in masks, or tied to chairs, or huddled under tarps while a booted foot kicks them.

Other people's lives are always no big deal, unless we make it our deal.

Jeremy makes it his deal. He has a deep connection with the film-maker, which he won't know -- which the reader won't know -- until much later. Jeremy investigates. He watches the tapes. He shares them with others, who are also worried and appalled. They make plans and theories. They think they can find something wrong and fix it. But, again, this is not a horror novel.

It's not a novel about people chasing people with axes, at least. Not about supernatural forces from outside the world that are the real source of evil. Not about stopping the One Bad Thing, despite huge costs, to put the world right. It's not a horror novel. The real world, and the world of Universal Harvester, doesn't have horrors like those.

It has horrors like mothers that die, suddenly. Or that disappear, in a way that's worse than death. And it has people who have to go on living, on those oblivious Iowa two-lane roads, after those horrors happen. Just like you and me, in our own ways, in our own places.

It's a Mountain Goats song, on a larger scale -- a story of people trying to live their lives under adversity and neglect and fate. There are no easy answers, no horror-novel monster that can be killed to make the world better. The world only gets better day by day, through everyone's efforts, in tiny increments. And maybe it doesn't seem to get any better at all. And so there's no moment at the end when you know you've killed the monster. Because the monster is life. The monster is other people. The monster is you. The monster is everything and nothing.

Universal Harvester is a strong step forward from an already strong first novel in Wolf in White Van. Darnielle keeps his focus on people and their lives, with a deep sympathy and understanding of grief and loss and sadness. As long as you don't expect it to become a horror novel, you can get a lot out of it.

Tuesday, July 11, 2017

Sweaterweather and Other Short Stories by Sara Varon

This is not a new book by Sara Varon, cartoonist of Robot Dreams and Bake Sale. That may be slightly disappointing.

It is an old book by Varon -- originally published as her first collection back in 2003 -- expanded with as much new material as old, so it's kinda new, and probably unfamiliar to most of Varon's audience (who I suspect were, in most cases, not alive yet in 2003).

So this new edition of Sweaterweather and Other Short Stories has the eight stories from the 2003 first edition (plus the cover, presented as an interior spread), which originally appeared various places in 2002 and 2003. And it also has nine newer stories, created since the first edition of Sweaterweather and running up through 2014.

Some are fictional, and some are about Varon's own life, though the distinction gets muddy -- she draws all of her characters as animals and robots and creatures, and some of the "fictional" stories are directly from her life, just not presented as a "true" story about "Sara Varon." And it's all appropriate for fairly new readers -- say the middle reaches of elementary school, and maybe even a bit lower -- with an intrinsic sweetness and inquisitiveness that kids that age love and embody.

So the stories that aren't Varon showing us around parts of the world -- that aren't specifically nonfiction with a "Sara Varon" narrator -- are set in her usual Busytown-style kids-world, where all of the characters have adult lives and responsibilities (jobs, shopping, errands, and so on) but are essentially kids, almost playacting in that world. And, of course, everything is nice, and conflicts are almost entirely avoided. It's a sweet, lovely, nurturing world of happy creatures who like each other and maintain great friendships.

A steady diet of that would be too much for most of us, but it's a great thing to dip into now and then, to wash off all of the cynicism and unpleasantness of the adult world. Varon's world is a kinder, happier place than the one we really live in, and should be celebrated for that. I hope this book is in a million schoolrooms and libraries, and as many homes as it can find a place in.

It is an old book by Varon -- originally published as her first collection back in 2003 -- expanded with as much new material as old, so it's kinda new, and probably unfamiliar to most of Varon's audience (who I suspect were, in most cases, not alive yet in 2003).

So this new edition of Sweaterweather and Other Short Stories has the eight stories from the 2003 first edition (plus the cover, presented as an interior spread), which originally appeared various places in 2002 and 2003. And it also has nine newer stories, created since the first edition of Sweaterweather and running up through 2014.

Some are fictional, and some are about Varon's own life, though the distinction gets muddy -- she draws all of her characters as animals and robots and creatures, and some of the "fictional" stories are directly from her life, just not presented as a "true" story about "Sara Varon." And it's all appropriate for fairly new readers -- say the middle reaches of elementary school, and maybe even a bit lower -- with an intrinsic sweetness and inquisitiveness that kids that age love and embody.

So the stories that aren't Varon showing us around parts of the world -- that aren't specifically nonfiction with a "Sara Varon" narrator -- are set in her usual Busytown-style kids-world, where all of the characters have adult lives and responsibilities (jobs, shopping, errands, and so on) but are essentially kids, almost playacting in that world. And, of course, everything is nice, and conflicts are almost entirely avoided. It's a sweet, lovely, nurturing world of happy creatures who like each other and maintain great friendships.

A steady diet of that would be too much for most of us, but it's a great thing to dip into now and then, to wash off all of the cynicism and unpleasantness of the adult world. Varon's world is a kinder, happier place than the one we really live in, and should be celebrated for that. I hope this book is in a million schoolrooms and libraries, and as many homes as it can find a place in.

Monday, July 10, 2017

Reviewing the Mail: Week of 7/8

Another week is gone by, so I get to tell you about whatever books showed up serendipitously on my doorstep.

This week, it's one book: Adam Christopher's Killing Is My Business. It's the fourth in his series about a robot private detective in LA -- an alternate past LA, I think -- after Brisk Money, Made to Kill, and Standard Hollywood Depravity. I see that Christopher's robot here, Raymond Electromatic, has gone through a job transition since the series began: he's now working as a hitman rather than an investigator. (As the title notes.) I'm not sure how I've managed not to read this series before; it looks like exactly my kind of thing.

Anyway, this one is in front of me now, and it's a hardcover from Tor, officially hitting stores on July 25. With any luck, I'll read it soon.

This week, it's one book: Adam Christopher's Killing Is My Business. It's the fourth in his series about a robot private detective in LA -- an alternate past LA, I think -- after Brisk Money, Made to Kill, and Standard Hollywood Depravity. I see that Christopher's robot here, Raymond Electromatic, has gone through a job transition since the series began: he's now working as a hitman rather than an investigator. (As the title notes.) I'm not sure how I've managed not to read this series before; it looks like exactly my kind of thing.

Anyway, this one is in front of me now, and it's a hardcover from Tor, officially hitting stores on July 25. With any luck, I'll read it soon.

Sunday, July 09, 2017

Incoming Books: July 5 and 8