Some people end up in those jobs their whole lives, of course. Some people don't have a road to begin with. But let's assume you had a road and were going to follow it at some point.

That's the student job, the summer job, the first job - the thing you do because you want or need to make some income and it's available. I was a cashier and then a supervisor of cashiers at a Bradlees discount store, way back in highschool; in college, I worked on the student security force, Campus Patrol.

Guy Delisle worked in a paper mill for three summers.

Blue-collar jobs, especially in big factories, are just more interesting as jobs - especially to people of the sitting-in-offices-and-looking-at-computer-screens classes - than the other things young people fall into, foodservice or retail or pet grooming or other random minor services and goods. So Delisle had something inherently compelling: the budding art-school student, his head full of comics and drawing, working twelve-hour shifts amid massive, dangerous, loud machinery with a whole bunch of men with completely different ideas and plans and lives.

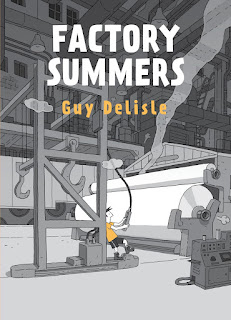

It took Delisle almost forty years to tell that story, but he did: it's Factory Summers. At the age of sixteen, in the early '80s, he was hired as a "sixth hand" at what was then the Reed plant at the mouth of the Saint-Charles river in Quebec City. The plant was loud and hot and steamy, and the work was long and tedious, the kind of physical work that's easy to know what to do but that takes a while to get good at the little subtleties of doing it well. Giant rolls of paper need to be hoisted by machine, without swinging or falling, and put into position quickly and efficiently. Waste paper needs to be shoved down into the beater underneath with a big wooden pusher. Debris needs to be cleaned with high-pressure hoses, over and over and over again. Rolls need to be trimmed and cleaned and cleared. All the while giant machines are running at high speed on all sides: it was a modern, First World factory with serious safety precautions, but big machines are inherently dangerous, and the people who work around them learn that very quickly. And they have stories about the ways those machines can kill people - stories always told as "there was this guy who fell from up there" or "one time someone got caught in that" without names, so the new guy is never quite sure if those are true stories or legends.

Delisle tells this story straightforwardly, starting with his interview for the job and running through three main sections, each corresponding to one summer, plus a short coda at the end, showing what he ended up doing instead during what could have been the fourth summer. Again, the paper mill was not his road: he wanted to become an animator, and he did.

There are co-workers that reappear, but mostly within one summer: people change and move on, so the crew one year is different from the one before. Or, at least, the interesting people that Delisle wanted to focus on were different: the long-timers, working at the mill as a career and waiting for retirement, were there all along. He doesn't know what happened to some of them, and he's telling this story forty years later, so some of them don't have names. (Maybe some read the book and recognized themselves!)

Well, there is one person who is important but only appears a few times: Delisle's father was an engineer at that plant, working upstairs in the offices. Delisle saw him only rarely, and the two weren't close: the parents had gotten divorced a few years before and the father, as Delisle depicts him, was a solitary man who talked incessantly whenever in company. This is not a book about Guy Delisle's relationship with his father - but that's a strand of the story.

Delisle draws himself in a modern iteration of ligne claire - precise lines of a a medium width, simplified features. He also uses the yellow workshirt he wore as a pop of color on the otherwise black-and-white-and-gray pages, as seen on the cover. (Noises, smoke, and a few other things are also in the same yellow.) But his coworkers are drawn in a somewhat more realistic style, more like the machines and surroundings: not full realism, but with more detail to features, more blemishes, more shading. It makes the young Delisle central to every panel he appears in, and cements him as our viewpoint; it underscores how he was different in this environment, a visitor rather than a resident.

Delisle doesn't aim for big revelations or lessons in Factory Summers. It was an interesting time in his life, and the intersection with his father's life gives it added resonance: but he doesn't stretch any of that, he presents it as it was, or as he remembers it now. This is the story of a just job, what Delisle did before he started doing what he really wanted to do.

1 comment:

He is the French Canadian author illustrator and cartoonist who created Extreme Journey & other stories became a traveller & adventurer staunchly left-wing anti-war pacifistic & neutral to former enemies like North Korea Egypt Israel Iran Iraq Syria Lebanon Western Sahara Angola Mozambique Cape Verde Ghana Gabon Somalia South Africa & other non-aligned nations of the world.

Post a Comment