And by "you," I mean "me," obviously.

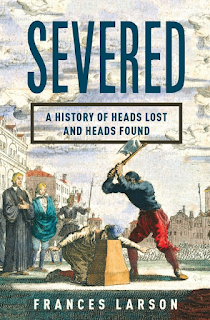

It might take you four years after publication to get a copy. It might take four more years for the thing to push its way to the top of the to-be-read piles. But, damn it, you are going to read the book about severed heads.

Severed is from 2014, in case the math in the previous paragraph is giving you trouble. Its author Frances Larson has had at least one more book since then, and seems to still be around as a respected British anthropologist and writer; from a quick Googling, it looks like she may be in Oxford rather than Durham these days.

And I'll let her give the why - or one of the whys:

A severed head can be many things: a loved one, a trophy, scientific data, criminal evidence, an educational prop, a religious relic, an artistic muse, a practical joke. It can be an item of trade, a communication aid, a political pawn or a family heirloom; and it can be many of these things at once. Its definitions are unstable and they oscillate dramatically, which is one of the reasons human remains have the power to unsettle us. They impose themselves and challenge our assumptions, and none more so than the human head, whose eyes meet our own.

(p.10)

Severed is divided, as many relatively serious non-fiction books are, into thematic chapters. Larson's themes, obviously, are all about the various ways and reasons and historical contexts in which a head might be separated from its neck, and the uses those heads (and various sub-components of the head) could be put to afterward. So she starts with a prologue about one of the most famous heads, that of Oliver Cromwell, before a short introduction covering quickly many of the things she will go into in more depth later. The eight main chapters cover, roughly: shrunken heads, trophies taken in war (especially the Pacific war of WWII), executions both official (especially French, especially with the guillotine) and criminal (particularly those videotaped by terrorists and broadcast to the world), the severed head in and as art, heads as religious artifacts, skulls (mostly famous), dissection and brains, and the efforts to determine how long (or if) consciousness persists after beheading.

Some themes and ideas recur across multiple chapters, of course. It's all about severed heads, after all: some of the characters will come back to sever heads in other contexts. [1]

I struggle to find the right adjectives to describe Severed. Larson is a deeply informed, agile writer, and I found her very quotable and always insightful. But it would be wrong to describe the resulting book as "wonderful" (though it definitely does provide wonders) or "engrossing" (though there is much that readers will find...gross).

I doubt there will ever be another major nonfiction book on severed heads. Luckily for all of us, this one is magnificent and comprehensive. If you are anything like me, just knowing this book exists will induce you to add it to your list. If you are nothing like me, I apologize for taking up so much of your time. You should also avoid this blog for the next two days, when there will be quotes from Severed that I presume will also be unpleasant for you.

[1] I couldn't find an obvious way to fit this into the body of the post, so let me stick it here:

In the decades either side of 1900, scientists started to donate their brains to each other, so much so that bequeathing your brain to your colleagues became something of a 'cottage industry.' Formal and informal 'brain clubs' sprang up in Munich, Paris, Stockholm, Philadelphia, Moscow and Berlin, where distinguished members agreed to leave their brains to their fellow anatomists, who expressed their gratitude by reading out the results of their investigations to other members of the club. One of the most famous was the Paris Mutual Autopsy Club, which was founded in 1872. Members could die happy in the knowledge that their own brain would become central to the utopian scientific project they had pursued so fervently in life.

(pp.233-234)

If there isn't already a death metal band named Paris Mutual Autopsy Club, I despair for the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment