The description of Jodi Lafebre's graphic novel Always Never makes it sound like a late-in-life love story: mayor Ana and Zeno, who has been for decades almost equally a doctoral student in physics, a commercial sailor, and a bookstore owner, finally are in the same place at the same time in their sixties, possibly ready to finally give their relationship a chance. And that is where the story starts...in chapter twenty.

The following chapters are also the preceeding chapters, as Lafebre traces the story of their lives backwards, jumping a few days here, a decade there, to wind all the way back to the moment when they met. We get previews of their history as we go: Ana and Zeno, like everyone else, talk about their shared past.

But, also like everyone else, they can't talk about what hasn't happened yet. So what we see later in the book will color what we've already read that happens later in time, but the narrative will continue moving forward. Which is to say: backward.

It's not just a way of telling the story, though. Zeno has a theory about time, about the possibility of rewinding time, and his long-delayed doctoral dissertation is about exactly that. And that dissertation may have been accepted as the book opens, which means....he's right?

That possibility stands behind the entire story, and crystallizes the final moments here. This may be exactly what he theorized - but, if it is, that's outside of this story. If time rewinds and tells a different story, what happens then?

Ana and Zeno are mostly separate, those long years, trading letters - sometimes actually trading them, sometimes writing and discarding those letters, for themselves rather than for the other one - talking on the phone, thinking about each other, and mostly living their own lives. Ana married and had a daughter, who is grown with a child of her own by the beginning (or end) of the book. Zeno was engaged, in his telling, many, many times, but nothing more than that - how do you tie down a sailor?

There are other motifs besides the doctoral thesis, other pieces that recur. One of Ana's longest projects as mayor was building a bridge for her town, connecting what seem to be the neighborhoods on top of two very steep hills - and that project takes much longer, and goes through more changes, than anyone expected. But, of course, because of the way Lafebre tells the story, we see it completed first - because of the way he tells this story, we see the end of everything first.

That, almost paradoxically, makes Always Never a more positive, happy story. We already know how it will end; we know things will be just fine. What we don't know, or don't know enough about, is how it begins.

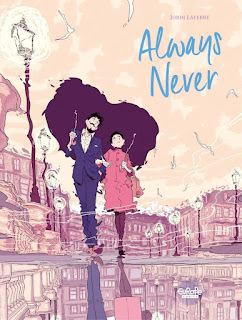

Lafebre tells this story in a mostly-sunny palette and with character designs that seem to my eye to have a bit of animation influence in them: these are people made to move through space, to interact with their world, to be dynamic in their bodies and faces. And even as Ana and Zeno end up on opposite sides of the world, we're on their side - on the side of each of them in their struggles, and on the side of wanting Ana-and-Zeno to be together. (Although Lafebre manages that in large part by keeping Ana's husband Giuseppe mostly in the background; his version of this story would be very different.)

Always Never is assured, confident, lovely, and sweet. It's also remarkably happy for a love story about two people who spend forty years about as far apart from each other as possible. I see it was the first book Lafebre wrote after drawing a number of bandes dessinées from other people's scripts; he's clearly been taking notes along the way.

No comments:

Post a Comment