I keep checking the cover to make sure that "A" is capitalized, which means, I think, I'm exactly the kind of person this book is for: bookish, detail-oriented, interested in quirky bits of history, borderline obsessive.

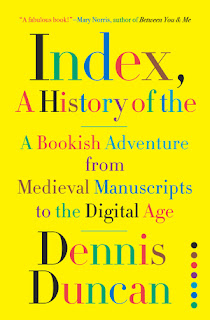

Yes, this is a history of the index, that thing at the back of the book that tells you where you (assuming you are famous) are mentioned, so you don't have to read the book itself. Indexes - by the way, Duncan prefers that to "indices," but I tend to go the other direction, only because I always prefer the most baroque option; ask me about "octopodes" some day - are useful and, like a lot of things in this world, more complicated and messy than non-experts think.

Now you are thinking "Oh! Is this yet another 'how this one thing changed the entire world' book?" Well, yes, sort-of. Duncan is not claiming the entire edifice of the modern world is based on the work of Robert Grosseteste and Hugh of St. Cher [1], but, in the way of that strain of best-selling non-fiction, he is going to trace different kinds of indexes, mostly but not entirely the usual kind printed in physical books, from as far back in time as is feasible right up to Google, which does use the term "index" quite a lot when talking about what its big fancy search engine does.

The point of an entertaining and informative non-fiction book - one that is either or both of those things, I mean, though it's obviously better if it's both at once, as this one is - is to tell the reader things she doesn't already know, preferably things that are worth knowing. (There is an entire vast world of academic publishing, full of books that could tell you things you don't know that you would never ever care about for a second.) Duncan succeeds on both counts here: I wasn't really clear in my own head on the difference between a concordance and a subject index before I read Index, and now I could possibly explain them, as long as someone asks me within the next two or three days and I'm not distracted.

(But! I could also look up, in Index's index, "concordances, births of the index" and refresh my memory on pages 51-52 and 55. In fact, I just did that, since I figured a book on the index should be particularly accessible through its own index. And so it is: Index has an extensive, detailed index of its own, compiled by professional indexer Paula Clarke Bain. It also has extensive endnotes, a list of illustrations, and, as something of a bad example, a partial computer-generated index of this book. As usual, Norton rules the scholarly-apparatus-for-lay-readers world.)

In short: Index is much more entertaining than you would think, full of quirky literary stories from the past seven centuries or so, all told well and aligned to the central thread of Duncan's thesis. It's long enough to tell its story and short enough not to wear out its welcome. If you are a bookish person, you probably will want to read it: it could very easily be this year's Eats, Shoots & Leaves.

[1] No, not that Cher. That would be silly. And only dead people can be canonized anyway.

No comments:

Post a Comment