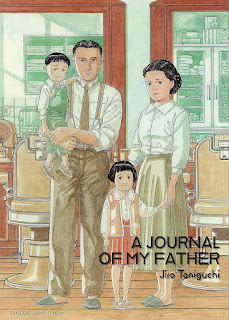

A Journal of My Father is his story, a twelve-chapter manga created in the mid-90s by Jiro Taniguchi, collected into one volume in Japan then and translated into English last year by Kumar Sivasubrmanian for Fanfare/Ponent Mon. In a way, it's about why Yoichi's was the wrong decision, or maybe, to be more subtle, about how he made that decision the wrong way and did it too strongly, how he cut off his father from most of his life.

It starts with Yoichi in middle age, somewhere near fifty in the early 1990s. His father has just died at the age of seventy-six, and Yoichi has to go back to Tottori, for the first time in fifteen years, to pay his respects. He expects it will be just that: a quick visit, as short and desultory as possible, and then he can get back to the real life he's built in Tokyo with his wife Ryoko.

Although, I should be honest: this is a very Japanese story, very 20th century, so the life Yoichi built is entirely based on work. Working all the time, morning to night, incessantly, to crowd out everything else in life. And, frankly, his father did the same. For all of the insights and thoughtful psychological depths A Journal brings to the story of Yoichi and his family, it never connects those two things, maybe because a fish will never ever mention water. Characters may point out similarities between the two men, but their common workaholic nature will never be seen as a negative: how could it be? Even when it caused the father's divorce and drove the son away forever?

The funeral is the frame story; most of the book is made up of flashbacks, things Yoichi remembers as he's sitting during the evening vigil, the night before the funeral, drinking sake and talking with his family. The flashbacks are pretty much entirely in sequence; Yoichi is remembering his childhood, his relationship with his father, from nearly the beginning.

And not his relationship with his mother, which is even more broken - she got a divorce when Yoichi and his older sister were in primary school, and basically never got to see the kids again. She, unlike the father, is still alive. This is a book about men and the relationship of fathers and sons; women are there, but in the workaholic world, they are not central. I do wonder why Yoichi doesn't have even a second to think that he could build a relationship with the parent who is still alive, while she is still alive.

I also wonder why Taniguchi has pointedly not given Yoichi any children of his own: that would have forced the story to open more, perhaps, to shift the focus from one man and his father. But it does mean we see Yoichi only, eternally, as a son.

Journal is a carefully-observed work, psychological complex, entirely real and honest. It's also embedded in a culture that is not my own, which has certain very strong expectations of what a man will do and say and feel - some of which Yoichi lived up to fully and some of which he did not. But, like all cultures, those expectations are not simple and easy: they were in conflict for Yoichi, and he picked the ones he felt were most important to him. Journal judges Yoichi fairly harshly, or it allows the judgements of others against him to stand unanswered. Taniguchi's afterword implies that he sees himself as something of a Yoichi, but his family was larger - Yoichi was the only son of his father, making him the only true heir.

Again, this is deeply sexist: Yoichi's sister did stick around Tottori, did learn hairdressing, did become part of the business - and all because she wanted to. But that is vastly less important than that Yoichi didn't. In many ways, A Journal is the story of people who can't see that their expectations for each other hurt them all for decades.

As I said: Fish. Water. They'll never tell you about it. You need to read with an eye for the patterns that are never mentioned, or you'll never see them. A Journal is full of patterns like that: it's a deep and rich book about people honestly depicted, living normal lives in a real world. It may make you think about different things than it did for me, but I expect it will make you think. And, as always, I recommend books that make you think.