That said, there is a representative of what seems to be a government who appears briefly in Finder: Dream Sequence. And we also see some bureaucratic maneuverings involving the ownership and organization of a big, profitable corporation. (And, as you know, Bob, corporations are creatures of the law: outside of that framework, even the best-organized and -focused group for maximizing profit is just a gang.) Perhaps McNeil is just not all that interested in depicting governance, but does have some ideas of how these domed cities rule themselves - I'm imagining something like the Doge and Great Council of Venice, where the local clans would have somewhat equal weight and there's some single figure to make the final decisions. But that would be on the individual city level, since McNeil has made it very clear they are each separate entities. And the clans tend to cluster, I think: each city has a few clans that are dominant, with others in smaller numbers. So I still think inter-city conflicts are still very likely, unless this world is so depopulated that thousands of miles separate what is only a handful of cities in the world.

(And, frankly, a lot of this world still reads to me as a horrible dystopia. Wastelands full of semi-feral tribes living Hobbesian lives. City people forced into straitjacket lives because their clan only can do three careers. Plus late capitalism in all its splendor and horrors, almost the same as in our world.)

But worlds don't need to be perfect, or wonderful, or even tolerable: they need to be interesting places where stories can happen. And Finder has that in spades.

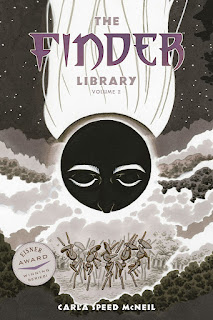

Dream Sequence is the first book collected in the second omnibus, The Finder Library, Vol. 2. I read the first omnibus all in a rush, but I think I'm going to take these stories one-by-one.

The main character is Magri White, a tormented young genius who creates and maintains the VR realm Elsewhere in his head. Finder has a theory of mind that draws as much on '50s psionics as on '80s cyberpunk, so White was driven into this world by the weight of hearing everyone else's unpleasant mental chatter as a child - specifically chatter about him, and particularly negative chatter, so it's not entirely clear if this was real or his self-loathing assumptions - all of the time. McNeil presents this all in a SFnal context, and her characters have extensive brain augmentation and computer-connection available, so this is all "real" on some level: maybe psychological, maybe actual brain-to-brain communication. The people of this particular domed city - I think it's still Anvar, the site of most of the series to date - are often extensively brain-jacked, for both work and entertainment.

(McNeil, in her notes, also says "I don't think the voices Magri heard all the way back to age five were anything unusual," which implies she has a very different experience of life: I've never known anyone who claimed to hear other people's thoughts in their heads, and I would generally consider a person who did say that to be unbalanced at best.)

So: Magri has created a large, detailed, seemingly real place, which is hugely popular because it's the only one of its kind. Other VR realms are built on computers and maintained by computers; his is organic and clearly more human. A vast corporation, originally started by his distant, cold parents, has grown up around Elsewhere; Magri owns it but whether he could control it, even if he were less of a distracted tormented-artist type, is less clear. In fact, we see the be-suited men who run the corporation, who treat Magri as an annoyance and a resource to be exploited, the fallibly organic substrate that eternally complicates their crisp budget projections and plans and goals. Their schemes drive much of he plot of Dream Sequence; this is largely the story of how changes in Elsewhere provoke crises, how those suits plan to respond, and how Magri finally does something active, in both his interior and exterior world, for the first time in more than a decade.

From the beginning of Dream Sequence, we know something is wrong with Elsewhere: some malevolent force is stalking and maiming visitors there. McNeil uses that opportunity to play some interesting variations on the old "if you die in VR, you die in real life" standard. We see that Magri is coming more and more unglued: Elsewhere is him, so whatever is wrong with it must be coming from him in some way.

The suits find a scapegoat to blame the violence on - an actual person who looks something like the figure in Elsewhere, who as far as we can tell has nothing to do with it. (It's Jaeger, McNeil's main continuing character, which her notes had to tell me - he barely talks, doesn't get a name in the story pages, looks completely different, and his role here is purely as an innocent scapegoat.)

In the end, Magri does face the source of the problem head-on, takes responsibility and control, and moves forward: the ending we hoped for and wanted.

That's all the what of this story. What makes it special - why McNeil gets such rapturous reviews and glowing quotes - is the how. She's a magnificent artist and a thoughtful writer; this book is filled with complex pages that read precisely, with masses of background text and visionary images, long dialogue and monologue sequences, and a parade of amazing imagery, here set free by the possibilities of Elsewhere as a VR realm in general and its breaking down in particular. This is a deep, intense story on a subject very close to its creator, about trauma and creation and the terror of being in the spotlight, family and escapism and the rapacity of capitalism. I can quibble about some details - I did, of course - but it forms into a complete, self-consistent, inspiring whole.

[1] See my post on The Finder Library, Vol. 1, which collects the first three storylines, for more details, and some background on the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment