It's important to check your assumptions against reality regularly: we often find that what we think is true actually has very little do with with what really happened.

Case in point: Ted McKeever.

I

had McKeever in my head as one of the great comics wild men, coming out

of nowhere with striking, original, and bizarre work in the late '80s,

briefly flourishing, and then disappearing from the scene entirely. In

my head, he was in the company of Marc Hansen and Bob Burden. Maybe

there was a hint of "too pure for this world," or some back-patting that

I liked his stuff even though the Great Unwashed didn't.

That is not exactly true. In fact, it's wrong in several ways: the person who lost touch was me.

McKeever's been out there the whole time, working away in comics. He

moved on to things I didn't pay much attention to, but that's all me,

not him.

So I remembered Transit and Eddy Current and Plastic Forks and Metropol, but I'd forgotten he went from there to illustrating part of Rachel Pollack's run on Doom Patrol

in the years of High Vertigo. (Which is a knock on me: I was fan of

both of them at the time, and I'm pretty sure I owned most of those

comics.) And, well, it's been more than twenty years since then, and

he's had new comics work out pretty much every one of those years,

according to Wikipedia.

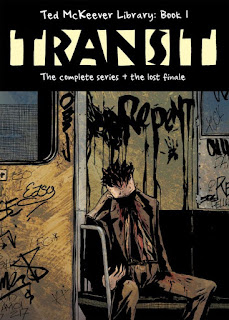

Also, because of that misconception, I had the vague sense that Transit was incomplete because it was the last thing McKeever did on his way out of comics. Again: totally wrong. Transit was McKeever's first

comics work, and it was left incomplete for reasons that aren't

explained in this 2008 collection. (But I think a huge part of the

explanation, for those of us who were around in the '80s, is that his

publisher was Vortex.)

Anyway, Transit had five

issues back in 1987-88, and then, twenty years later, those five issues

and "the lost finale" (from the different art style and radical shift in

tone, this was "lost" in the sense of "never actually drawn and

possibly not written until the 21st century") were collected into one

volume as part of a larger reprinting/rediscovery of McKeever's work

from Image's Shadowline imprint.

(The spine calls this book Ted McKeever Library Book 1: Transit The Complete Series, for you sticklers.)

Like

those other early McKeever books, it's the story of an ordinary guy in

an odd urban setting, with extraordinary events cascading around him and

a cast of quirky weirdos and creepy villains. It doesn't hold together

as well as say Eddy Current does, in large part because it didn't

have an ending for twenty years and now has one that's very muted and

distant, as if pieced together by scholars a hundred years later from

fragmentary contemporary accounts.

The guy is Spud. We

see him in a subway, casually vandalizing the posters of mayoral

candidates. Then he's shot (at?) by a cop and finds himself in the path

of a train. For several pages he seems to be dead, and the reader starts

to think he will not be our protagonist after all. But Spud does

show up again -- he's going to have much worse happen to him over the

next five issues than just being shot and run over by a subway.

There

is, of course, a corrupt man running for mayor. This was the '80s, so

I'm afraid that he's a preacher. And he's backed by the usual really fat

shadowy master-of-everything of this city, who sits in his palatial

office high up in an office tower. They are both not particularly

characterized beyond cackling about the evil things they are doing and

plan to keep doing. But McKeever had a very Munoz-esque -- maybe

filtered through Keith Giffen, maybe not -- appeal to his art at this

point, and evil men in dark rooms brings out the best of that art style.

Transit

is not a tightly plotted book: it starts from Spud and the nasty

mayoral election, and wanders around its grimy city from there, bringing

in more oddball characters and bouncing between energetic scenes that

don't always completely track to each other. It always makes it way back

to Spud and the evil guys eventually, more or less, but each loop seems

to have less and less to do with the initial setup. And then, of

course, we hit the "lost finale,"a series of quick scenes of the

characters, to close out all of their stories and provide something like

an ending. I don't think it's the ending McKeever was aiming for back

in 1988, but Transit feels like a book that was plotted as it went along, so I may be making an unwarranted assumption to say he was aiming for any particular ending.

In

any case, it's done now, such as it is, and available in one volume.

(Or was, a decade ago. It may be harder to find now.) McKeever got more

controlled and organized from here, but Transit shows the bones of the later stories -- it shows that McKeever was on his track from the beginning.

A Weblog by One Humble Bookman on Topics of Interest to Discerning Readers, Including (Though Not Limited To) Science Fiction, Books, Random Thoughts, Fanciful Family Anecdotes, Publishing, Science Fiction, The Mating Habits of Extinct Waterfowl, The Secret Arts of Marketing, Other Books, Various Attempts at Humor, The Wonders of New Jersey, the Tedious Minutiae of a Boring Life, Science Fiction, No Accounting (For Taste), And Other Weighty Matters.

Networks and Contacts

Who Is This Hornswoggler?

- Andrew Wheeler

- Andrew Wheeler was Senior Editor of the Science Fiction Book Club and then moved into marketing. He currently works for Thomson Reuters as Manager, Content Marketing, focused on SaaS products to legal professionals. He was a judge for the 2005 World Fantasy Awards and the 2008 Eisner Awards. He also reviewed a book a day multiple times. He lives with The Wife and two mostly tame children (Thing One, born 1998; and Thing Two, born 2000) in suburban New Jersey. He has been known to drive a minivan, and nearly all of his writings are best read in a tone of bemused sarcasm. Antick Musings’s manifesto is here. All opinions expressed here are entirely those of Andrew Wheeler, and no one else. There are many Andrew Wheelers in the world; this may not be the one you expect.

The Latest Editorial Explanations

Previously on Antick Musings...

-

▼

2017

(218)

-

▼

September

(20)

- Hershey by Michael D'Antonio

- Glister by Andi Watson

- Transit by Ted McKeever

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 9/23

- Notes, Vol. 1: Born to Be a Larve by Boulet

- I Told You So by Shannon Wheeler

- All Systems Red by Martha Wells

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 9/16

- Troll Bridge by Neil Gaiman and Collen Doran

- Contrary To Popular Believe by Joey Green

- Dragons: The Modern Infestation by Pamela Wharton ...

- Black Dahlia by Rick Geary

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 9/9

- Kyle Baker, Cartoonist, Volume 2: Now With More Ba...

- White Noise by Don DeLillo

- Early Stories: 1977-1988 by Rick Geary

- Paul Up North by Michel Rabagliati

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 9/2

- Incoming Books: August 31

- Read in August

-

▼

September

(20)

My Life As a Twit

Hornswogglets

Recurring Motifs

- 246 Different Kinds of Cheese (119)

- A Series of Tubes (50)

- Abandoned Books (8)

- Adaptations (6)

- All Knowledge Is Found In Fandom (15)

- All of This and Nothing (9)

- Alternate History (8)

- Amazon Pimpage (80)

- America Fuck Yeah (3)

- Art Books (32)

- Awards (227)

- Backwards Glances (1)

- Belated Review Files (41)

- Better Things (53)

- Blog in Exile (78)

- Blogging About Blogging (263)

- Book Marketing 101 (5)

- Book-A-Day (1319)

- Books Do Furnish a Room (9)

- Books Read (258)

- Brain and Brain What Is Brain (2)

- Burned Book Contest (5)

- Candy (1)

- Captain Underpants (7)

- CauseWired (1)

- Circles of Hell (3)

- Class War Follies (6)

- ComicMix (222)

- Comics (2439)

- Confuse-o-vision (5)

- Conventions (59)

- Corrections (6)

- Crazy People (10)

- Critics and Their Criticism (2)

- Crowds and Their Funding (1)

- Deep Dark Secrets (13)

- Deep Thoughts (287)

- Don't Talk to Me About Love (2)

- Dungeon Fortnight (20)

- Editorial Explanations (13)

- Eisners (14)

- Exceptional Writers (2)

- Famous (4)

- Fan Fiction (8)

- Fanciful Family Anecdotes (41)

- Fandom (11)

- Fantasy (712)

- Favorites of the Year (32)

- Flame Bait (3)

- Food Porn (10)

- Foreigners Sure Are Foreign (319)

- Free Stuff (18)

- Gadgets and Gewgaws (13)

- Grammar (4)

- Great Mass Movements of Our Time (12)

- Great SF Novels of 1990s (4)

- Hard Case (8)

- High Finance (29)

- Holidays (90)

- Hornswoggler's Estleman Loren Project (15)

- Horrible Images That Will Never Leave Your Brain (12)

- Horror (87)

- House Rules (2)

- Hugo Thoughts (16)

- Humor: Analysis Of (291)

- Humor: Attempts At (61)

- I Love (And Rockets) Mondays (33)

- I Never Metafiction I Didn't Like (7)

- In Memoriam (23)

- Incoming Books (248)

- Inexplicable Occurences (8)

- Infographics (3)

- Interviews (12)

- It Must Be Mine (7)

- It's Only The End of the World Again (1)

- It's the Economy Stupid (51)

- Itzkoff (37)

- J'Accuse (2)

- James Bond Daily (59)

- Kids Today (1)

- Lego (11)

- Lies Damned Lies & Statistics (1)

- Linkage (873)

- Literature (193)

- Live Theater (8)

- Lurking Under Bridges (3)

- Magazines (8)

- Maps and Territories (1)

- Matters of Commerce (103)

- Measurements (1)

- Meme-o-riffic (212)

- Memoirs (85)

- Movie Log (352)

- Music (268)

- Mystery (185)

- Nature Red in Tooth and Claw (2)

- Navel-Gazing (1)

- Networks of Socialists (1)

- New York Times (20)

- No Context For You (3)

- Non-Fiction (467)

- Notable Quotables (107)

- Numbers Wonkery (10)

- O Canada (16)

- Obscure (4)

- Old Posts Resurrected (82)

- One of Us One of Us (5)

- Pedantry (4)

- Podcasts (4)

- Poetry (18)

- Politics (45)

- Polls (3)

- Portions for Foxes (54)

- Quizzes (1)

- Quora (1)

- Quote of the Week (833)

- Rants (111)

- Reading Into the Past (100)

- Reading Neepery (22)

- Reading Projects (1)

- Realms of Fantasy (3)

- Reportage (26)

- Reviewing the Mail (782)

- Reviews (3234)

- Rising Suns (23)

- Romance (8)

- Royalty (1)

- Saturday Is Bond Day (18)

- Scandals (4)

- Schadenfreude (4)

- Science Fiction (651)

- Secret Arts of Marketing (52)

- Self-Indulgence (1)

- SFF Art (30)

- SFWA (8)

- Short Fiction (43)

- Skeletons in the Attic (1)

- Skiffy (1)

- Smouldering Masses of Stupidity (40)

- Smutty (84)

- Snap Snap Wink Wink Grin Grin (5)

- Snark (16)

- Spam (6)

- Splendors of Publishing (351)

- sports (4)

- Starktober (33)

- Such A Deal I Have For You (6)

- Techno-Wonkery (13)

- Tedious Minutiae of a Boring Life (352)

- That Old-Time Religion (6)

- The Criminal Mind (4)

- The First Thing We Do Let's Kill All the Lawyers (6)

- The Great Idiot Box (6)

- The Horrors of Geography (1)

- The Joys of Bookselling (73)

- The Making of Lists (33)

- The Past Is a Foreign Country (277)

- The War Between Men and Women (29)

- The Working Life (11)

- there (1)

- There Will Always Be an England (73)

- This Year (53)

- Those Crazy College Kids (4)

- Thrilling Tales of Science (15)

- Tie-Ins (1)

- Towering Stacks of Unread Books (14)

- Travel Broadens The Mind Until You Can't Get Your Head Out the Door (100)

- True Names (3)

- Twelve Days of Commerce (17)

- Universal Laws (2)

- Video Killed the Radio Star (3)

- Vintage Contemporaries (19)

- Western (4)

- WFA Judgery (57)

- What These People Need Is a Honky (1)

- Wide World of Wheelers (9)

- Widgets (2)

- Wonders of New Jersey (42)

- Words Words Words (30)

- Years of Unremitting Toil (2)

- Years Prematurely Declared to Be Over (3)

- You Know: For Kids (307)

No comments:

Post a Comment