Because I don't want to give all of these things their own entries -- partially because I still have hopes of keeping the length of the review of each of them down to something reasonable -- I'm shoving them together into one post, which will go up once I've read a whole bunch of comics, or the post has gotten too long, whichever comes first.

Because I don't want to give all of these things their own entries -- partially because I still have hopes of keeping the length of the review of each of them down to something reasonable -- I'm shoving them together into one post, which will go up once I've read a whole bunch of comics, or the post has gotten too long, whichever comes first.These will probably all be books that I got from the local libraries, as I ransack their somewhat hodge-podge graphic novel selections. (Example: in the entire system, they have Spirit Archives Vol. 17, but no others.)

Plastic Man, Vol. 2: Rubber Bandits by Kyle Baker (DC Comics, 2005, $14.99)

This collects the second clump of stories from Baker's well-regarded but short-lived Plastic Man series of 2004-2006 (20 issues, as far as I can tell). I looked at the first volume in late 2007, and wanted to like it better than I did.

And my reaction to this book is pretty similar. I laughed a lot while reading it, but I still wish Baker's panels at this point in his career weren't so blocky and so utterly separated from each other; it looks like he draws each panel individually and then sticks them together on the page. This is funny stuff, but it still looks a lot more like storyboards than comics, and that tends to damp the energy of his panel transitions. This Plastic Man is supposed to be manic and high-energy, but the discrete square panels and floating captions leech a lot of that energy out. Oh, it's definitely funny, but it comes across as less funny and goofy than it should, as if we're seeing all of the hijinks through a frame.

Ojingogo by Matthew Forsythe (Drawn & Quarterly, September 2008, $14.95)

Ojingogo by Matthew Forsythe (Drawn & Quarterly, September 2008, $14.95)I glanced at this over the Eisner Judging Weekend, but didn't get to read it then -- one of the other judges noticed that it was nominated as a webcomic in 2004 and then again in 2006, and the consensus of the judges was that we didn't want to just keep giving nominations to the exact same things every two years.

It's a pantomime comic -- well, there are tiny bits of possible dialogue that I suspect is in Korean, but that's very minor -- set in a surreal world among lots of very strange-looking creatures. The girl and squid on the cover are the central characters, though they're not precisely friends. No one seems to be all that friendly anyone else here, and everybody changes sizes at the drop of a hat, too.

It's too bad that Warren Ellis used up the sentence "this is one odd fucking book" on Skyscrapers of the Midwest; that's certainly somewhat odd, but Ojingogo races around the odd track five times while Skyscrapers is still putting its shoes on, and then runs up the side of the judging stand for a victory lap. This thing is pretty near indescribable; I can't even begin to characterize the entities in the story. It's worth looking at, and the cartooning is great, but I don't really know what to think of it.

One! Hundred! Demons! by Lynda Barry (Sasquatch Books, 2002, $24.95)

One! Hundred! Demons! by Lynda Barry (Sasquatch Books, 2002, $24.95)After literally years of claiming that I didn't like Barry's work -- which I'd mostly seen as that alt-weekly strip with Marlys in it, which set my teeth on edge every single time I looked at it -- her introduction to The Best American Comics: 2008 and then the magnificent autobio/writing manual What It Is came as a huge surprise. But I'm big enough to change my mind, and I decided to look for more by Barry (but still avoid that Marlys creature if at all possible).

This is, I think, her book just prior to What It Is, a series of loosely-themed shorter strips that originally appeared on Salon -- in fact, a quick check shows me that they're still there -- in 2000. The book gives the strips a little more context, adding an introduction and collage-style title pages for each story (in the style that blossomed into the much more collage-heavy What It Is).

Barry was inspired by an old Zen painting exercise called One Hundred Demons, though I think the original exercise was just to paint the demons, not to tell stories about them. Barry's demons -- there are actually seventeen of them here -- are stories about things she regrets or can't forget, semi-fictionalized bits of her life. The book One Hundred Demons reprints each typical four-panel Barry page as two panels on each of two facing pages, making them larger and more inviting. (One of the things that annoyed me about Barry's work in the alt-weeklies was how many words she crammed into a tiny space -- reprinting the strips at a larger size keeps all of the words, but allows more space around them.) As in What It Is, Barry mines her own past for moments of universal relevance.

One! Hundred! Demons! isn't as all-encompassing and self-assured as What It Is, but the stories are engrossing and the cartooning is engaging. Barry is much more fun than I used to think she was.

Batman and the Mad Monk: Dark Moon Rising by Matt Wagner (DC Comics, 2006, $14.99)

Batman and the Mad Monk: Dark Moon Rising by Matt Wagner (DC Comics, 2006, $14.99)It may be possible to pinpoint the moment when I decided that long-underwear comics just weren't worth it for me anymore, even if I was following a creator hither and yon across the fields of comics. (I apologize for that metaphor, but I'm feeling puckish tonight.)

I bought Matt Wagner's stylish Batman and the Monster Men -- yet another Batman-early-in-his-career story, beloved by all who want to avoid the morass of contemporary continuity and pretend that they're Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli -- in 2006, but when this book was published, nine or twelve months later, I picked it up at my comics shop, heaved a sigh, and put it back.

But I've now read it, through the magic of the public library, and it's a very serviceable Matt Wagner entertainment, with appropriately moody coloring from Dave Stewart and a whole lot of Wagner drawings of Batman grimacing as he gets stabbed or sliced by things. It's the loose sequel to Monster Men, and Wagner appears ready to create Batman mini-series as needed for as long as he and DC are interested. And this is quite good for a Batman story, but it's still a Batman story -- derivative and attenuated, with most of its essential strength derived from the audience's long knowledge of these characters. Wagner's capable of much better than this, but I imagine that Batman is a more consistent way of paying the bills, so I don't begrudge him the work. But I will continue to save my money, almost all of the time, for cartoonists doing their own stories.

Tom Strong, Book 1: written by Alan Moore; art by Chris Sprouse and Alan Gordon with segments by a whole bunch of other people (America's Best Comics/Wildstorm/bought by DC and all of Alan's magic couldn't stop it; 2000; $17.95)

Tom Strong, Book 1: written by Alan Moore; art by Chris Sprouse and Alan Gordon with segments by a whole bunch of other people (America's Best Comics/Wildstorm/bought by DC and all of Alan's magic couldn't stop it; 2000; $17.95)I'm not particularly well-read in Moore's return to superheroes of the late '90s; I've picked up Supreme but never read more than a few pages, and I was frankly bored with Promethea. It always looked like a retreat to me: I have no problem with Moore doing whatever work most interests him now -- and I'm even willing to accept that this is what most interested him in 1999 -- but a definite lack of ambition was visible from miles away.

But people have generally said good things about Tom Strong, so, when I had a chance to finally take a look at his adventures, I took it.

And it turns out I was right: this is pleasant, but very minor, and there isn't much ambition to it. Moore is writing modern Doc Savage stories about a big guy who's a great role model and always does the right thing. The result are perfectly acceptable adventure stories, with very slick, professional art from Sprouse and Gordon, but the format -- having a required flashback (or, in one case, a flashforward) in the middle of each issue -- gets a bit tedious, as does the relentlessly sunny tone of the villain-punching. The backstory isn't particularly interesting or complicated; Strong married his childhood sweetheart and had one daughter (who seems to still be a teenager in 1999, even though she might be seventy years old), and everybody is very friendly and happy.

Tom and his family never seem to be in much danger; they're always much more than a match for any threats that they confront. That makes for happy endings, but not for a whole lot of tension. Tom Strong is a kinder, gentler Alan Moore, and I found it awfully thin soup.

Will Eisner's The Spirit Archives, Vol. 17: ostensibly entirely by Will Eisner, though he had plenty of assistants whose individual contributions can no longer be traced (DC Comics, 2005, $49.99)

Will Eisner's The Spirit Archives, Vol. 17: ostensibly entirely by Will Eisner, though he had plenty of assistants whose individual contributions can no longer be traced (DC Comics, 2005, $49.99)I've spent the last few years catching up on Eisner, whom I hadn't read much before that -- I've looked at The Best of the Spirit, Life, in Pictures, A Contract With God and related books, The Plot, and Will Eisner's New York. I think I've got a good handle on his modern graphic novel career, which has some real strengths (besides the mere fact that he was a pioneer at nearly everything he did) as well as some very glaring weaknesses. But I've read less widely in his Spirit stories, so I'm trying to look at those whenever I have a chance.

This volume is the single one that any of the libraries in my home county has; it seems a very odd and arbitrary choice, but at least this book -- collecting the weekly seven-page stories from July through December of 1948 -- is from what I understand to be the best period of the strip.

The things that annoy me in Eisner's later work show up in this phase of his career quite differently: the dialogue is much less ethnic (as are all of the characters), but his distinctive, and off-putting, way of E-M-P-H-A-S-I-Z-I-N-G words was just as intrusive in 1948 as it was forty years later. (I always want to read those words with dashes in them as if the speaker was spelling them out -- and I very much doubt that was Eisner's intention.) He had a quite different cast of stereotypes in the '40s: not the soap-opera pre-war Jews of his later work, but a Central Casting conglomeration of vaguely Mediterranean gangsters, a comic-relief black boy, upright Irish cops, and the obligatory "non-ethnic" WASPs at the center.

But his strengths were all fully formed in 1948 as well: a great sense of page layout and design (second to no one in the world at that time, and hugely influential even now); wonderfully expressive cartooning, particularly of figures in motion; and a masterful way with story, allowing him to shift from pure farce to near-tragedy in subsequent stories with the same characters. The Spirit stories are very much genre tales -- they're mostly crime-fighting stories only a step or two removed from superheroes, with some side trips into supernatural, sentimental, and even Western stories -- but they're all, at this point, exceptionally well-told stories, by a creator (and his uncredited staff) at the height of his energies.

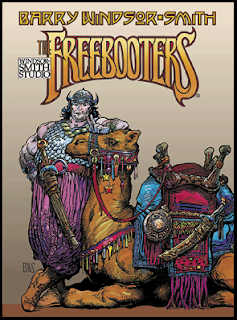

The Freebooters Collection by Barry Windsor-Smith (Fantagraphics, 2005, $34.95)

The Freebooters Collection by Barry Windsor-Smith (Fantagraphics, 2005, $34.95)According to the cover, this is The Freebooters, or perhaps Windsor-Smith Studio: The Freebooters. There's a half-title page (though no title page, per se) that says Barry Windsor-Smith: Storyteller: 2005. But the copyright page says twice that it's The Freebooters Collection, so I'm going with that. The rest of the book has a bit of that air of uncertainty, as well -- when the reader comes to the end, he realizes that this isn't actually a complete story. For thirty-five dollars, what the reader gets is all of the "Freebooters" material that appeared in the nine issues of Barry Windsor-Smith: Storyteller of 1996-97, plus a twenty-seven page aborted beginning of the story from a few years earlier, plus another forty-eight pages of pieces of continuation of the main story (including various sidebars and diversions), plus notes on the story in a definite voice (which is neither Windsor-Smith himself nor otherwise specified), plus a reprint of an article about the storyline from the magazine Hogan's Alley. That adds up to nearly two hundred pages of art and story -- gorgeous, intricate Windsor-Smith art and engrossing story -- and other materials, but nothing at all like an ending and not even all that much middle; this is still all beginning and scene-setting.

So The Freebooters Collection is a monument, or perhaps a tombstone, for a dead story. There's no reason to think that we'll ever know what happens to any of these people; Windsor-Smith had intended that this story would run for several years (in tandem with the other two stories in Storyteller), but that didn't happen and never will. Maybe Windsor-Smith will get a chance to go back to this story eventually, but there's been no sign of that so far, and it's been over ten years. (This book, despite being published in 2005, doesn't seem to have any material from later than the original 96-97 run of Storyteller.)

I can't say much about the actual story of Freebooters; it was still gearing up when Storyteller shut down. (Storyteller's model -- three stories in one magazine-format monthly publication, with each story rotating between five-to-seven-page "backup" stories and a twenty-some-page "lead" story -- didn't help here, since every new installment had a different page count and thus was limited as to how much it could move the story forward.) The characters are interesting, and the plot is just getting started when the story cuts out. Perhaps that was part of the problem -- if, nine months into a series, a story is still setting up the situation, that's too slow for a lot of readers.

The other interesting aspect of Freebooters is Windsor-Smith's anger and bile at Dark Horse Comics, the original publisher of Storyteller -- he

still firmly believes that it was the almost total lack of advertising and marketing support from its original publisher (hereafter referred to as OP) that kept it completely invisible to an entire demographic of an adult market that had quit reading comics years before.Yes, Windsor-Smith is mad that Dark Horse -- during the middle of the longest sustained downturn in the modern comics industry, when half of the comics shops went out of business, several publishers went under, and Marvel went bankrupt -- didn't spend unprecedented amounts of money to advertise it to people who don't read comics.

And what would it have attracted them to? A large-format, relatively expensive monthly periodical, sold in stores that those potential customers don't patronize, telling three entirely separate stories -- none of which were complete, or anything like it, in a single issue. Windsor-Smith is a wonderful storyteller, yes, but is thirty-two pages of three pieces of set-up going to be sufficient to convince a non-comic-reader to come back month after month? (Even assuming they can be convinced to come to a comics shop in the first place, which I'm very dubious about.)

Even now, ten years later, similar projects of much, much higher commercial potential -- like the Stephen King comics from Marvel -- can bring in an outside audience to comic shops once (for the debut issue), but sales drop quickly afterward. The audience for periodicial comics is entirely within the direct market; any creator who wants to reach beyond that needs to have a complete story to offer that potential "outside" audience.

So I think Windsor-Smith had very, very unrealistic aims for Storyteller, and that he chose the worst year possible to try to achieve them. If he'd picked one of the three stories, and told it straight through, he would have had a better chance. (But, even then, I expect that outside audience would only really have been interested once there was a single book, at a reasonable price -- this one doesn't qualify, since it's incomplete and not a reasonable price for that audience.) If he'd kept the book to a more typical size, he might have had better luck within the direct market -- and there was no serious chance of getting Storyteller distributed outside of that market, anyway.

It's a shame; I bought all of the issues of Storyteller -- and still have them, somewhere, though I had the same storage problems as everyone else -- and wanted to see it succeed. But, looking back at it, and with a lot more experience in publishing and marketing since then, I can't side with Windsor-Smith, as much as I'd like to. As far as I can see, Dark Horse made a heroic effort on behalf of a talented and demanding creator, and got absolutely no credit for it. (And probably lost a bundle as well.)

2 comments:

have you read Top 10? I thought it was by far the best of the ABC line (okay, Promethea was more ambitious, but...) I like Tom Strong, but it is very relaxed.

Interestingly, when I wanted to show someone The Spirit, I picked vol. 17 as the peak. If the library is only to have one volume, it's an excellent one to have!

Post a Comment