I'm hip-deep in reading for the Eisner Awards, and if I try to give every one of these books its own post, none of those posts will ever get finished. So this, instead, will run (quickly, I hope) through a stack of books published for kids and teens during 2008.

I'm hip-deep in reading for the Eisner Awards, and if I try to give every one of these books its own post, none of those posts will ever get finished. So this, instead, will run (quickly, I hope) through a stack of books published for kids and teens during 2008.I'm neither a kid nor a teen, though, so -- even if you're not, either -- you might find some of these book of interest, as I did.

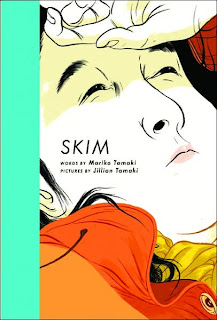

Skim

This is a lovely -- both in the delicate and detailed drawings of Jillian Tamaki and in the thoughtful and incisive writing or Mariko Tamaki -- book, told in the voice of teenager Kimberly (Skim) Keiko Cameron. Skim is chubbier than she might prefer, an aspiring Wiccan, a student at a private girls' school, and (like so many teenagers) not at all sure of where she'll fit into the world. It's the sort of story we've all seen a million times, especially in YA fiction: a sensitive young person tells her own story -- in this case, there's even specific references to writing this in a diary -- but that's because millions of us were sensitive teens, and it's a story that can resonate strongly when told well.

And this is told very well; it's one of the finest graphic novels I've read recently. The Tamakis make Skim a real, specific person; she's grumpy and distracted, wondering about love and Wicca and friends and the whole world. There are some "issues" in this book, but I'm not going to tell you what they are; merely mentioning them would give the wrong impression. Skim isn't a book about "problems facing today's teens" -- it's one young woman's story, told brilliantly and by turns funny and moving, sweet and sad. If you see a copy, pick it up: this is a real gem.

No Girls Allowed

No Girls AllowedThe stories of seven women who dressed as men for extended periods of time -- from the Egyptian Pharoah Hatshepsut to US Civil War soldier Sarah Rosetta Wakeman -- are told, in lots of stilted captions and slightly less stilted dialogue, enlivened by Dawson's clear, crisp, and slightly quirky art. (One example: all of the female characters -- down to the images of the creators on the back flap -- have that circle on one cheek that you can see on Mu Lan on the book cover to the left.)

No Girls Allowed is much more "educational," and much less fun. I'm sure it could be very useful to some kid staring down the barrel of an essay deadline, but the stories it tells are rendered dry and flattened. Hughes never speculates or goes beyond what history records, which makes this useful as a reference, but not as much fun as a collection of stories. All of these women were highly secretive -- they had to be, to pass as men for years -- and so there's often not a lot known about them...but that's all there is in No Girls Allowed.

Claire and the Bakery Thief

Claire and the Bakery ThiefA pre-teen girl moves to the small town of Bellevale when her parents buy an old bakery there, and at first has trouble making friends, until she meets fellow outdoors-lover Jet. But the parents are fighting -- Claire's mother didn't want to leave the big city in the first place -- and eventually Mom goes away with a mysterious Artificial Flavoring Salesman. Claire and Jet then need to find and save her.

This is positioned as the first in a series, and it means well. (There are even recipes at the end, and a message of eating local/organic/healthy.) But it's both trite and silly, and ends up either trivializing or ignoring Claire's parents' marital troubles. OK for young girls who like to cook, not of much interest to anyone else.

Johnny Boo: The Best Little Ghost In The World

Johnny Boo: The Best Little Ghost In The WorldKochalka has done books for kids -- or books that are also appropriate for kids, perhaps -- before, and his quick, cartoony style works well in this short story about a boy ghost and his best friend Squiggle (who looks different, and flies, but is also a ghost, I guess). Boo and Squiggle run and play, and then have some trouble with an ice cream monster. It's a fun, light adventure story for boys, with the loose narrative structure and ideas of a game a couple of kids would play on the spot out in the yard.

So this is light, but a lot of fun -- probably of most interest to younger boys (up to six or seven) and the more tomboyish girls of similar ages.

Yam: Bite-Size Chunks

Yam: Bite-Size ChunksYam is the little boy in the all-encompassing jumpsuit on the cover; his TV-dog doesn't seem to have a name. This book collects a twenty or so short wordless comics stories about him and his friends, ranging from single-pagers up to one thirty-eight pager. Several of the stories originally appeared in Nickelodeon Magazine, so this character is already familiar to a swath of the preschool set.

The stories are the kinds of things you'd expect from wordless stories for preschoolers -- lots of food and friendship and being nice, with some game-playing and mild conflict and (in the longest story) Yam being in love with a cute shopkeeper but eventually realizing he's just a kid and she isn't. Barba's art is cartoony, but more detailed and noodly than Kochalka's, with a lot of things to look at in every panel. My eight-year-old enjoyed reading it with me, but the subtle details of the stories -- they're wordless, remember -- sometimes escaped him, and will likely escape much of the target audience.

Korgi Book 2: The Cosmic Collector

Korgi Book 2: The Cosmic CollectorThis is another wordless story, but this time it's a fantasy tale, set among winged people called Mollies who live in Korgi Hollow with their fox-like Korgis. (The girl on the cover is a Mollie named Ivy, and the "dog" is her Korgi, Sprout, who has special powers.) The backstory is pretty extensive, for a story told without words, and that requires a several-paragraph long prologue up front (as narrated by a giant friendly toad with a hat and a telescope) as well as a list of characters and races at the end. (This does mean that the reader finds out the point of the story, and something of the details, only after the story is done, which is sub-optimal.)

There's this alien (we learn from the list of characters) named Black 7 (ditto) who shoots Mollies to steal their wings and tack them up on the walls of his house. Ivy takes exception to being treated that way, and goes to get her wing back, either by sneaking or by force. Korgi has more action than most of these other books, and so could skew slightly older -- though the wordlessness tends to push the age down. (As does the slightly twee names and aspects, from "Mollies" to the talking friendly toad Wart.)

Slade's art is gorgeously dynamic and detailed, with magnificent shading. I suspect the art is well more than half of the appeal of Korgi, though the story is just fine for what it is.

Coraline

CoralineI've now had my fill of Coraline for a while, having seen the film, re-read the Gaiman novel and now read this comics adaptation by Russell within barely two weeks. Russell's adaptation is much more faithful into the comics form than Henry Selick's was for the film, but the film is a much more impressive achievement -- even leaving aside the 3D and other aspects that give film an undeniable edge over any book.

Russell tells Gaiman's story, entirely using Gaiman's words as far as I could tell, and doesn't change even the slightest of plot details. Selick, though, changed quite a bit of the details, adding a character for Coraline to talk to, changing the nature of her final confrontation with the Other Father, and seriously changing the dynamics of the final well scene. Selick's changes all increased the tension and visual interest; Coraline, as a novel, was very quiet and centered in Coraline's head. That's the great gulf between a novel and a movie, of course: a movie can only show what's happening on the outside, though it can hint and imply mental states, while a novel can dive right into a stream of consciousness and make the reader know exactly why a character did something. Graphic novels, at their best, hybridize the two forms -- they can't be quite as visually exciting as movies, since they don't move, but they can come very close. And they can show the inner life of a character just as fully and in as much detail as a novel can.

But Russell, in adapting Coraline, didn't add anything to the mix but his own prodigious skills -- the story is precisely the same, and the otherworldly elements, such as the Other Mother and her creatures, are left understated, not going an inch beyond Gaiman's descriptions of them. His graphic novel is precisely Gaiman's Coraline translated faithfully, while Selick's movie is the same story given a new visual style and a few changes to work better in a different medium.

Unfortunately, to my eye, Russell -- though one of the masters of modern comics and the creator of a long shelf of great adaptations, from Elric to the massive, magisterial Ring of the Nibelung -- wasn't the best choice to illustrate this particular story. The original illustrations for the novel (at least in the US editions I've seen) was Dave McKean, who brought his usual chiaroscuro forms, which imply much more than they illustrate. And Selick's movie also took a more surreal visual style, with its lanky puppets and gorgeous but subtly unreal settings. Russell, on the other hand, is magnificent at drawing real things and real space -- his Coraline is a particular girl of about ten, and the Other Mother looks like a real woman with buttons for eyes.

That's usually a great strength, but it hampers Russell, particularly near the end, when the Other Mother's world is supposed to simplify down and become more crude -- "no more than a crude scribble" and "just a child's scrawl." Russell draws those scenes as warping and twisting, but not deteriorating -- not at all like the drawings of a child. The one place where the text gives specific visual instructions that are precisely translatable to comics, Russell is too good an artist to carry them out.

It may be just that I've had my fill of this story right now, but I found Russell's comics version the third and least of the versions of Coraline. It's neither the pure words Gaiman wrote the story in nor something new and wondrous like Selick's movie -- it's gorgeous and impeccably drawn and laid out, as always with Russell, but doesn't quite grab a life of its own.

No comments:

Post a Comment