Genre fiction in comics tends to be

straightforward: it explains the world and the stakes up front, then sends a generally pretty obvious Protagonist off to Do the Thing, which far too often is Saving the World.

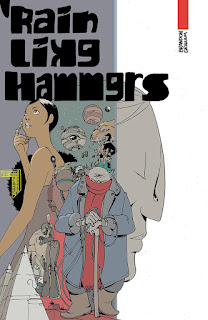

Brandon Graham, in his afterword to Rain Like Hammers, describes that as being like a Japanese game show where the goal is to get someone to eat a hot dog as soon as possible after waking up. And he's not into speed-eating hot dogs.

Graham's stories tend to start in a more leisurely fashion. His camera-eye is focused, but not insistent. Hey, look over here, it says. Something is going on; I wonder what it is?

Rain Like Hammers collects a five-issue comics story - the issues were published in the first five months of 2021, and this collection came out in August. They're long issues, too - the book is unpaged, but I think they're 48 pages each. So my first question is: how serialized was this? Clearly, Graham created it in five chapters, but I really doubt he did that during those five months. But those afterwords - there's one for each issue, two pages each of sketchbook-style comics - do show the process of making the book; he seems to have made it in order, finishing each page in turn and not going back to rework based on better ideas later.

At one point he mentions his initial plan was to have five loosely-connected single issue stories - maybe, I think, ones that all came together in the final issue? - and that's clear in the transition between the first two issues, which are entirely different, about entirely different people in entirely different places. But, in the end, this is mostly one story, seen from a couple of angles, with a second story as a way in and a bit of parallax later.

We start out in a mobile city, on some alien planet in some future. Eugene is new in Elephant City: he finished his schooling recently, and came here on purpose, to do some keeping-the-city-running job that Graham doesn't explain in detail. Eugene is a bit lonely, finding his footing in a new place and new to adulthood. But he seems like a sensible, devoted person: we think will be OK, we want to trust him, he hope he will do well. His story for the first issue is mostly low-key, but something from outside this world is causing trouble for many of the animal-named crawling cities, and we see a little of that here.

The second issue begins what then seems to be the main story, and we may wonder what happened to Eugene, for many pages. (We will find out.) A supercriminal, Brik Blok, is heading to Sky Cradle, a space habitat of some kind that is the seat for the rulers of this part of human space: a group of self-selecting immortal families. We think he is dangerous, we think he is exciting, and we are not entirely sure if we are on his side.

What Brik Blok is coming to do on Sky Cradle is something we learn quickly, but we learn more and more details over time: we learn it iterated, first the headlines and then the depths, eventually getting to things Brik Blok didn't know himself. Brik Blok's initial plans, whatever they were, fail before he even reaches Sky Cradle: he's in a different body, in an society he doesn't know well, with a new uncertain ally or friend.

Brik Blok is coming to save El. Or maybe retrieve her, or maybe support her. She is young and smart and, we believe, on the side of right. She's part of a program of "candidates" for immortality: they are tested and twisted and transformed to become more of the ruling class. We start to think we don't like this ruling class, and start to feel more positively towards those who resist. We quickly learn she did not choose to join this program...though we learn more details later.

Rain Like Hammers is mostly the story of Brik Blok and El. Two people fighting against the power structure, or trying to - both with incomplete information at this point in their lives. (This is the kind of SF where people can live a very long time - maybe even if they're not officially one of the "immortals" - and who they once were and what they once did could be forgotten or lost or mislaid.)

They do not foment a revolution. They are not even trying to topple the immortals: their aims are smaller, more specific than that. As I said at the beginning, this is not that kind of comic: they are not going to Do the Thing, not going to Save the World.

But they, and Eugene, may be able to save themselves, and get away.

Graham tells this story from the inside, with pages full of quiet moments and strange details of this far-future world. His SF is always deeply distinctive, with things he never explains, a big lived-in universe full of odd creatures and people, all living their own lives and wandering across his pages. He tones down the wordplay these days, especially in more serious, grounded stories like this one, but there's still some of that joy in the complications of language.

SF that requires the reader to think about it and make up his own mind about it is rare in comics - it's not all that common in prose, frankly. That's what Graham does; that's what this is. Any reader who likes that kind of SF should check it out, or anyone who likes stories with a bit of gnarl to them.