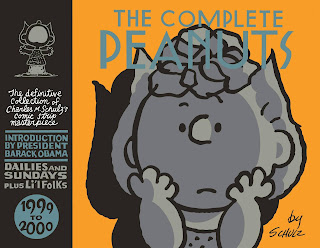

This is the end; this is not the end.

This volume

finishes up Fantagraphics' decade-plus reprint project covering the

entirety of Charles M. Schulz's fifty-year run on Peanuts, with

the last full year of strips and the few in early 2000 that Schulz

completed before his health-forced retirement and nearly simultaneous death. (Sunday

strips are done six to eight weeks early; his last strip appeared on the

Sunday morning of February 13, and he died the evening before, in one

of the most perfectly sad moments of timing ever.)

So that's the end.

It's also the beginning: also included in this book are all of the Li'l Folks strips that Schulz created for the St. Paul Pioneer Press

from 1947 through early 1950, and which he eventually quit when his

attempts to move it forward were turned down, freeing him to rework much

of these ideas (and even specific gags) into what would become Peanuts.

But it's also not

the end: there is one more book in the Fantagraphics series, the

inevitable odds & sods volume with advertising art and comic-book

strips and several of those small impulse-buy books from the '70s and

'80s that Schulz wrote and drew featuring his Peanuts characters.

So The Complete Peanuts, 1999 to 2000 is the end of Peanuts. And it's the pre-beginning of Peanuts. But it's not the end of The Complete Peanuts.

Since

we're talking about a fifty-year run by one man on one strip, and a

publishing project that spanned more than ten years itself, perhaps some

context would be useful. Luckily, I've been writing about these books

for some time, so have a vast number of links back to my prior posts on

the books covering years 1957-1958, 1959-1960, 1961-1962, 1963-1964, 1965-1966, 1967-1968, 1969-1970, 1971-1972, 1973-1974, 1975-1976, 1977-1978, 1979-1980, 1981-1982, 1983-1984, 1985-1986, 1987-1988, 1989-1990, 1991-1992, 1993-1994, the flashback to 1950-1952, and then back to the future with 1995-1996 and 1997-1998.

By this point in his career, Schulz was an old pro, adept at turning out funny gags and new twists on stock situations on a daily basis. But maybe his age had been catching up to him: there's a wistfulness to some of the gags from the last few years of the strip, and something of a return to the deep underlying sadness of the late '60s and early '70s. But Peanuts was always a strip about failure and small moments of disappointment, and that kept flourishing until the end.

And, if his line had gotten a bit shaky in the last decade of Peanuts, it was still expressive and precise. And there's no sign of his illness until in the the very last minute: the third-to-last daily strip, 12/31/99, suddenly has a different lettering style in its final panel -- maybe typeset based on Schulz's hand-lettering, maybe done by someone else in his studio to match his work. Then the 1/1/00 strip is one large, slightly shakier panel with that different lettering. And 1/2/00 is the typeset farewell: Schulz, as far as we can see in public, realized he couldn't keep going at the level he expected of himself, and immediately quit. There was no decline. (The last few Sunday strips, which came out in January and February of 2000 but were drawn earlier, don't show any change at all until that final typeset valedictory -- the same one as the daily strip to this slightly different audience.)

In the book, that loops right back around to the earliest Li'l Folks, which had typeset captions. And then we can watch Schulz take over his own lettering and get better at it over the three years of that weekly strip, hitting the level he maintained for fifty years of Peanuts after not very long at all.

We can also see Schulz's art getting crisper and less fussy as Li'l Folks goes on, as he turned into the cartoonist who would burst forth with Peanuts in the fall of 1950. Li'l Folks is minor, mostly -- cute gags about kids and their dog, mimicking adults or pantomiming jokes based on their shortness -- but there are flashes of what would be Peanuts later. And I mean "flashes" specifically: Schulz re-used many of the better ideas from Li'l Folks for Peanuts, so a lot of the older strip will be vaguely familiar to readers who know the early Peanuts well.

Perhaps most importantly, putting Li'l Folks at the end keeps this 1999-2000 volume from being depressing. It's already shorter than the others, inevitably, but putting the old strip back turns the series into an Ouroboros, as if Schulz was immediately reincarnated as his younger self, with all of his triumphs ahead of him (and heartaches, too -- we can never forget those, with Schulz and Peanuts).

Peanuts was a great strip, one of the true American originals. And it ended as well as any work by one creator ever could, having grown and thrived in an era where Schulz could have control of his work. (If he'd covered the first half of his century, that probably wouldn't have happened: Peanuts is the great strip that ended partly out of historical happenstance and partly because Schulz and his family wanted it so.) So there is sadness here, but there's a lot of sadness in Peanuts anyway: it's entirely appropriate.

A Weblog by One Humble Bookman on Topics of Interest to Discerning Readers, Including (Though Not Limited To) Science Fiction, Books, Random Thoughts, Fanciful Family Anecdotes, Publishing, Science Fiction, The Mating Habits of Extinct Waterfowl, The Secret Arts of Marketing, Other Books, Various Attempts at Humor, The Wonders of New Jersey, the Tedious Minutiae of a Boring Life, Science Fiction, No Accounting (For Taste), And Other Weighty Matters.

Networks and Contacts

Who Is This Hornswoggler?

- Andrew Wheeler

- Andrew Wheeler was Senior Editor of the Science Fiction Book Club and then moved into marketing. He currently works for Thomson Reuters as Manager, Content Marketing, focused on SaaS products to legal professionals. He was a judge for the 2005 World Fantasy Awards and the 2008 Eisner Awards. He also reviewed a book a day multiple times. He lives with The Wife and two mostly tame children (Thing One, born 1998; and Thing Two, born 2000) in suburban New Jersey. He has been known to drive a minivan, and nearly all of his writings are best read in a tone of bemused sarcasm. Antick Musings’s manifesto is here. All opinions expressed here are entirely those of Andrew Wheeler, and no one else. There are many Andrew Wheelers in the world; this may not be the one you expect.

The Latest Editorial Explanations

Previously on Antick Musings...

-

▼

2017

(218)

-

▼

July

(24)

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 7/29

- Incoming Books: July 26

- How The Hell Did This Happen? by P.J. O'Rourke

- Quote of the Week

- Bad Machinery, Vol. 7: The Case of the Forked Road...

- Thinking in Pictures by Temple Grandin

- The Complete Peanuts, Vol. 26 by Charles M. Schulz

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 7/22

- Lost and Found: 1969-2003 by Bill Griffith

- The Summit of the Gods, Vol. 1 by Yumemakura Baku ...

- Hawkeye, Vol. 3: L.A. Woman by Fraction, Wu, Pulid...

- My Favorite Thing Is Monsters by Emil Ferris

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 7/15

- Princess Decomposia and Count Spatula by Andi Watson

- UIniversal Harvester by John Darnielle

- Sweaterweather and Other Short Stories by Sara Varon

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 7/8

- Incoming Books: July 5 and 8

- Troop 142 by Mike Dawson

- The Complete Peanuts, 1999 to 2000 by Charles M. S...

- Pulse by Julian Barnes

- Great Plains by Ian Frazier

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of July 1

- Read in June

-

▼

July

(24)

My Life As a Twit

Hornswogglets

Recurring Motifs

- 246 Different Kinds of Cheese (121)

- A Series of Tubes (50)

- Abandoned Books (8)

- Adaptations (6)

- All Knowledge Is Found In Fandom (15)

- All of This and Nothing (11)

- Alternate History (8)

- Amazon Pimpage (80)

- America Fuck Yeah (3)

- Art Books (32)

- Awards (227)

- Backwards Glances (1)

- Belated Review Files (41)

- Better Things (53)

- Blog in Exile (78)

- Blogging About Blogging (263)

- Book Marketing 101 (5)

- Book-A-Day (1319)

- Books Do Furnish a Room (9)

- Books Read (259)

- Brain and Brain What Is Brain (2)

- Burned Book Contest (5)

- Candy (1)

- Captain Underpants (7)

- CauseWired (1)

- Circles of Hell (3)

- Class War Follies (6)

- ComicMix (222)

- Comics (2445)

- Confuse-o-vision (5)

- Conventions (59)

- Corrections (6)

- Crazy People (10)

- Critics and Their Criticism (2)

- Crowds and Their Funding (1)

- Deep Dark Secrets (13)

- Deep Thoughts (287)

- Don't Talk to Me About Love (2)

- Dungeon Fortnight (20)

- Editorial Explanations (13)

- Eisners (14)

- Exceptional Writers (2)

- Famous (5)

- Fan Fiction (8)

- Fanciful Family Anecdotes (41)

- Fandom (11)

- Fantasy (713)

- Favorites of the Year (32)

- Flame Bait (3)

- Food Porn (10)

- Foreigners Sure Are Foreign (323)

- Free Stuff (18)

- Gadgets and Gewgaws (13)

- Grammar (4)

- Great Mass Movements of Our Time (12)

- Great SF Novels of 1990s (4)

- Hard Case (8)

- High Finance (29)

- Holidays (90)

- Hornswoggler's Estleman Loren Project (15)

- Horrible Images That Will Never Leave Your Brain (12)

- Horror (87)

- House Rules (2)

- Hugo Thoughts (16)

- Humor: Analysis Of (292)

- Humor: Attempts At (61)

- I Love (And Rockets) Mondays (33)

- I Never Metafiction I Didn't Like (7)

- In Memoriam (23)

- Incoming Books (248)

- Inexplicable Occurences (8)

- Infographics (3)

- Interviews (12)

- It Must Be Mine (7)

- It's Only The End of the World Again (1)

- It's the Economy Stupid (51)

- Itzkoff (37)

- J'Accuse (2)

- James Bond Daily (59)

- Kids Today (1)

- Lego (11)

- Lies Damned Lies & Statistics (1)

- Linkage (873)

- Literature (193)

- Live Theater (8)

- Lurking Under Bridges (3)

- Magazines (8)

- Maps and Territories (1)

- Matters of Commerce (103)

- Measurements (1)

- Meme-o-riffic (212)

- Memoirs (85)

- Movie Log (352)

- Music (270)

- Mystery (186)

- Nature Red in Tooth and Claw (2)

- Navel-Gazing (1)

- Networks of Socialists (1)

- New York Times (20)

- No Context For You (3)

- Non-Fiction (468)

- Notable Quotables (107)

- Numbers Wonkery (10)

- O Canada (16)

- Obscure (5)

- Old Posts Resurrected (82)

- One of Us One of Us (5)

- Pedantry (4)

- Podcasts (4)

- Poetry (18)

- Politics (45)

- Polls (3)

- Portions for Foxes (54)

- Quizzes (1)

- Quora (1)

- Quote of the Week (835)

- Rants (111)

- Reading Into the Past (100)

- Reading Neepery (22)

- Reading Projects (1)

- Realms of Fantasy (3)

- Reportage (26)

- Reviewing the Mail (783)

- Reviews (3243)

- Rising Suns (23)

- Romance (8)

- Royalty (1)

- Saturday Is Bond Day (18)

- Scandals (4)

- Schadenfreude (4)

- Science Fiction (657)

- Secret Arts of Marketing (52)

- Self-Indulgence (1)

- SFF Art (30)

- SFWA (8)

- Short Fiction (43)

- Skeletons in the Attic (1)

- Skiffy (1)

- Smouldering Masses of Stupidity (40)

- Smutty (84)

- Snap Snap Wink Wink Grin Grin (5)

- Snark (16)

- Spam (6)

- Splendors of Publishing (351)

- sports (4)

- Starktober (33)

- Such A Deal I Have For You (6)

- Techno-Wonkery (13)

- Tedious Minutiae of a Boring Life (352)

- That Old-Time Religion (6)

- The Criminal Mind (4)

- The First Thing We Do Let's Kill All the Lawyers (6)

- The Great Idiot Box (7)

- The Horrors of Geography (1)

- The Joys of Bookselling (73)

- The Making of Lists (33)

- The Past Is a Foreign Country (280)

- The War Between Men and Women (29)

- The Working Life (11)

- there (1)

- There Will Always Be an England (74)

- This Year (53)

- Those Crazy College Kids (4)

- Thrilling Tales of Science (15)

- Tie-Ins (1)

- Towering Stacks of Unread Books (14)

- Travel Broadens The Mind Until You Can't Get Your Head Out the Door (100)

- True Names (3)

- Twelve Days of Commerce (17)

- Universal Laws (2)

- Video Killed the Radio Star (3)

- Vintage Contemporaries (19)

- Western (4)

- WFA Judgery (57)

- What These People Need Is a Honky (1)

- Wide World of Wheelers (9)

- Widgets (2)

- Wonders of New Jersey (42)

- Words Words Words (30)

- Years of Unremitting Toil (2)

- Years Prematurely Declared to Be Over (3)

- You Know: For Kids (307)

No comments:

Post a Comment