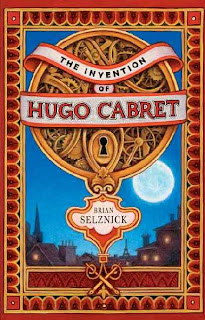

The somewhat-controversial 2007 Caldecott winner was published as a novel, but it really is an overgrown picture book -- the biggest, longest picture book in history -- which makes the Caldecott win more understandable.

The somewhat-controversial 2007 Caldecott winner was published as a novel, but it really is an overgrown picture book -- the biggest, longest picture book in history -- which makes the Caldecott win more understandable. It's just under six hundred pages long, but about half of that is art -- and many of the pages with words on them have only a few lines of text. (Hugo Cabret is quite old-fashioned as a picture book; pages -- spreads, actually -- have either words or pictures on them, but not both.) Some people have compared Hugo Cabret to a graphic novel, but the art is more like a picture book -- large drawings, placed to dominate or fill a page -- there's no panel-to-panel transitions on individual pages. I read it in about an hour and a half; I'd expect even a slow reader wouldn't take more than three hours, unless she intensely dawdled over the art.

Hugo is an orphan in Paris in 1931, living in the walls of a train station, keeping the clocks wound, stealing food and clothing, and avoiding the dreaded Station Inspector. His father was killed in a museum fire, but he's trying to complete his father's last project -- the restoration of a man-shaped automaton at a writing table. Unfortunately, to repair the automaton he needs parts, and to get those parts he steals mechanical toys from a handy shop in the station...until, one day, the proprietor catches him.

The proprietor and his adopted daughter Isabelle get caught up in Hugo's story, and, as one might expect, they have a deep and hidden connection to Hugo. All is revealed eventually, and everything wraps up more neatly than I'd prefer, though it is appropriate for a book for younger readers like this. The story ends up being in large part an excuse for Selznick to get into the history of a person he greatly admires, and to go on about automatons, another subject he's very interested in.

Without giving away important plot points, there's not much more I can say about the story. It's nice, but slightly flattened, the way some stories for younger readers are. The art is more cinematic than graphic-novelish, with obvious tracking shots moving across several pages. I think those effects work decently here, but comics have built up a visual language of their own over the last century or so, which can achieve many of the same effects without taking twenty pages to do so. There's nothing wrong with the way Selznick does it -- and his art is very nice -- but there's something odd and old-fashioned about Hugo Cabret, as if it were a book from 1931 instead of just being about that time.

No comments:

Post a Comment