You know, I think Gabby Schulz may just be a tad bit dramatic.

It's a feeling I have -- partially based on my readings of his earlier books Monsters and Welcome to the Dahl House, partially because he can't seem to decide if he is "Ken Dahl" or "Gabby Schulz," and partly because Sick is possibly the most self-dramatizing book I've ever seen in my life.

Admittedly, it's the record of a time Schulz thought he might be dying, which does tend to concentrate the mind. (But, then again, says the contrarian part of my mind -- didn't he recover from this fever without any medical intervention? Isn't it possible that he's just really, really whiny when he's sick?)

And, of course, it's a book: the only record we have of Schulz's sickness is what he tells us himself, on large comics pages soaked in bile and misery, full of jaundice yellow and starless black. It could all be fiction. Just because it's by someone named Gabby Schulz and about someone named Gabby Schulz doesn't mean it's meant to be taken literally.

But I think it is. I think Schulz means every word, every pen-stroke of this book, and that's the way he works in comics: heart on the sleeve at all times, everything out there and exposed, all raw nerves and naked emotion and pure pleading about what he thinks are the most important things at every moment. It would be an exhausting way to live; it can be overwhelming even in a short graphic novel like this one -- particularly one so oversized and focused on the negative as Sick.

Gabby Schulz is negative. Everything I've seen of his work, under either name, is all about the things he loathes and can't stand -- himself always first and foremost among them. Schulz is the kind of left-winger who is both contorted into knots by his unearned privilege as a white American man and sent into a frenzy by the horrible treatment he continuously endures as an unskilled worker in that clearly hellish American society. His getting sick seems to mostly be of interest as a way to ramp up the self-loathing to ever greater heights -- to show how much he can really hate things when he gets going.

Sick is a book in which there is nothing good. There can be nothing good. To be Gabby Schulz is to be cursed: the most horrible human that ever lived, worthless and pitiful and also complicit in the worst society in the history of the world, a pyramid of horrors piled on top of each other without end.

Schulz realizes this, in a way: the book is in large part his own arguments to himself that life -- his life, specifically -- is worthless and horrible and better ended, and his feeble occasional moments of fighting against that sense.

It's not a book to read if you are in any way depressed, or suicidal, or unhappy about life. Only the sunniest of Pollyannas could read Sick without flinching, or worse.

All this is presented in vibrant, eye-catching, torn-from-his-heart art -- glorious in its hideousness and spleen. And his words are precise if not measured: always pushing further and always obsessively circling that same central conceit: that to be Gabby Schulz is a horrible, terrible, worthless thing, even more so when he has a fever.

I can't exactly recommend this book. It's so far over the top there's cloud cover obscuring its lower reaches. It is absurdly strident about its every last thought. But it is hugely impressive, and uniquely powerful, and utterly itself. It is Sick. Take that word in whatever sense you like.

A Weblog by One Humble Bookman on Topics of Interest to Discerning Readers, Including (Though Not Limited To) Science Fiction, Books, Random Thoughts, Fanciful Family Anecdotes, Publishing, Science Fiction, The Mating Habits of Extinct Waterfowl, The Secret Arts of Marketing, Other Books, Various Attempts at Humor, The Wonders of New Jersey, the Tedious Minutiae of a Boring Life, Science Fiction, No Accounting (For Taste), And Other Weighty Matters.

Friday, August 31, 2018

Thursday, August 30, 2018

Book-A-Day 2018 #242: Mrs. Fletcher by Tom Perrotta

Other people's secrets are always enticing. So much fiction is explicitly or implicitly about that idea: the desire to know what our neighbors are really doing behind closed doors.

Or, even more, what they're thinking. Pulp fiction cares about bodies; smart fiction cares about minds. What do other people think and feel -- what do they want and how do they struggle with the things they want?

Tom Perrotta has made a career of writing novels and stories about "normal" suburbanites and their secret lives, from Bad Haircut to The Abstinence Teacher. (I choose those points for two reasons: one, that's as far as I've read, since I haven't managed to get to his previous novel, The Leftovers. And, two, I only have a link for Abstinence because I read all of his other books before this blog.)

But Mrs. Fletcher feels even more so than his previous books: it's a novel about internet porn and college hookups, about sexual desire and trying to find the right partner, about how to navigate sex in the 21st century as a middle-aged woman or a college-age man. It's a fizzy, Zeitgeist-y novel -- or it was when Perrotta was finishing it up in 2016, before American society decided to be about entirely different, more contentious things for a few years. But sex is always there, and The Way We Do Sex Now is always a popular topic for books, from Sex and the Single Girl to Sex and the City.

Eve Fletcher is in early middle age: mid-forties, divorced, attractive and slim, with one son (only semi-loutish) heading off to college as the book opens. She has a serious job running the local Senior Center, in the fictionalized Massachusetts bedroom community she lives in -- like all of Perrotta's novels, it takes place in a suburbia much like the one he lives in personally, and is deeply informed by the lives and foibles of the upper-middle class in and around their tasteful homes.

The other major viewpoint character of Mrs. Fletcher is that semi-loutish son: Brendan. He's a jock and a party kid, smart enough not to have had to work hard for anything yet, attractive enough ditto, athletic enough double ditto. He's picked a school at least as much for the partying he expects to do there, and, has apparently never thought deeply about anything.

(There's a third semi-major viewpoint character, who I probably shouldn't spoil. But it's mostly the story of Eve and Brendan, in their different places, as they figure out what Sex Is -- or Should Be -- as they change their life circumstances.)

Eve is left alone: she takes a class at the local community college to get her out of the house and thinking about serious things. Unlike her son, she likes to think. Perrotta also explicitly positions her as someone who already got a Master's degree as an adult: she was used to juggling family and work and classwork while Brendan was younger and his father was flaking out of their lives, so her new life leaves her too little to do.

She falls into the Internet, like so many people who are alone or lonely: first Facebook, like everyone else. But she's still young, and it's been a long time since she's had a relationship -- Perrotta never puts it that crudely, but Eve is definitely horny. And so she finds porn online, settling in to spend many hours on a site Perrota calls MILFateria, which starts to affect how she sees herself and her relationships with other people.

That could be good: Eve has been a non-sexual person for so long, as Brendan's Mom and The Boss at the senior center, that reclaiming herself is positive. But she lives out in random suburbia, among married couples and her co-workers and a bunch of old people at the center -- who can she find, and how can she connect?

Meanwhile, Brendan is having his own issues fitting in. At first, his roommate and two other guys on their hall are his perfect buds: equally ripped, equally shallow, totally matched in wanting to hang out and drink and smoke and play video games and slack off and party with hot girls. But they start doing things without him, like having a serious (in more than one sense) girlfriend, or actually doing their classwork, or just seeing college as a place to become someone new and different. Brendan doesn't think about what he wants, but what he wants instinctively is for nothing to ever change: to keep drifting through life on weed and beer and lacrosse and blowjobs -- all the things that he assumes will just keep coming to him because he's just that awesome.

Eve and Brendan both make bad choices. You can argue about the word "bad," I suppose -- and maybe even the word "choices." They do things, each of them, that are not advisable. Things don't work out as they expect in their heads. Sex is more complicated and difficult than their dreams of sex, and other people don't follow the scripts porn or privilege write for them.

Mrs. Fletcher is the story of a semester, more or less. One woman yearns for something new and one man bumbles in trying to keep doing the same thing in a new place. Perrotta sees deeply into both of them, and into many of the people around them -- that doesn't mean they're admirable, or heroic, or wonderful, because they're not. They're all just people, and people screw up all the time. It's what makes them people.

This is a thoughtful, surprisingly encompassing novel about sex in the 21st century: age, gender roles, gender identification, orientation, feminism, power relationships, privilege, and, in the end, the central importance of mindfulness: of understanding both what you're doing and why you're doing it. As usual, Perrotta is great with flawed, interesting people and constructs loose plots that give room to explore all of his concerns and allow his characters enough rope to get to the end of their tethers.

Or, even more, what they're thinking. Pulp fiction cares about bodies; smart fiction cares about minds. What do other people think and feel -- what do they want and how do they struggle with the things they want?

Tom Perrotta has made a career of writing novels and stories about "normal" suburbanites and their secret lives, from Bad Haircut to The Abstinence Teacher. (I choose those points for two reasons: one, that's as far as I've read, since I haven't managed to get to his previous novel, The Leftovers. And, two, I only have a link for Abstinence because I read all of his other books before this blog.)

But Mrs. Fletcher feels even more so than his previous books: it's a novel about internet porn and college hookups, about sexual desire and trying to find the right partner, about how to navigate sex in the 21st century as a middle-aged woman or a college-age man. It's a fizzy, Zeitgeist-y novel -- or it was when Perrotta was finishing it up in 2016, before American society decided to be about entirely different, more contentious things for a few years. But sex is always there, and The Way We Do Sex Now is always a popular topic for books, from Sex and the Single Girl to Sex and the City.

Eve Fletcher is in early middle age: mid-forties, divorced, attractive and slim, with one son (only semi-loutish) heading off to college as the book opens. She has a serious job running the local Senior Center, in the fictionalized Massachusetts bedroom community she lives in -- like all of Perrotta's novels, it takes place in a suburbia much like the one he lives in personally, and is deeply informed by the lives and foibles of the upper-middle class in and around their tasteful homes.

The other major viewpoint character of Mrs. Fletcher is that semi-loutish son: Brendan. He's a jock and a party kid, smart enough not to have had to work hard for anything yet, attractive enough ditto, athletic enough double ditto. He's picked a school at least as much for the partying he expects to do there, and, has apparently never thought deeply about anything.

(There's a third semi-major viewpoint character, who I probably shouldn't spoil. But it's mostly the story of Eve and Brendan, in their different places, as they figure out what Sex Is -- or Should Be -- as they change their life circumstances.)

Eve is left alone: she takes a class at the local community college to get her out of the house and thinking about serious things. Unlike her son, she likes to think. Perrotta also explicitly positions her as someone who already got a Master's degree as an adult: she was used to juggling family and work and classwork while Brendan was younger and his father was flaking out of their lives, so her new life leaves her too little to do.

She falls into the Internet, like so many people who are alone or lonely: first Facebook, like everyone else. But she's still young, and it's been a long time since she's had a relationship -- Perrotta never puts it that crudely, but Eve is definitely horny. And so she finds porn online, settling in to spend many hours on a site Perrota calls MILFateria, which starts to affect how she sees herself and her relationships with other people.

That could be good: Eve has been a non-sexual person for so long, as Brendan's Mom and The Boss at the senior center, that reclaiming herself is positive. But she lives out in random suburbia, among married couples and her co-workers and a bunch of old people at the center -- who can she find, and how can she connect?

Meanwhile, Brendan is having his own issues fitting in. At first, his roommate and two other guys on their hall are his perfect buds: equally ripped, equally shallow, totally matched in wanting to hang out and drink and smoke and play video games and slack off and party with hot girls. But they start doing things without him, like having a serious (in more than one sense) girlfriend, or actually doing their classwork, or just seeing college as a place to become someone new and different. Brendan doesn't think about what he wants, but what he wants instinctively is for nothing to ever change: to keep drifting through life on weed and beer and lacrosse and blowjobs -- all the things that he assumes will just keep coming to him because he's just that awesome.

Eve and Brendan both make bad choices. You can argue about the word "bad," I suppose -- and maybe even the word "choices." They do things, each of them, that are not advisable. Things don't work out as they expect in their heads. Sex is more complicated and difficult than their dreams of sex, and other people don't follow the scripts porn or privilege write for them.

Mrs. Fletcher is the story of a semester, more or less. One woman yearns for something new and one man bumbles in trying to keep doing the same thing in a new place. Perrotta sees deeply into both of them, and into many of the people around them -- that doesn't mean they're admirable, or heroic, or wonderful, because they're not. They're all just people, and people screw up all the time. It's what makes them people.

This is a thoughtful, surprisingly encompassing novel about sex in the 21st century: age, gender roles, gender identification, orientation, feminism, power relationships, privilege, and, in the end, the central importance of mindfulness: of understanding both what you're doing and why you're doing it. As usual, Perrotta is great with flawed, interesting people and constructs loose plots that give room to explore all of his concerns and allow his characters enough rope to get to the end of their tethers.

Wednesday, August 29, 2018

Book-A-Day 2018 #241: The Tooth by Cullen Bunn, Shawn Lee, and Matt Kindt

Reading comics digitally is weird for me: it's so disconnected from the physicality of a real book, and (at least the stuff I have, mostly publicity copies) generally lack covers and explanatory copy, so it dives right into story without any explanation as to how or why or who.

I also tend to have stuff that's been sitting around for a while, since I was getting digital review copies for most of the last decade but not actually reading more than a couple of them. (I very easily forget that I have a particular collection of electrons sitting in a folder somewhere; real physical objects on a shelf are much better at reminding me they exist and are waiting to be read.)

For example, I just this second tracked down a cover for this book, so I could slap it into the top left of this post. It looks completely unfamiliar, and The Tooth is a book that was published in 2011 and which I presumably have had since then (or maybe slightly earlier, given publishing schedules).

I also don't have much of a clue how The Tooth was positioned -- it's clearly a pseudo-retro superhero comic, the mid-70s rebirth of a Silver Age hero, but how serious we were meant to take it isn't as clear -- or who the audience was. And it seems to have disappeared without a trace since then, so whoever the audience was supposed to be, I don't think they embraced it as fully as the creators [1] expected.

What this book supposedly "reprints" -- I don't think it was published separately beforehand, but I never bet against serialization when talking about comics of giant things punching each other -- is issues 34 to 39 of The Tooth, the fourth series featuring that character (after Journey Into Terror, Savage Tooth, and The House of Unknown Terror), just a few issues before the title apparently ended. (As we find from some kid's "The Tooth Want List," interpolated between two of the "issues.")

It is, of course, the All-New All Different Tooth, with a new supporting cast and what's probably supposed to be a slightly different take on his origin and purpose. So some schmo inherits a haunted house from a creepy uncle, and learns that he's also inherited...um, well, that one of his teeth grows to a massive size, leaps out of his mouth, and fights evil.

As one does.

The schmo finds a knowledgeable fellow -- who is the one hold-over from the prior cast -- to give him the silly comic-book background, which is pseudo-mythological in the Thor vein. The Tooth and his compatriots are the warriors grown from the teeth of the dragon Cadmus slew in Greek mythology (the ones who founded Thebes, though that part doesn't come up here).

There is, of course, also a villain, who wants to resurrect the dragon whose teeth those warriors originally were, and whose plot very nearly comes true. But, obviously, righteousness wins out in the end.

All this is told on what's supposed to be yellowing newsprint pages -- including letter columns -- tattered covers, and some interpolated material. (There's also what looks like some kid's increasingly-good drawings of The Tooth in the front matter -- I think he's supposed to be the kid who owned these comics.)

So it's all Superhero Comics, subcategory Deliberately Retro, tertiary category Goofy. It's all presented straight on the page, like a real artifact from nearly fifty years ago, but it's impossible to forget that it's a story about a tooth that enlarges to fight evil through mega-violence.

I think I was originally interested in The Tooth because of the Matt Kindt connection; he's made a lot of good comics out of various odd genre materials. But he's just drawing here. This is a very faithful recreation of a kind of comic that was deeply silly to begin with: I appreciate the love and craft that went into it, but I have to wonder why anyone thought this would be a good idea. It's the comics equivalent of a novel-length shaggy dog joke.

[1] Cullen Bunn and Shawn Lee co-write, Matt Kindt does all of the art and colors and apparently book design.

I also tend to have stuff that's been sitting around for a while, since I was getting digital review copies for most of the last decade but not actually reading more than a couple of them. (I very easily forget that I have a particular collection of electrons sitting in a folder somewhere; real physical objects on a shelf are much better at reminding me they exist and are waiting to be read.)

For example, I just this second tracked down a cover for this book, so I could slap it into the top left of this post. It looks completely unfamiliar, and The Tooth is a book that was published in 2011 and which I presumably have had since then (or maybe slightly earlier, given publishing schedules).

I also don't have much of a clue how The Tooth was positioned -- it's clearly a pseudo-retro superhero comic, the mid-70s rebirth of a Silver Age hero, but how serious we were meant to take it isn't as clear -- or who the audience was. And it seems to have disappeared without a trace since then, so whoever the audience was supposed to be, I don't think they embraced it as fully as the creators [1] expected.

What this book supposedly "reprints" -- I don't think it was published separately beforehand, but I never bet against serialization when talking about comics of giant things punching each other -- is issues 34 to 39 of The Tooth, the fourth series featuring that character (after Journey Into Terror, Savage Tooth, and The House of Unknown Terror), just a few issues before the title apparently ended. (As we find from some kid's "The Tooth Want List," interpolated between two of the "issues.")

It is, of course, the All-New All Different Tooth, with a new supporting cast and what's probably supposed to be a slightly different take on his origin and purpose. So some schmo inherits a haunted house from a creepy uncle, and learns that he's also inherited...um, well, that one of his teeth grows to a massive size, leaps out of his mouth, and fights evil.

As one does.

The schmo finds a knowledgeable fellow -- who is the one hold-over from the prior cast -- to give him the silly comic-book background, which is pseudo-mythological in the Thor vein. The Tooth and his compatriots are the warriors grown from the teeth of the dragon Cadmus slew in Greek mythology (the ones who founded Thebes, though that part doesn't come up here).

There is, of course, also a villain, who wants to resurrect the dragon whose teeth those warriors originally were, and whose plot very nearly comes true. But, obviously, righteousness wins out in the end.

All this is told on what's supposed to be yellowing newsprint pages -- including letter columns -- tattered covers, and some interpolated material. (There's also what looks like some kid's increasingly-good drawings of The Tooth in the front matter -- I think he's supposed to be the kid who owned these comics.)

So it's all Superhero Comics, subcategory Deliberately Retro, tertiary category Goofy. It's all presented straight on the page, like a real artifact from nearly fifty years ago, but it's impossible to forget that it's a story about a tooth that enlarges to fight evil through mega-violence.

I think I was originally interested in The Tooth because of the Matt Kindt connection; he's made a lot of good comics out of various odd genre materials. But he's just drawing here. This is a very faithful recreation of a kind of comic that was deeply silly to begin with: I appreciate the love and craft that went into it, but I have to wonder why anyone thought this would be a good idea. It's the comics equivalent of a novel-length shaggy dog joke.

[1] Cullen Bunn and Shawn Lee co-write, Matt Kindt does all of the art and colors and apparently book design.

Tuesday, August 28, 2018

Book-A-Day 2018 #240: Labor Days 2: Just Another Damn Day by Phillip Gelatt and Rick Lacy

Once again, I've gotten to a book several years too late, and that's confusing me. I read the first Labor Days book (written by Phillip Gelatt and drawn by Rick Lacy, neither of whom I know from anything else) back in 2009 and reviewed it for ComicMix then. And then I got a spiffy digital copy of the sequel later that same year...

...and it sat quietly on my device for nearly a decade.

Lesson: I am not dependable in reading anything, but I'm particularly prone to forgetting things that I have in purely-electrons form. If it's not on a shelf where I can see it, I'm afraid it drops out of mind very swiftly.

Anyway, I had a week where I was specifically reading digital things on that device, because I was traveling, and so I finally realized I had Labor Days 2: Just Another Damn Day and actually read it.

And it's been long enough that I don't trust my memories of the first book. I don't think it read like a weird mash-up of a Mark Millar story and a parody of a Mark Millar story, but this one definitely does. (At least to me, this many years later.) The main character is still an Everyman, subcategory Dull Ordinary Bloke, and there's still a big conspiracy that runs the world or something, but this time it all seems to be more specific and moving forward. (My memory of the first book was that it threw that hero, one Benton "Bags" Bagswell right into the deep end and just had complications run around him for about two hundred pages until the book hit something like an ending.)

So there's a guy called "the Face of History" -- literal, actual guy, also the personification of history -- and Bags is having prophetic dreams in which he's told to find and kill that guy to take his place, driven by some female supernatural entity that I don't think is ever named here but whose job seems to be lining up losers to kill the Face of History about every sixty years or so.

The Face has massive secret societies devoted to him around the world -- well, secretly devoted to him, since most of the devotees don't actually know that. And there are what seems to be an equally large group of equally crazy, equally secret societies headed by people who know the Face exists and want to depose and/or kill and/or replace and/or subvert him.

So Bags and his hot redheaded bespectacled super-competent girlfriend Victoria have been wandering around, trying to join looney groups in hopes that will get them close to The Face. It hasn't been working particularly well, but Bags has gotten to drink a lot of beer, so it's not all lost. But the sequence of events that starts at the beginning of this book sends them through some new organizations, and finally to The Face. Also, Bags's secret dream-fairy finally realizes how stupid he is and tells him explicitly what she wants him to do.

Again, this all seems like either a rejected Mark Millar story, circa 2007, or someone's idea of a parody of a Mark Millar story, only it would need to be, y'know, actually parodic at some point. Instead, it's adventurous in a manner that's serious about half the time and absolutely unable to be taken seriously the rest of the time.

Look, this clearly isn't a deathless classic of comics: I knew that going in. But I didn't expect to be this confused at the end....

...and it sat quietly on my device for nearly a decade.

Lesson: I am not dependable in reading anything, but I'm particularly prone to forgetting things that I have in purely-electrons form. If it's not on a shelf where I can see it, I'm afraid it drops out of mind very swiftly.

Anyway, I had a week where I was specifically reading digital things on that device, because I was traveling, and so I finally realized I had Labor Days 2: Just Another Damn Day and actually read it.

And it's been long enough that I don't trust my memories of the first book. I don't think it read like a weird mash-up of a Mark Millar story and a parody of a Mark Millar story, but this one definitely does. (At least to me, this many years later.) The main character is still an Everyman, subcategory Dull Ordinary Bloke, and there's still a big conspiracy that runs the world or something, but this time it all seems to be more specific and moving forward. (My memory of the first book was that it threw that hero, one Benton "Bags" Bagswell right into the deep end and just had complications run around him for about two hundred pages until the book hit something like an ending.)

So there's a guy called "the Face of History" -- literal, actual guy, also the personification of history -- and Bags is having prophetic dreams in which he's told to find and kill that guy to take his place, driven by some female supernatural entity that I don't think is ever named here but whose job seems to be lining up losers to kill the Face of History about every sixty years or so.

The Face has massive secret societies devoted to him around the world -- well, secretly devoted to him, since most of the devotees don't actually know that. And there are what seems to be an equally large group of equally crazy, equally secret societies headed by people who know the Face exists and want to depose and/or kill and/or replace and/or subvert him.

So Bags and his hot redheaded bespectacled super-competent girlfriend Victoria have been wandering around, trying to join looney groups in hopes that will get them close to The Face. It hasn't been working particularly well, but Bags has gotten to drink a lot of beer, so it's not all lost. But the sequence of events that starts at the beginning of this book sends them through some new organizations, and finally to The Face. Also, Bags's secret dream-fairy finally realizes how stupid he is and tells him explicitly what she wants him to do.

Again, this all seems like either a rejected Mark Millar story, circa 2007, or someone's idea of a parody of a Mark Millar story, only it would need to be, y'know, actually parodic at some point. Instead, it's adventurous in a manner that's serious about half the time and absolutely unable to be taken seriously the rest of the time.

Look, this clearly isn't a deathless classic of comics: I knew that going in. But I didn't expect to be this confused at the end....

Monday, August 27, 2018

Book-A-Day 2018 #239: Esperanza by Jaime Hernandez

Everyone gets older, in any world that tries to be real. Most comic-book worlds don't try -- how old is Peter Parker now? And how old was he in 1966?

Jaime Hernandez's comics world is real -- or as real as it wants to be, with only minor occasional eruptions of superheroes and prosolar mechanics. And that world tends to move in forward in time in fits and starts: there will be a clump of stories with his characters at one point in their life, coming out over two or five or six years but covering maybe a month or two of their lives, and then the next clump will begin after that, with another few years passed almost without noticing.

That's how we live in our own lives -- at least how I do. Everything seems to be basically the same for a while, with years that are all pretty much the same rhythms, and then you look up and everything is suddenly different.

Esperanza collects comics from the second Love and Rockets series, from roughly 2000 through 2007. I could say that this book sees the focus snap back to Maggie and Hopey -- which is semi-true, since there's a long story sequence for each of them here -- after the stories in Penny Century, which spread further out into the cast. But Ray D. is just as prominent here as he was in Penny Century: there, he was mooning over Penny; here's he's in a complicated relationship with "the Frogmouth," a stripped named Vivian who also seems to have an unrealized crush on Maggie. Penny herself doesn't show up as often this time out, true: she drops in and out of the Locas world regularly over the years, as if only visiting it from her own, more glamorous and exciting universe.

And there's two major new characters here, both younger than the aging Locas: Vivian "the Frogmouth" and Angel Rivera, whose name we're not actually told directly at any point. So Maggie is still the center of this world -- Vivian has something like a crush on her; Ray D. is still semi-obsessed with her; Angel lives in the apartment complex she manages; and we all know about Hopey -- but it's a large world, full of people with cross-connections.

Esperanza starts off with the ten-part story "Maggie," only briefly interrupted by a Ray D. appearance. That's more reductive than the book really is, though: all of the stories in Esperanza are telling the same overall story. Some are Maggie stories, some are Hopey stories, some are Ray D. stories, and some even more exotic, but these are all people in the same circle and the stories are all placed in time. It's all one piece in the end: it all comes together.

Maggie is still managing that broken-down apartment complex in LA, blonde and chubby in what's probably her early forties. She's still sabotaging herself, still helping Izzy manage with her minor-author fame, still circling Hopey, who is tending bar nearby and working in some kind of office. (If there was ever any explanation of what Hopey did for close to ten years in that office with Guy Goforth, I missed it.)

Vivian -- a bombshell of a woman of twenty-five or so who generates trouble just by being in the vicinity -- is the motivating force for most of what happens in Esperanza. She dates Ray D.; she almost has an affair with Maggie; she's caught up in various low-life gangsters and ex-boyfriends who don't realize they're ex. And she can spark a fight just by standing there.

The rest of the plot is set in motion by Hopey's old enemy Julie Wree, whose mean-girl circle is still intact, still more successful than our heroines, and running a popular public-access TV show, where Izzy appears once and Vivian is the "ring girl," coming through boxing-style in a bathing suit holding large cards.

Well, there's a lot of incidents here that aren't set in motion by anything in particular. Hernandez's characters are restless and unsatisfied and rarely happy with themselves -- and that drives them to do a lot of what they do, in this book and in all of his other work.

The back half of Esperanza semi-alternates stories about Vivian and Ray D.'s messy relationship with the "Day By Day With Hopey" series. Hopey is studying to be a teacher's assistant -- we don't see her do much studying, but we see her leave the old office job and start the new job -- and it looks like she's finally growing up, finally leaving behind the reflexive shit-stirring that was so central to her early punk personality. (You can see Vivian as the same kind of person, only more so: Hopey fomented chaos deliberately, Vivian is an endless source of chaos in herself.) But she's also having a slow break-up with her live-in girlfriend Rosie while flirting with saying "I love you" to Maggie, chasing the cute girl fitting her for glasses and having a friends-with-benefits thing going on with yet another woman, Grace.

This is a world: these people all know each other. Some of them like each other, some of them love each other, some of them want to fuck each other, some of them want to kill each other. Actually, "some" in the previous sentence might be understating it: the thing about Hernandez's cast is that they all feel like that to all of the rest of them, more or less, at different times. (Except Julie Wree: everyone hates that bitch.) Epseranza has stories from the time when some of them are starting to think that they might be getting a little to old to be this crazy all the time.

Maybe they're right. But I also notice that Hernandez has been bringing in newer, younger women all of the time -- Gina and Danita previously, Vivian and Angel most prominently here -- so that, if his old cast ever does grow up too much, he has more Locas to keep it all going.

I wouldn't worry about that: nobody ever really grows up. We just get old, faster than we expected. And we're all still crazy: that's why we read Jaime Hernandez, to show us the ways we are, so we can laugh and recognize our own craziness.

Jaime Hernandez's comics world is real -- or as real as it wants to be, with only minor occasional eruptions of superheroes and prosolar mechanics. And that world tends to move in forward in time in fits and starts: there will be a clump of stories with his characters at one point in their life, coming out over two or five or six years but covering maybe a month or two of their lives, and then the next clump will begin after that, with another few years passed almost without noticing.

That's how we live in our own lives -- at least how I do. Everything seems to be basically the same for a while, with years that are all pretty much the same rhythms, and then you look up and everything is suddenly different.

Esperanza collects comics from the second Love and Rockets series, from roughly 2000 through 2007. I could say that this book sees the focus snap back to Maggie and Hopey -- which is semi-true, since there's a long story sequence for each of them here -- after the stories in Penny Century, which spread further out into the cast. But Ray D. is just as prominent here as he was in Penny Century: there, he was mooning over Penny; here's he's in a complicated relationship with "the Frogmouth," a stripped named Vivian who also seems to have an unrealized crush on Maggie. Penny herself doesn't show up as often this time out, true: she drops in and out of the Locas world regularly over the years, as if only visiting it from her own, more glamorous and exciting universe.

And there's two major new characters here, both younger than the aging Locas: Vivian "the Frogmouth" and Angel Rivera, whose name we're not actually told directly at any point. So Maggie is still the center of this world -- Vivian has something like a crush on her; Ray D. is still semi-obsessed with her; Angel lives in the apartment complex she manages; and we all know about Hopey -- but it's a large world, full of people with cross-connections.

Esperanza starts off with the ten-part story "Maggie," only briefly interrupted by a Ray D. appearance. That's more reductive than the book really is, though: all of the stories in Esperanza are telling the same overall story. Some are Maggie stories, some are Hopey stories, some are Ray D. stories, and some even more exotic, but these are all people in the same circle and the stories are all placed in time. It's all one piece in the end: it all comes together.

Maggie is still managing that broken-down apartment complex in LA, blonde and chubby in what's probably her early forties. She's still sabotaging herself, still helping Izzy manage with her minor-author fame, still circling Hopey, who is tending bar nearby and working in some kind of office. (If there was ever any explanation of what Hopey did for close to ten years in that office with Guy Goforth, I missed it.)

Vivian -- a bombshell of a woman of twenty-five or so who generates trouble just by being in the vicinity -- is the motivating force for most of what happens in Esperanza. She dates Ray D.; she almost has an affair with Maggie; she's caught up in various low-life gangsters and ex-boyfriends who don't realize they're ex. And she can spark a fight just by standing there.

The rest of the plot is set in motion by Hopey's old enemy Julie Wree, whose mean-girl circle is still intact, still more successful than our heroines, and running a popular public-access TV show, where Izzy appears once and Vivian is the "ring girl," coming through boxing-style in a bathing suit holding large cards.

Well, there's a lot of incidents here that aren't set in motion by anything in particular. Hernandez's characters are restless and unsatisfied and rarely happy with themselves -- and that drives them to do a lot of what they do, in this book and in all of his other work.

The back half of Esperanza semi-alternates stories about Vivian and Ray D.'s messy relationship with the "Day By Day With Hopey" series. Hopey is studying to be a teacher's assistant -- we don't see her do much studying, but we see her leave the old office job and start the new job -- and it looks like she's finally growing up, finally leaving behind the reflexive shit-stirring that was so central to her early punk personality. (You can see Vivian as the same kind of person, only more so: Hopey fomented chaos deliberately, Vivian is an endless source of chaos in herself.) But she's also having a slow break-up with her live-in girlfriend Rosie while flirting with saying "I love you" to Maggie, chasing the cute girl fitting her for glasses and having a friends-with-benefits thing going on with yet another woman, Grace.

This is a world: these people all know each other. Some of them like each other, some of them love each other, some of them want to fuck each other, some of them want to kill each other. Actually, "some" in the previous sentence might be understating it: the thing about Hernandez's cast is that they all feel like that to all of the rest of them, more or less, at different times. (Except Julie Wree: everyone hates that bitch.) Epseranza has stories from the time when some of them are starting to think that they might be getting a little to old to be this crazy all the time.

Maybe they're right. But I also notice that Hernandez has been bringing in newer, younger women all of the time -- Gina and Danita previously, Vivian and Angel most prominently here -- so that, if his old cast ever does grow up too much, he has more Locas to keep it all going.

I wouldn't worry about that: nobody ever really grows up. We just get old, faster than we expected. And we're all still crazy: that's why we read Jaime Hernandez, to show us the ways we are, so we can laugh and recognize our own craziness.

Reviewing the Mail: Week of 8/25/18

Every week, I list new books here every Monday morning. Sometimes they're really new books -- just published, and sent to me as part of traditional publicity efforts. But, more often these days, they're things I've gotten in other ways for other reasons. They're still all new to me, and they could be new to you, as NBC used to say.

This week, I have four books I got from the local library:

Spoiled Brats is a 2014 collection of short stories by Simon Rich, author of the humor collections Free-Range Chickens and Ant Farm, the thematically too-tight collection The Last Girlfriend on Earth, and the humorous novel What in God's Name. (Links are to my posts about those books; Rich has also written another book or two I haven't gotten to yet.) I've found Rich to be killer at the traditional "Shouts & Murmurs"-length essay, but a bit thinner and more facile at longer pieces. But he's been consistently funny, so I'll give him another try.

(If you google him, he is also ridiculously boyish looking, which I'm sure is not his favorite thing in the world.)

My Boyfriend Is a Bear is a graphic novel by Pamela Ribon and Cat Farris about modern romance: Nora dated a bunch of unsuitable guys, and was ready to give up when she met someone adorable. As the title implies, he was an American Black Bear. I've seen good reviews of this book, which I hope slides into that sweet spot between allegory and silly.

My Boyfriend Is a Bear is a graphic novel by Pamela Ribon and Cat Farris about modern romance: Nora dated a bunch of unsuitable guys, and was ready to give up when she met someone adorable. As the title implies, he was an American Black Bear. I've seen good reviews of this book, which I hope slides into that sweet spot between allegory and silly.

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur, Vol. 1: BFF is, obviously, the first collection of another one of that clump of things called "good superhero comics." I'm not sure if it's "good" mostly because it's not about the same few boring old white guys, or if it has other qualities that also provide "good" -- but, what the hey, I'm reading giant piles of books this year so I'll give it a try. It's written by Brandon Montclare and Amy Reeder, with art by Natacha Bustos.

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur, Vol. 1: BFF is, obviously, the first collection of another one of that clump of things called "good superhero comics." I'm not sure if it's "good" mostly because it's not about the same few boring old white guys, or if it has other qualities that also provide "good" -- but, what the hey, I'm reading giant piles of books this year so I'll give it a try. It's written by Brandon Montclare and Amy Reeder, with art by Natacha Bustos.

And speaking of things people keep saying are "good superhero comics," I also have Captain Marvel, Vol. 1: Earth's Mightiest Hero, written by Kelly Sue DeConnick (with Christopher Sebela for a few issues) and drawn by a rotating crew: Dexter Soy, Emma Rios, and Filipe Andrade. Again, I'm not 100% clear if this is praised mostly because it's a woman punching bad guys all the time, but I'll find out.

And speaking of things people keep saying are "good superhero comics," I also have Captain Marvel, Vol. 1: Earth's Mightiest Hero, written by Kelly Sue DeConnick (with Christopher Sebela for a few issues) and drawn by a rotating crew: Dexter Soy, Emma Rios, and Filipe Andrade. Again, I'm not 100% clear if this is praised mostly because it's a woman punching bad guys all the time, but I'll find out.

Looking this up for a link, I see there was another Volume One for Cap from a 2014-2015 series; this is from the 2016 series. I have no idea if this Volume One is a good place to start, or if I should have found the other Volume One.

....and this is why I hate Marvel Comics. There is no way they're going to sell books to anyone not already reading Previews every month as long as they keep up that shit.

This week, I have four books I got from the local library:

Spoiled Brats is a 2014 collection of short stories by Simon Rich, author of the humor collections Free-Range Chickens and Ant Farm, the thematically too-tight collection The Last Girlfriend on Earth, and the humorous novel What in God's Name. (Links are to my posts about those books; Rich has also written another book or two I haven't gotten to yet.) I've found Rich to be killer at the traditional "Shouts & Murmurs"-length essay, but a bit thinner and more facile at longer pieces. But he's been consistently funny, so I'll give him another try.

(If you google him, he is also ridiculously boyish looking, which I'm sure is not his favorite thing in the world.)

My Boyfriend Is a Bear is a graphic novel by Pamela Ribon and Cat Farris about modern romance: Nora dated a bunch of unsuitable guys, and was ready to give up when she met someone adorable. As the title implies, he was an American Black Bear. I've seen good reviews of this book, which I hope slides into that sweet spot between allegory and silly.

My Boyfriend Is a Bear is a graphic novel by Pamela Ribon and Cat Farris about modern romance: Nora dated a bunch of unsuitable guys, and was ready to give up when she met someone adorable. As the title implies, he was an American Black Bear. I've seen good reviews of this book, which I hope slides into that sweet spot between allegory and silly. Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur, Vol. 1: BFF is, obviously, the first collection of another one of that clump of things called "good superhero comics." I'm not sure if it's "good" mostly because it's not about the same few boring old white guys, or if it has other qualities that also provide "good" -- but, what the hey, I'm reading giant piles of books this year so I'll give it a try. It's written by Brandon Montclare and Amy Reeder, with art by Natacha Bustos.

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur, Vol. 1: BFF is, obviously, the first collection of another one of that clump of things called "good superhero comics." I'm not sure if it's "good" mostly because it's not about the same few boring old white guys, or if it has other qualities that also provide "good" -- but, what the hey, I'm reading giant piles of books this year so I'll give it a try. It's written by Brandon Montclare and Amy Reeder, with art by Natacha Bustos. And speaking of things people keep saying are "good superhero comics," I also have Captain Marvel, Vol. 1: Earth's Mightiest Hero, written by Kelly Sue DeConnick (with Christopher Sebela for a few issues) and drawn by a rotating crew: Dexter Soy, Emma Rios, and Filipe Andrade. Again, I'm not 100% clear if this is praised mostly because it's a woman punching bad guys all the time, but I'll find out.

And speaking of things people keep saying are "good superhero comics," I also have Captain Marvel, Vol. 1: Earth's Mightiest Hero, written by Kelly Sue DeConnick (with Christopher Sebela for a few issues) and drawn by a rotating crew: Dexter Soy, Emma Rios, and Filipe Andrade. Again, I'm not 100% clear if this is praised mostly because it's a woman punching bad guys all the time, but I'll find out.Looking this up for a link, I see there was another Volume One for Cap from a 2014-2015 series; this is from the 2016 series. I have no idea if this Volume One is a good place to start, or if I should have found the other Volume One.

....and this is why I hate Marvel Comics. There is no way they're going to sell books to anyone not already reading Previews every month as long as they keep up that shit.

Sunday, August 26, 2018

Book-A-Day 2018 #238: Girlfiend by The Pander Brothers

I have never been so tempted to take Jacob and Arnold Pander's surname so literally.

Perhaps it's because Girlfiend started off as a screenplay, but this thin (but stylish) story of a runaway vampire girl and the boy she meets in the big city (Seattle) feels like a collection of second-hand attitudes and moments in search of a coherent plot or reason for being.

Don't get me wrong: it looks great, as always with the Panders, full of speed lines and slashing shadows and evocative eyes. They get into some complex page layouts, too, with negative effects overlaid on shard-like panels on big double-page spreads, to give comics the eyeball kicks of a big-screen movie. And this would be a lot of fun as a movie, though it feels like something you'd see in the second-run theater in about 1988. (The Panders have always felt like a window into a superstylish '80s; that's what they do.)

So a young woman gets off a bus in downtown Seattle, sometime that could be now but doesn't really feel like it. She's distracted and maybe a bit overwhelmed -- and she's killed, messily, in a car crash.

Cut to the local morgue, where tech Nick is working on her body. And she comes back to life after he removes a nasty piece of rebar from the middle of her chest. Her name is Karina, and, inevitably, she moves in with him within another scene or two.

She tries to hide her secrets, but it all comes out quickly: she's a vampire, one of the special "next-generation" kind who can go out by day, but otherwise has the usual vamp details -- fangs, needs to drink blood, young and beautiful forever, strong and agile and powerful.

Meanwhile, in the B plots, there's both a crew of criminals who have heisted something very valuable and dangerous (and keep getting themselves killed in various ways trying to open a safe and maneuver for control of it), and two detectives who spend a lot of time talking about justice and showing up after those criminals and others die in bloody ways.

Nick gets Karina to go after criminals for the blood she needs to drink -- which means, mostly, the gang I just mentioned. The two cops are more familiar with vampires than you'd expect. And a team from Karina's "family" is heading to town to return or eliminate her: no one is allowed to escape.

They all collide in the end, as they must. Since this is a comic, we don't get a Kenny Loggins song under the big fight, but we can imagine it. There's a happy ending for the heroes, since that's how '80s movies have to end. And, again, it all looks great, even if the story is nothing but B-movie cliches as far as the eye can see.

But if you're looking for the great lost Seattle vampire movie of the late '80s, you just might have found it in this comic.

Perhaps it's because Girlfiend started off as a screenplay, but this thin (but stylish) story of a runaway vampire girl and the boy she meets in the big city (Seattle) feels like a collection of second-hand attitudes and moments in search of a coherent plot or reason for being.

Don't get me wrong: it looks great, as always with the Panders, full of speed lines and slashing shadows and evocative eyes. They get into some complex page layouts, too, with negative effects overlaid on shard-like panels on big double-page spreads, to give comics the eyeball kicks of a big-screen movie. And this would be a lot of fun as a movie, though it feels like something you'd see in the second-run theater in about 1988. (The Panders have always felt like a window into a superstylish '80s; that's what they do.)

So a young woman gets off a bus in downtown Seattle, sometime that could be now but doesn't really feel like it. She's distracted and maybe a bit overwhelmed -- and she's killed, messily, in a car crash.

Cut to the local morgue, where tech Nick is working on her body. And she comes back to life after he removes a nasty piece of rebar from the middle of her chest. Her name is Karina, and, inevitably, she moves in with him within another scene or two.

She tries to hide her secrets, but it all comes out quickly: she's a vampire, one of the special "next-generation" kind who can go out by day, but otherwise has the usual vamp details -- fangs, needs to drink blood, young and beautiful forever, strong and agile and powerful.

Meanwhile, in the B plots, there's both a crew of criminals who have heisted something very valuable and dangerous (and keep getting themselves killed in various ways trying to open a safe and maneuver for control of it), and two detectives who spend a lot of time talking about justice and showing up after those criminals and others die in bloody ways.

Nick gets Karina to go after criminals for the blood she needs to drink -- which means, mostly, the gang I just mentioned. The two cops are more familiar with vampires than you'd expect. And a team from Karina's "family" is heading to town to return or eliminate her: no one is allowed to escape.

They all collide in the end, as they must. Since this is a comic, we don't get a Kenny Loggins song under the big fight, but we can imagine it. There's a happy ending for the heroes, since that's how '80s movies have to end. And, again, it all looks great, even if the story is nothing but B-movie cliches as far as the eye can see.

But if you're looking for the great lost Seattle vampire movie of the late '80s, you just might have found it in this comic.

Saturday, August 25, 2018

Book-A-Day 2018 #237: Ares & Aphrodite: Love Wars by Jamie S. Rich and Megan Levens

It can be hard to praise things for being small without sounding condescending.

Oh, what a quaint house!

Aren't you a darling little man!

What an adorable book!

I'm going to try to avoid that pitfall today. But what I like best about this graphic novel by writer Jamie S. Rich and artist Megan Levens is that it's not trying to do too much. Ares & Aphrodite tells the story of one couple -- well, one potential couple -- and how they got together, if, eventually, they do get together enough for that to be a story.

In a world of comics that seem to want to be widescreen media-spanning epics, Ares & Aphrodite aspires to be a really good small movie, the kind made for a TV channel that churlish men avoid or that plays in that one theater two towns over. It's about two people, their professional connection, and a low-stakes bet they make with each other.

Will Ares is the top divorce lawyer in town. Gigi Averelle runs Aphrodite's, the most exclusive wedding-planning service in town. "Town," in this case, is Los Angeles, which would normally mean both of these two are massively important, with egos to match -- but they're both awfully normal and down-to-earth. Both seem to be somewhere in their thirties: old enough to have succeeded, old enough to want something better, young enough to still have time ahead of them.

Evans Beatty is Ares's current big client -- and has been several times in the past. He's a big Hollywood producer, currently disentangling himself from a writer to marry Carrie Cartwright, the currently hot teen-queen actress. (Evans looks to have a good three decades on Carrie, but Ares & Aphrodite does its best to ignore that and focus on their individual personal issues. I thought that was fine; others may find it harder to ignore.)

Evans is Will's client; Carrie is Gigi's. So they're currently running into each other a lot. Will asked Gigi to go on a date with him -- she shot him down. So he proposed a bet: if Evans and Carrie do get married, she'll go out with him. And Gigi accepts.

That's the central thread of the plot -- one lawyer, one wedding planner, one too impetuous aging producer, one not-as-sweet-as-she-seems ingenue, and a few friends and hangers-on. It ends at the big wedding, at a mansion by the sea. And their bet is decided there.

They don't battle ninjas; they don't even save a movie from ruin. They're people living their lives and doing their jobs -- and those jobs are mostly giving honest, professional advice, to help their clients achieve what they want in the best way possible.

It's a sweet story, no bigger than it has to be, courtesy of Rich. Levens makes the art equally clean and transparent, like we're looking through a window into these people's lives, and this is how they must look at any moment.

Ares & Aphrodite is small -- but, as the old saying goes, it's also perfectly formed. We can always use more stories like that.

Oh, what a quaint house!

Aren't you a darling little man!

What an adorable book!

I'm going to try to avoid that pitfall today. But what I like best about this graphic novel by writer Jamie S. Rich and artist Megan Levens is that it's not trying to do too much. Ares & Aphrodite tells the story of one couple -- well, one potential couple -- and how they got together, if, eventually, they do get together enough for that to be a story.

In a world of comics that seem to want to be widescreen media-spanning epics, Ares & Aphrodite aspires to be a really good small movie, the kind made for a TV channel that churlish men avoid or that plays in that one theater two towns over. It's about two people, their professional connection, and a low-stakes bet they make with each other.

Will Ares is the top divorce lawyer in town. Gigi Averelle runs Aphrodite's, the most exclusive wedding-planning service in town. "Town," in this case, is Los Angeles, which would normally mean both of these two are massively important, with egos to match -- but they're both awfully normal and down-to-earth. Both seem to be somewhere in their thirties: old enough to have succeeded, old enough to want something better, young enough to still have time ahead of them.

Evans Beatty is Ares's current big client -- and has been several times in the past. He's a big Hollywood producer, currently disentangling himself from a writer to marry Carrie Cartwright, the currently hot teen-queen actress. (Evans looks to have a good three decades on Carrie, but Ares & Aphrodite does its best to ignore that and focus on their individual personal issues. I thought that was fine; others may find it harder to ignore.)

Evans is Will's client; Carrie is Gigi's. So they're currently running into each other a lot. Will asked Gigi to go on a date with him -- she shot him down. So he proposed a bet: if Evans and Carrie do get married, she'll go out with him. And Gigi accepts.

That's the central thread of the plot -- one lawyer, one wedding planner, one too impetuous aging producer, one not-as-sweet-as-she-seems ingenue, and a few friends and hangers-on. It ends at the big wedding, at a mansion by the sea. And their bet is decided there.

They don't battle ninjas; they don't even save a movie from ruin. They're people living their lives and doing their jobs -- and those jobs are mostly giving honest, professional advice, to help their clients achieve what they want in the best way possible.

It's a sweet story, no bigger than it has to be, courtesy of Rich. Levens makes the art equally clean and transparent, like we're looking through a window into these people's lives, and this is how they must look at any moment.

Ares & Aphrodite is small -- but, as the old saying goes, it's also perfectly formed. We can always use more stories like that.

Friday, August 24, 2018

Book-A-Day 2018 #236: The Dragon Slayer by Jaime Hernandez

As a first approximation, it's fair to say that anyone who writes more than five books will eventually do one for young readers. OK, we can think of some counterexamples (Henry Miller! Charles Bukowski!) and some people qualify only under the technicality that their books are now taught to teenagers, but it holds up most of the time, which is all you need for a rule of thumb.

This year, Jaime Hernandez, the cartoonist behind one-half of Love and Rockets, provided another datapoint to strengthen that rule of thumb: The Dragon Slayer, a book of retold Latin American folktales. He's been making comics for about forty years now, aimed at adults -- I was just reading a Hernandez book a few days ago with cartoon genitalia and everything -- but this one is not just from a publisher dedicated to comics for kids (Toon Graphics) but even includes contextualizing text features, like those book-report books you hated back whenever you were in school.

It's OK: that stuff is much easier to take if you don't need to write a report on it, adults often even enjoy learning new things -- well, the good kind of adults do -- and the text bits in The Dragon Slayer are both short and interesting. But, still, the whole thing is pretty darn educational. (So keep that in mind if you're a Hernandez fan who hears about it.)

The core of the book are three stories adapted and drawn by Hernandez in what looks like a slightly simpler version of his usual style: "The Dragon Slayer," "Martina Martinez and Perez the Mouse" and "Tup and the Ants." I'm personally fond of the last one, since the moral is that the lazy but smart third son will win out in the end, and I always have a soft spot for lazy protagonists. (The first story has a very vague moral that basically comes down to "be nice and helpful" and the second is the somewhat more specific "it's better to help than to run around being sad about something.")

Up front is an introduction by folklorist F. Isabel Campoy and at the end are four text pages left uncredited -- they don't seem to be in Hernandez's voice, but they could be by him, or by some editorial hand, or by Campoy. (My bet is on the middle choice: that would explain why there's no credit.) That backmatter includes a bibliography, a selection of story-starting phrases suitable for use by a young audience making up their own tales, and some light background on these three folktales and how they relate to Latin America.

Hernandez is always an engaging cartoonist, and his style adapts well to a younger audience. There's none of the bite of his best work here, though: he's not choosing nasty folktales, or ones with a sting in the tail (maybe because the audience for this book is quite young). The Dragon Slayer is deeply nice and respectable, which is something Hernandez hasn't always been with his more personal work -- I missed that, myself, and other Hernandez fans might as well.

This year, Jaime Hernandez, the cartoonist behind one-half of Love and Rockets, provided another datapoint to strengthen that rule of thumb: The Dragon Slayer, a book of retold Latin American folktales. He's been making comics for about forty years now, aimed at adults -- I was just reading a Hernandez book a few days ago with cartoon genitalia and everything -- but this one is not just from a publisher dedicated to comics for kids (Toon Graphics) but even includes contextualizing text features, like those book-report books you hated back whenever you were in school.

It's OK: that stuff is much easier to take if you don't need to write a report on it, adults often even enjoy learning new things -- well, the good kind of adults do -- and the text bits in The Dragon Slayer are both short and interesting. But, still, the whole thing is pretty darn educational. (So keep that in mind if you're a Hernandez fan who hears about it.)

The core of the book are three stories adapted and drawn by Hernandez in what looks like a slightly simpler version of his usual style: "The Dragon Slayer," "Martina Martinez and Perez the Mouse" and "Tup and the Ants." I'm personally fond of the last one, since the moral is that the lazy but smart third son will win out in the end, and I always have a soft spot for lazy protagonists. (The first story has a very vague moral that basically comes down to "be nice and helpful" and the second is the somewhat more specific "it's better to help than to run around being sad about something.")

Up front is an introduction by folklorist F. Isabel Campoy and at the end are four text pages left uncredited -- they don't seem to be in Hernandez's voice, but they could be by him, or by some editorial hand, or by Campoy. (My bet is on the middle choice: that would explain why there's no credit.) That backmatter includes a bibliography, a selection of story-starting phrases suitable for use by a young audience making up their own tales, and some light background on these three folktales and how they relate to Latin America.

Hernandez is always an engaging cartoonist, and his style adapts well to a younger audience. There's none of the bite of his best work here, though: he's not choosing nasty folktales, or ones with a sting in the tail (maybe because the audience for this book is quite young). The Dragon Slayer is deeply nice and respectable, which is something Hernandez hasn't always been with his more personal work -- I missed that, myself, and other Hernandez fans might as well.

Thursday, August 23, 2018

Book-A-Day 2018 #235: Star Wars: A Long Time Ago...: Dark Encounters by a whole bunch of people

Today's story is about reading procrastination, or about good intentions, or maybe just how there's more things we want to do in the world than there are things we have the time to do.

Fifteen years or so ago, Dark Horse was humming along with its Star Wars comics program -- a few things tied to the prequel trilogy, which was about to wrap up, but mostly in the "Extended Universe," in-continuity stories that stretched across comics and videogames and the novels Bantam and others published. Someone remembered that there was also an old series of Star Wars comics -- the ones from Marvel that ran from 1977 through 1986 and were solidly out of continuity by that point -- and decided to reprint them.

I guess they were pitched to the Science Fiction Book Club, where I worked at the time. I was the resident Star Wars guy then, reading and acquiring all of the novels and getting to go to a licensor showing of Phantom Menace a few years earlier. [1] I don't think we did them, but I ended up with copies of the first two collections, Doomworld and Dark Encounters.

At the time, I thought I'd be doing a lot of reading on the nice comfortable couch in our dining room/kitchen/maybe a great room if you squint. So the two Star Wars books, along with some other stuff, migrated to an end table next to that couch, and sat there. Somewhere in the middle, before this blog started, I did read Doomworld.

But Dark Encounters lingered, and wandered around the house, in search of a reading spot where I actually would read it. Eventually, it ended up on a shelf, which would have been the sensible place to begin, and I finally got to it -- forty years after the comics themselves and over fifteen since the book was published -- as part of this Book-A-Day push.

These stories are not part of any continuity anymore. They only vaguely qualified when they came out, since it was only the dawn of the Era Of Continuity, and it's clear whoever held the license issued occasional diktats to Marvel, asking them to tack over in this direction because the new movie was coming up, or to slim down the new additions and have the next big plotline be set on Tatooine again.

But even that vague, OK-maybe-it's-sorta-canon sense of the original comics was firmly jettisoned first by the Extended Universe (which, as far as I can tell, is mostly called that in retrospect -- at the time it was just a bunch of other Star Wars stories in different media) and then by whatever we're calling the spiffed-up Nu Wars continuity where Han and Leia only had one mopey son rather than three odd kids. So these stories are doubly out of continuity -- they're not even part of the old one, that various sectors of the Internet are loudly proclaiming is obviously better than this new version with way too many icky girls and not enough boys playing with their lightsabers.

And, frankly, these are odd stories: very comic-booky, obviously done quickly to deadlines and trying to spin out what was a fairly thin thread from the first Star Wars movie. (At this point, it was still called Star Wars. Please remember that.) If none of the ideas from these comics -- the giant gambling space station The Wheel, ray shields, the villainous and aristocratic Tagge family, cyborg bounty hunters, Imperial industrial planets, the idea of the Empire as a long-running thing with a family one could marry into, the winged Sky'tri people of Marat V, the Sacred Circle religious organization -- turned out to have anything to do with George Lucas's actual future Star Wars stories, well, how could any of us have known? (George didn't know himself, despite all of the many "I meant to do that" retcons since then.)

Dark Encounters collects issues 21 to 38, and the first Annual, of that Marvel series. Those comics originally appeared from March 1979 through August 1980 -- Empire was in production for most or all of that time, but how much of the details flowed out to the comics team is harder to say. These were the days before tight licensing integration, in a world where communications were slower and less ubiquitous than now. Stuff just happened.

The comics here are mostly written by Archie Goodwin, with Chris Claremont tackling the Annual. Carmine Infantino draws nearly all of the issues, inked by Bob Wiacek most of the time and Gene Day the rest. (Mike Vosburg and Steve Leialoha did the Annual with Claremont.) The very last issue here much have some kind of interesting story behind it: issue 37 proclaims that the next issue will start the Empire adaptation, but the actual issue 38 has a shorter story "written" by Goodwin but "plotted" by penciller Michael Golden, which smells like a last-minute rush job to me. The issue (inked by Terry Austin) is also very much a one-off fill-in, of the "hey! did we tell you this story? it happened a little while ago, in between other stories..." style. And then it, too, says the next issue will begin the Empire adaptation, which actually did happen.

Characters often look off-model here, particularly Chewbacca, who has a flesh-colored face for a lot of the book. Whether they act off-model is a more complicated question: you have to consider only the original Star Wars movie, and that doesn't giver us a lot of guidance. But they're all pretty recognizable as the people they kept being in the later movies -- depth of characterization is not really a George Lucas core concern.

So these are weird, funky '70s Star Wars stories, set in a universe that's vaguely like the later Star Wars universes, but not all that much. Sadly, the giant green bunny Jaxom doesn't show up in this book -- I think he was in the first collection -- but we do have a planet of blue-skinned flying people to compensate. (Frankly, a lot of this Star Wars feels more like the 1980 Flash Gordon than like what Star Wars turned into.) The core audience, obviously, is people who were there at the time, but there's appeal to anyone who likes the oddball corners of space-operatic universes.

[1] True fact: I only got to go to two movie screenings because of the SFBC. One was Phantom Menace and the other was Batman and Robin. So, yeah, the glamor was real.

Fifteen years or so ago, Dark Horse was humming along with its Star Wars comics program -- a few things tied to the prequel trilogy, which was about to wrap up, but mostly in the "Extended Universe," in-continuity stories that stretched across comics and videogames and the novels Bantam and others published. Someone remembered that there was also an old series of Star Wars comics -- the ones from Marvel that ran from 1977 through 1986 and were solidly out of continuity by that point -- and decided to reprint them.

I guess they were pitched to the Science Fiction Book Club, where I worked at the time. I was the resident Star Wars guy then, reading and acquiring all of the novels and getting to go to a licensor showing of Phantom Menace a few years earlier. [1] I don't think we did them, but I ended up with copies of the first two collections, Doomworld and Dark Encounters.

At the time, I thought I'd be doing a lot of reading on the nice comfortable couch in our dining room/kitchen/maybe a great room if you squint. So the two Star Wars books, along with some other stuff, migrated to an end table next to that couch, and sat there. Somewhere in the middle, before this blog started, I did read Doomworld.

But Dark Encounters lingered, and wandered around the house, in search of a reading spot where I actually would read it. Eventually, it ended up on a shelf, which would have been the sensible place to begin, and I finally got to it -- forty years after the comics themselves and over fifteen since the book was published -- as part of this Book-A-Day push.

These stories are not part of any continuity anymore. They only vaguely qualified when they came out, since it was only the dawn of the Era Of Continuity, and it's clear whoever held the license issued occasional diktats to Marvel, asking them to tack over in this direction because the new movie was coming up, or to slim down the new additions and have the next big plotline be set on Tatooine again.

But even that vague, OK-maybe-it's-sorta-canon sense of the original comics was firmly jettisoned first by the Extended Universe (which, as far as I can tell, is mostly called that in retrospect -- at the time it was just a bunch of other Star Wars stories in different media) and then by whatever we're calling the spiffed-up Nu Wars continuity where Han and Leia only had one mopey son rather than three odd kids. So these stories are doubly out of continuity -- they're not even part of the old one, that various sectors of the Internet are loudly proclaiming is obviously better than this new version with way too many icky girls and not enough boys playing with their lightsabers.

And, frankly, these are odd stories: very comic-booky, obviously done quickly to deadlines and trying to spin out what was a fairly thin thread from the first Star Wars movie. (At this point, it was still called Star Wars. Please remember that.) If none of the ideas from these comics -- the giant gambling space station The Wheel, ray shields, the villainous and aristocratic Tagge family, cyborg bounty hunters, Imperial industrial planets, the idea of the Empire as a long-running thing with a family one could marry into, the winged Sky'tri people of Marat V, the Sacred Circle religious organization -- turned out to have anything to do with George Lucas's actual future Star Wars stories, well, how could any of us have known? (George didn't know himself, despite all of the many "I meant to do that" retcons since then.)

Dark Encounters collects issues 21 to 38, and the first Annual, of that Marvel series. Those comics originally appeared from March 1979 through August 1980 -- Empire was in production for most or all of that time, but how much of the details flowed out to the comics team is harder to say. These were the days before tight licensing integration, in a world where communications were slower and less ubiquitous than now. Stuff just happened.

The comics here are mostly written by Archie Goodwin, with Chris Claremont tackling the Annual. Carmine Infantino draws nearly all of the issues, inked by Bob Wiacek most of the time and Gene Day the rest. (Mike Vosburg and Steve Leialoha did the Annual with Claremont.) The very last issue here much have some kind of interesting story behind it: issue 37 proclaims that the next issue will start the Empire adaptation, but the actual issue 38 has a shorter story "written" by Goodwin but "plotted" by penciller Michael Golden, which smells like a last-minute rush job to me. The issue (inked by Terry Austin) is also very much a one-off fill-in, of the "hey! did we tell you this story? it happened a little while ago, in between other stories..." style. And then it, too, says the next issue will begin the Empire adaptation, which actually did happen.

Characters often look off-model here, particularly Chewbacca, who has a flesh-colored face for a lot of the book. Whether they act off-model is a more complicated question: you have to consider only the original Star Wars movie, and that doesn't giver us a lot of guidance. But they're all pretty recognizable as the people they kept being in the later movies -- depth of characterization is not really a George Lucas core concern.

So these are weird, funky '70s Star Wars stories, set in a universe that's vaguely like the later Star Wars universes, but not all that much. Sadly, the giant green bunny Jaxom doesn't show up in this book -- I think he was in the first collection -- but we do have a planet of blue-skinned flying people to compensate. (Frankly, a lot of this Star Wars feels more like the 1980 Flash Gordon than like what Star Wars turned into.) The core audience, obviously, is people who were there at the time, but there's appeal to anyone who likes the oddball corners of space-operatic universes.

[1] True fact: I only got to go to two movie screenings because of the SFBC. One was Phantom Menace and the other was Batman and Robin. So, yeah, the glamor was real.

Wednesday, August 22, 2018

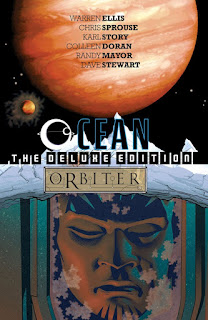

Book-A-Day 2018 #234: Ocean/Orbiter by Warren Ellis and various artists

The romance of monkeys in tin cans continues to elude me. It was one of my pet peeves back when I was working at the SFBC -- an endless stream of stories, all by men (it was always men) who imprinted on an Apollo launch early, with another piece of special pleading about how Man was Destined to Go To The Stars because it was His Destiny Goshdarnit and We Can't Put All Our Eggs In One Basket and The Frontier Breeds Real Men and Man Must Go Ever Onward and similar piffle.

I thought I'd left that all behind a decade ago when I was cast out of paradise lost my SF job, and that was one of the few bright spots of the transition. [1]