How do we know who did anything? If they did it in public, there's that, of course. But if taking credit for a work was discouraged, how do we tell, years later, after everyone is dead, exactly how something came to be?

Bluntly, we don't. Art experts talk about "the studio of X" and insist that this one painting is clearly by the master because the gallery auctioning it is paying their fee because they are experts and can tell these things. With comics, the auction houses have less power, and are selling things clearly by Big Names anyway, so the process - I think - is clearer and more honest. But it's still a case of "artist X got paid for pages turned in on this date, which we're 99% sure is this story" and "the inking in story Y has these elements, so I know it was by That Guy."

There's been a lot of that, especially on the art side, in comics criticism. It is much easier to discern a artist's characteristic brushwork than a writer's characteristic motifs, particularly in such a cliché-ridden field as mid-century comics. So we're in the position, after a few decades of scholarship digging out the details of the decades before that, where we know, with a reasonable degree of certainty, who drew things without having anything like that certainty about who wrote them.

Since the writing comes first - no matter the breakdown of work, all the way to Marvel Method - that's a huge hole. And comics scholarship sometimes just shrugs its shoulders and kicks dirt over the question.

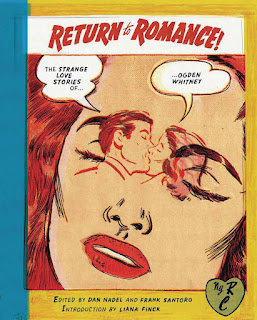

I didn't realize that was the case with Return to Romance! The Strange Love Stories of Ogden Whitney until I got to the afterword by co-editor Dan Nadel. (The other editor is Frank Santoro.) In the course of mostly writing about how this book came to be, we get this blunt assessment:

But actual writing credits are rare in ACG comics, and so it's impossible to know which, if any, of the present stories were written by [editor Richard] Hughes; his assistant editor, Norman Fruman; any number of freelancers passing through the office, or Whitney himself.

The book treats those stories, in the end, as if they were written by Whitney, since it's a book about Whitney. That is an entirely reasonable publishing decision. The stories do have a consistent tone and style...but Nadel and Santoro edited this selection of nine stories out of some unknown larger number of Whitney-drawn stories from a five-year period. Is it possible they dug out the nine best stories written by some other person - or even the nine only stories written by some other person - and that they're reacting to that person's style and concerns?

Yeah, maybe. But so what? What difference would it make, either way? Whitney is dead, Hughes is dead, Fruman is dead, and I assume all of those unnamed freelancers and unmentioned office workers are, too - these stories were made and published about sixty years ago. We are never going to know for sure. Why not attribute them to Whitney, for simplicity if nothing else?

Something in me wants to think a woman was involved centrally somehow. Oh, sure, I know romance comics were mostly made by men for teenage girls: all comics of the era were made mostly by men for teenagers of various kinds. But whoever wrote these stories, Whitney or otherwise, had a better sense of human motivation that most stories for third-tier companies, and the women in these stories, though driven by plots usually along familiar lines, are more individual than the standard comics ingenue, quirky and cranky and real in odd ways.

The men, oddly, are sometimes just as neurotic and messy - there's a guy afraid of everything, and a boxer shattered when he kills someone in the ring - but not quite as consistently. Men are the object of a romance story, so they can be more generalized, less specific, and there's a bit of that here.

Again, I don't know. I will never know. I want to believe a woman was somewhere in the mix, and not just that some man was really good at seeing women as people, but it's purely an act of faith on my part. My wishful head-canon is that some young woman in the office - probably a secretary in that era - wrote a few scripts, which Whitney turned into these stories, and then she went on to a fabulous life doing something else entirely different.

What we do have here is nine stories of romance. Drawn by Ogden Whitney, in that solid style comics fans know best from Herbie. Romance is even more suited to Whitney's artistic muse than fantasy was: his panels and pages have an Eisenhower-era solidity, almost drabness to them. If ever a man was born to draw tasteful living rooms and functional office suites with flat-color backgrounds, it was Whitney. His people are real, not glamorous - attractive when they're supposed to be without being beautiful at any point. The first story here centers on a photographer and his models, which is not quite the right cast for a Whitney story: I never get the sense any of his characters are pretty enough for a life like that. Whitney characters do clean up well: they can be the best-looking person in the world for the one they fell in love with. They're like you or me in that, and not like a pretty pin-up.

The plots are reasonably complicated for stories that run eight or a dozen pages: girl meets boy, girl either likes or hates boy, complications ensue, girl gets boy. Sometimes the narrative follows her, sometimes him. My sense is that the action that brings the two together is hers, nearly always - as it should be in stories for a female audience. And those complications can get complicated, as they should: these are often heavily-narrated stories, with a lot of dialogue and business.

These are psychologically complex people, as much as they can be in short comics stories. Some are neurotic, many are insecure about themselves, all have a yearning hole that can only be filled by one special person. They are romance stories.

These are fascinating, gnarly, interesting stories. I would not call them "great," but they're all at least "good" - professional, smart, quirky, specific. I have no idea how teenage girls in the early '60s reacted to them: these stories are about regret and insecurity and obsession and hate as much as they are about love; they seem aimed at an audience with a little more experience of life. But I am never going to say that a story being deeper, more resonant, or thoughtful is a negative, and I won't do that here.