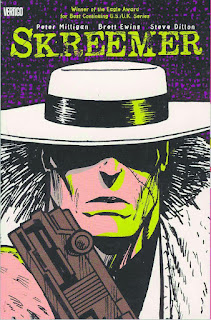

Skreemer is a SFnal gangster story, originally serialized in six comics issues in 1989 and collected some time later. It was written by Peter Milligan, with art by Brett Ewins and Steve Dillon. It's set after a slow apocalypse: a series of plagues seems to have just overwhelmed the world and collapsed governments. At least, it's done that in the unnamed city the book takes place in, and, as far as the narrative says, across all of America.

Because it's a gangster story, most of the main characters are gangsters: Veto Skreemer is the main character, the guy on the cover. His henchmen and allies and enemies are most of the others; a family named Finnegan are the contrasting group of civilians.

For the resonance, for the kind of story Milligan wants to tell, they have to be gangsters. Outlaws. Violent men carving up empires of illegal activities. And they are.

But there's no society for them to be outlaws against. They are as much government as their nation has, though Milligan doesn't spend time showing that: for his story, they have to focus on drugs and prostitution, not taxes and resolving disputes. But if the reader thinks about it for a moment, it's clear that their world can't have any functioning money, and doesn't have any laws left for them to break.

They're actually warlords, not gangsters. Milligan clearly knows this: the fact that the gang leaders take the title of President and carve up the nation shows he's gesturing in that direction. There's dialogue that talks about the whole nation, but all we see is this crumbling ruin of a city.

Who is picking up the garbage? Who is trucking food into the city? For that matter, who is growing food, and do the Presidents have guards stationed on the farms to make sure the food flows into the otherwise-starving cities? How is this society functioning at all, if the only order is imposed by '30s-style gangsters who spend all their time lounging in sybaritic splendor and baroquely murdering each other?

None of that is what Skreemer is about. The reader is not supposed to think about any of that; the world-building is besides the point. This is a story about people, in horrible, extreme situations; the world is constructed around them to force those situations. Some readers may find that artificial and limiting; Skreemer is not a good book for those readers.

That's what's missing in Skreemer: I don't want to say what's "wrong" with it, since it's not part of the plan or the story to begin with. It's an aspect of the book and story and world that simply doesn't exist, is not taken account of.

The story of Skreemer is about predestination and choices, about the evil that men do and the good they claim they could possibly do. Veto is cold and calculating in every moment, from the time we see him as a boy of about nine. If we're SF readers, we realize early he has some kind of presentiment of his future, but we don't get the full explanation until nearly the end. But the short version is: Veto knows what will happen. All of it, all of the important moments. Everything has already happened, is already done, as far as he's concerned. We don't follow his point of view - we see him entirely from outside, usually as a cipher - but he's another one of those precognitives who are utterly trapped, who feel like they are acting out exactly what they must do, without choice or change or free will.

Milligan tells Veto's story sideways and inside out, seeming to jump around the timeline while actually laying it all out very carefully and methodically. Our narrator is not even born during the course of the story; we never see him. Nothing is a surprise to Veto, even as he tries to find a way out of his destiny: he thinks if he can have a child, that will break the pattern he's seen. (He's right, I suppose.)

It's all juxtaposed with the story of the Finnegan family, who are just trying to survive the chaos, though not all of them do. The father is obsessed with the old drinking song "Finnegan's Wake," maybe just for last-name reasons. They go through their own horrible situations, and choices.

Well, if they are choices. Veto doesn't think so: he thinks it's all set, all final already. Everything from the collapse to his rise to his own inevitable death: utterly unalterable.

That's the story of Skreemer. The things Veto Skreemer saw and lived through, mostly in that order. It's dark and full of violence, with horrible things happening to characters we care about. It's a gangster story: that's required. Blood must flow, betrayals must be swift and shocking, and most of the cast must not make it to the end.

It's a very good SFnal gangster story: stronger in the gangster than the SF, inevitably. Ewins and Dillon tell it in a straightforward adventure-comics style of the era, without fancy panel layouts, to support Milligan's complex flashbacks-within-flashbacks structure. That was a good choice: a more baroque visual style would have been too much baroqueness at once.

It's not quite a lost classic, but it's a strong story by three creators who have worked together in different permutations a number of times, and have later done other things that this story prefigured. It's a solid comics story that does some interesting things: there's always room for more like that.

No comments:

Post a Comment