This post lists all of the books I read in the month of October 2015. In happier times, I had links to longer posts about each of those books, but these days it's all I can do to write a couple of paragraphs here about them and try not to be too dismissive or slapdash. But, as always, we only can do what we can do.

So here's what I read in October, with the hopes that something hear piques your interest, and you find something wonderful and new to read:

Mike Mignola, John Arcudi, and Alex Maleev, Hellboy and the B.P.R.D: 1952

Since Hellboy is dead in his main series -- that doesn't stop him, since he's basically a prince of hell to begin with, but it does keep him from being on Earth, at least for the foreseeable future -- and perhaps because the main B.P.R.D. book is so gloomy these days, what with the end of the world and all, someone clearly thought there was room for a slightly happier, more positive killing-Nazi-monsters comic in the Hellboy universe. And this is it.

There have already been a number of stories about Kid Hellboy -- most notably The Midnight Circus and "Pancakes" -- so this isn't exactly Hellboy: Year One, but that's clearly the intention. This is the first major case that a basically-grown Hellboy (eight years on Earth but the size of an adult) went on, and the story of the first time he punched monsters so hard it saved the world from Nazis.

It's less continuity-heavy than most of the Hellboy-iverse stories these days: yes, it does have Nazis and references to Rasputin, but it's not caught up in multiple iterations of the Black Flame and Abe Sapien's continuing metamorphosis and everything else like the modern-day stories are. So this could be a decent starting point for Hellboy for new readers -- though a new reader would be much better served to just jump into one of the earlier all-Mignola Hellboy stories instead.

And if you wanted more Nazi-monster-punching and less angst over giant creatures destroying the world in your B.P.R.D. stories, you are definitely in luck here.

Alan Moore and various artists, Miracleman Book 2: The Red King Syndrome

This was the messy stretch of the original series, a fact that doesn't get mentioned a lot in the gushing appreciations of Miracleman. The stories collected here span the end of the Warrior era and the first new issues from Eclipse, and also span a variety of artists -- Alan Davis, John Ridgway, Chuck Austen, and Rick Veitch. Davis and Ridgway are very suitable for the series, Veitch not as much so, and Austen was frankly a mistake.

(Austen's come in for a lot of abuse over the years, mostly undeserved, but it's definitely true that he's had horrible luck whenever he goes into the world of superheroes, getting into projects that don't mesh well with his talents and creating work that doesn't quite line up with the rest of that particular fictional universe.)

So this volume is very uneven, artwise, which highlights how much Moore overwrites. That's effective a lot of the time, when he has a strong collaborator and the art is equally strong and distinctive and striking. But with Austen's fairly generic superhero work and even Veitch's scratchier take on the same thing, it feels like overwriting, and the reader can see Moore straining for effect. He gets there, most of the time, but the strain is evident.

The story closes out most of the story threads from the first volume, with Miracleman confronting his creator, Gargunza, and seeing the birth of his daughter Winter. But Winter herself will be a major thread in the next set of stories, and there's a mysterious pair of entities -- clearly not human, though they look that way -- poking around and getting closer to our main plot. This is the piece of Miracleman that could greatly benefit from a reworking: give the original Moore scripts to a single strong artist, and have it all redone. That will never happen, of course, but it does leave this middle volume as a bit of a blemish on the larger story.

Alan Moore and John Totleben, Miracleman Book 3: Olympus

Alan Moore and John Totleben, Miracleman Book 3: OlympusSpeaking of overwriting....

Superhero comics have been a friendly home for purple prose since at least Stan Lee, with captions cluttering up pages to declare things that we should be able to figure out by looking at the pictures. The 1980s were the high-water mark of captions, and Moore the modern writer most prone to using them indiscriminately -- and this last major Miracleman story from Moore is a feast of captions, with every last event and moment narrated to within an inch of its life.

It almost works -- it does work, to some degree. But, especially twenty-plus years later, the reader looks at the sea of overwrought words and wishes that someone, whether Moore himself or some stronger editor, was able to tone down the flood of six-dollar words and complex sentences and allow some images to stand for themselves. Olympus is beautiful and horrible in turn, as fitting the events within it, and John Totleben was probably the best artist Moore ever worked with. Totleben's work is stunning here, precise and detailed and flashing across the page in unique, inventive layouts. It doesn't need all of those words, and all of those words tend to drag down the art. But that was the '80s; the era when everything had to be bigger, to be more, to fill every possibility.

Moore's utopianism is pleasant, but less compelling on a story level than his stories of battling gods -- luckily, though the utopianism is the point of Olympus, it also contains his single best battling-gods scene, which is also the ultimate superhero fight story. After that, there was nothing more to say -- though, of course, dozens of writers have been saying that nothing for the twenty-five years since.

If you still care about superhero comics, you need to read Miracleman and incorporate it; it's that imposing and influential and impressive. Pity about all the words, though.

Richard Kadrey and the Pander Brothers, Accelerate

Kadrey is an oddball SF writer who could be called a second-wave cyberpunk if you wanted to be incredibly reductive, who's popped in and out of the field with successively stranger projects over the past three decades. The Pander Brothers illustrated one excellent and groundbreaking Grendel story for Watt Wagner twenty years ago, bringing a visual style and energy inspired by fashion illustration, and then mostly disappeared themselves. In 2007, they found each other, somehow, and brought out a stylish, cyberpunky story of "tribal" young people in the usual grotty near-future, full of drugs and oppressive adults and messianic leaders and lots of running and fighting.

It's sadly less than the sum of its parts, ending up dull and derivative and obvious and predictable, with a heroine who mostly runs around following other people and a worldview borrowed from the worst early stories of William Gibson. The Pander Brothers do make it all look interesting, and Kadrey gets some spiky dialogue in there in spots. But it's third-tier cyberpunk at best, the kind of thing that was tired in 1987, let along twenty years later.

Christophe Blain, Isaac the Pirate, Vol. 2: The Capital

See my review of the first volume, from last year, for more details on Isaac and his pirating ways.

When I close my eyes and picture "Eurocomics," it's something like this I think of: lots of dark panels on a page, a story full of adults with conflicting motivations (with each other and with themselves), action that doesn't really solve problems, sudden and irrevocable changes (including random deaths), stylish art that usually helps tell the story, inconclusive endings that will probably lead to more stories but don't have to.

This particular series is a bit more cramped -- both in the art and the storytelling -- than I'd prefer, but Blain draws great grotesque figures and writes intriguing things for his people to do. I still think Gus and His Gang is a better book, but I'd love to see more Blain, and I hope he's still working away in France and that his books will eventually make it over to me in English.

Andrew Helfer, Kyle Baker, and Marshall Rogers, TThe Shadow Master Series, Vol. 2

Andrew Helfer, Kyle Baker, and Joe Orlando, The Shadow Master Series, Vol. 3

I'll cover both of the collections of Helfer-Baker Shadow stories together -- Rogers and Orlando did one sidebar story (each), but the main bulk of each of these books is the manic, wild, thrilling adventures of the Shadow in 1980s New York (and elsewhere) as written by Helfer and drawn by Baker. The rumor at the time was that Street & Smith, owner of the Shadow, shut down this series suddenly because they hated the direction Helfer and Baker were taking it -- that may be a self-serving legend, but it's definitely plausible: these are nutty, wild stories, and it would be easy to see a staid old licensor being appalled by them.

Helfer writes the Shadow as a nearly supernatural being, almost unstoppable but stuck in a world full of random events and unstable people, focused entirely on his mission but barely able to keep up with one crime-eliminating mission at a time when crime is so multifarious and ubiquitous. His agents are competent enough, in their own colorful ways, but they're all oddballs and misfits, as likely to run off following personal hobbyhorses as to actually do what the Shadow orders. It's a vision of a world of chaos, a world that cannot be mastered or controlled, and of the one man who is almost strong enough to impose his will on that world. Helfer's Shadow can stop any individual crime with ease, but that means very little in a world this big and this frantic. Helfer's take is funnier than usual for the Shadow, but the underlying idea is the same -- his Shadow doesn't joke or laugh (except for that mocking cry punctuated by automatic gunfire), but lives in a world that is absurd and makes other people laugh.

And Baker was a perfect collaborator for Helfer, even better than Bill Sienkiewicz, who illustrated the first story arc. Baker's art at the time was just a few clicks past standard house-style, with expressions that much broader and gestures that much wilder. He drew the barely-contained chaos that Helfer wrote, making it solid and real and giving Helfer's nutty characters equivalent visuals, culminating in the magnificent hair of Twitch, defying gravity and seeming to have a life of its own.

Each of these books collects one long story, plus some extras. (Volume two opens with a one-shot story illustrated by Rogers; three includes the two annuals in the back: the first a separate story illustrated by Orlando, the second a sidebar to that volume drawn by Baker.) Those stories are twisted and weird and funny and odd, driven by dialogue and coincidence and quirky villainy and random chance. It doesn't really end; Helfer and Baker were clearly planning for more stories when the plug was pulled -- whoever pulled it. But they got this far, and made two big books full of crazy Shadow stories, which is something to celebrate.

Jeff Lemire, Sweet Tooth Vol. 1: Out of the Deep Woods

I've mentioned before that I like Jeff Lemire's indy work a lot, but haven't kept up with the books he's done for the Big Two comics companies. (I'm old, and have seen a lot of good writers head into that meat-grinder to do absolutely mediocre work -- and I don't really care about superheroes to begin with.) But Lemire did a creator-owned series for Vertigo from 2009 to 2013, and I had the first volume sitting on a shelf for a few years, waiting for me to catch up to it.

Reader, this is that book. (But you figured that out already, didn't you?)

Sweet Tooth is set in post-apocalyptic America: seven years ago, the usual horribly virulent and inexplicable disease killed most of mankind very quickly, and all of the children born since then are human-animal hybrids. (So this is definitely not hard science fiction.) One of those kids is Gus, about nine as the story opens -- somewhat older than is supposed to be possible, based on the accepted story. Gus was raised by his father in a remote cabin after the death of his mother, and hasn't seen another human his entire life. But, when his father dies, the outside world finds Gus, and sets him off through a depopulated world where his find are commodities at best and targets at worst.

This is clearly Lemire trying to work in a more commercial direction than usual, and he's mostly successful at it, though it's less Lemire-ish than his other books I've read. I'll probably keep up with the series, but I don't feel a huge need to: this is a solid Vertigo series, with all of the strengths and weaknesses of that style, but nothing more exciting than that.

Mike Mignola, et. al., Abe Sapien, Vol. 6: A Darkness So Great

Mike Mignola, et. al., Abe Sapien, Vol. 6: A Darkness So GreatAbe is still on his wander through post-apocalyptic America -- this particular apocalypse caused by giant magical monsters, the underground race of frog creatures, and possibly the failed ascent of Hellboy to the throne of Hell. But this story saw him settle into a small Texas town for a little while, for what seemed to be relative peace at first.

Things go horribly wrong, of course: that's a decent four-word description of every B.P.R.D. story, and Abe's adventures fall into that paradigm. I am beginning to wonder how much further things can continue to go wrong; it seems that there will be no people left for Abe to witness dying horribly at the hands of supernatural creatures if this goes on much longer. Previous storylines have destroyed entire cities (Seattle, New York) and even countries (the UK), so perhaps killing much of a small town is actually a de-escalation. But it feels to me more like this is who's left: and we'll be down to individual wanderers within another couple of storylines.

What I'm saying is: I hope Abe finds something. And I hope Mignola and Allie have a plan that goes beyond showing the death of every single human being, one at a time. That is already getting tedious, though Abe's journey is still compelling -- as long as a reader can believe that he's heading towards something that he will eventually find.

Justin Pierce, The Non-Adventures of Wonderella: A Hero for All Seasons (10/20)

This was a kickstarted collection of the webcomic of the same name: the book itself doesn't explain itself, but the kickstarter page says that it has all of the strips for the prior four years, and that it's the third collection of the strip. It also had a new twenty-eight page prequel story, which is a nice thing.

I've been reading Wonderella for a while, and it's the kind of jaundiced, funny piss-take on superheroes that's as close as I want to come to the real genre these days. Wonderella is a legacy hero: she's got this job because her mom had it, but she's not all that into it. And her villains are very silly when they're not actively stupid.

Why do I like this strip? Well, to quote one punch-line, "Sometimes half-ass is exactly the right amount of ass." Sounds good to me.

Paul Pope, The One Trick Rip-Off + Deep Cuts

In 1995, Paul Pope created a serial for Dark Horse Presents, about two young lovers trying to steal from the gang that the boy belonged to and get out of their miserable lives. That went about as well as similar ideas always do, with lots of running and shooting and screaming and bad decisions and deaths and near-deaths.

And it took nearly twenty years for that story to be collected, for no clear reason I can see. But, when it finally was collected, The One Trick Rip-Off was combined with fourteen short stories by Pope from the same era (roughly: 1993 to 2001). And this is that book.

The other stories are more artsy and quirky than the main feature: Pope does straightforward action now and then, but he's always been more interested in the weird and the odd. No one else draws like Pope, and his pages are uniquely gorgeous in their inky grotesques. So getting nearly three hundred pages of "lost" Pope comics from his most experimental and weird period is a big treat. And that's exactly what this book is.

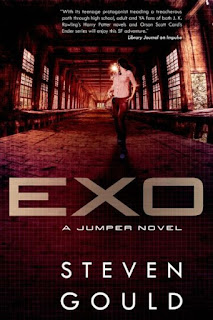

Steven Gould, Exo

Long ago, when the earth was young and everything was still possible, a young writer came up with an exciting new take on the Wild Talent novel, called it Jumper, and it was his first novel. It was also pretty damn good. A young editor read that book, and bought it for a bookclub known by its initials, and was excited to see each new book by that writer afterward.

(That's Gould and me, for the terminally thick among you.)

Jumper led to the direct sequel Reflex, to an unfortunately bad movie, and to the movie-influenced Jumper: Griffin's Story. Some years later, it also led to Impulse, a new novel narrated by the daughter of the hero of Jumper. And then, earlier this year, Millicent "Cent" Rice returned in Exo, the story of how she decided to use her ability to teleport to go to space.

I don't want to get into the plot of Exo here: it's not a plotty book, and Gould's greatest strength has always been in the voices of his lead characters and the life he gives to them and their worlds. You don't read Gould to flip pages quickly; you read him because he tells great stories about interesting people that you want to like and see succeed. And that's the case for Cent as well.

But you can read this without knowing any of the previous books at all. Reading Impulse would be nice, but it's not necessary at all. And Exo makes a great SF novel to give to teens interested in SF -- maybe particularly for kids with an interest in space piqued by a little thing called The Martian.

(And I continue to be amused at the way that Gould builds his world: as far as I can tell, this whole series is still completely consistent with my old claim that it's the secret backstory of The Stars My Destination.)

Jacques Tardi and Jean-Patrick Manchette, Like a Sniper Lining Up His Shot

This was the second "collaboration" between crime novelist Manchette and graphic novelist Tardi -- the noun is in scare quotes because Manchette was dead before Tardi began work on their first collaboration, West Coast Blues. It's possible to work with a dead man, but the conversation will only go in one direction.

Martin Terrier is a hitman who wants to retire: he has enough money, he's had enough killing, and he hopes to reunite with an old girlfriend. But it's never that simple, is it? And that leads to the usual web of cross and double-cross, of one last job and one more set of complications, of people who may be willing to help Terrier and people who can only benefit from his death.

This is as black, and as bleak, as noir ever gets -- a dark story about a dark man in a dark world, ably brought to life from Manchette's tough narration through Tardi's panels of sudden violence and unexpected changes.Crime-fiction fans don't wander into graphic novels as often as SF people do, as far as I can see, but they would be well-served to track down the Manchette-Tardi books.

Keith Colquhoun and Aun Wroe, The Economist Book of Obituaries

People die every week. (Every day, every minute, but that's beside the point.) But the British weekly magazine Economist (which insists on calling itself a newspaper, because what kind of world would we live in if a British institution weren't terminally quirky?) focused entirely on the living until 1995.

At that point, though, its editors were convinced that one carefully-selected obituary a week wouldn't ruffle the feathers of its world-dominating readership, or put them off their capital-accumulating ways too much. And so the "newspaper" started doing that: running one obit a week, for one carefully chosen person who just died, politicians and scholars and writers and leaders and artists and businessmen -- all of them celebrities of a sort, to the right sort of people.

This book collects about two hundred of those obituaries, from the first decade and a half of their existence -- Colquhoun wrote them from '95 to '03, and Wroe took over at that point. It tends to a lot of third-world political leaders -- the father of his post-colonial country here, the head of an insurgent movement there -- and the more colorful sort of tycoons, as you'd expect. Each essay is good, and each person had a life interesting enough to spend two pages reading about. It's a scattershot history of various pieces of the world, but sometimes that approach is as good as something more focused.

And that was October. November will follow shortly -- at least, that's my hope and plan. We'll see what actually happens.

No comments:

Post a Comment