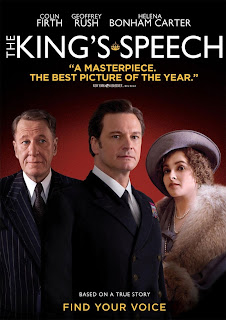

I'm sure someone, somewhere, has begun a review of this movie by imitating stuttering in print. "I'd like to t-t-t-t-talk ab-b-b-b-b-bout The King's S-s-s-s-speech," perhaps. So, since that slot has already been filled, I don't need to be That Guy, which is a relief. (Because That Guy is a jerk, and not funny, either.)

The King's Speech is a very high-minded, serious, life-affirming movie, of the kind that the English film industry loves to make -- probably because the American public, and the public of many other countries, including their own, eats it up every time -- and it will be deeply familiar and utterly unsurprising to anyone who has seen more than a dozen movies in his life. (Let along being even vaguely familiar with WWII, or the recent history of the British monarchy.)

It's all very nice, full of plummy accents, understated posh surroundings, stiff upper lips, and predictable uplift. Movies like this have been winning piles of Oscar awards for eight or nine decades, and there's no sign that the Academy of 2035 will buck that trend, either. The King's Speech is a movie to make adults feel smart and superior and cultured without having to read subtitles, learn anything substantial, or actually consider any unpleasant things existing in the world, now or ever.

Colin Firth plays the younger brother of a bad father whom he nevertheless utterly loves, in the way that only tortured-in-public-school British aristocrats can love their families. (Which is to say: completely undemonstratively.) And he's going to be King as soon as that bad father dies and as soon as his equally-bad-in-other-ways older brother decides to abdicate in favor of marrying an American divorcee. Of course, Firth's Prince Bertie is both utterly devoted to his duty and scared to death of it, which makes him perfect for audience-identification purposes: speaking in public is the #1 fear, so a story about a really rich and powerful guy with that fear (and for a good reason!) is a guaranteed hit.

And so on and on; Geoffrey Rush is the obligatory oddball guru, whose unusual methods dependably deliver the results that the stuffed-shirt "establishment" types can't. And Helena Bonham Carter is given very little to do as the future Queen Mum, but she does it as stiff-upper-lippy as possible. In fact, the story of The King's Speech is so tailor-made for a big feel-good movie that one has to wonder why it wasn't made twenty or thirty years ago, probably by Merchant-Ivory. But it did eventually become the movie that was destined to exist, and now destiny won't rest until we all see it. It's a perfectly pleasant two hours of exposed celluloid, so you might as well get it over with, if you haven't already.

A Weblog by One Humble Bookman on Topics of Interest to Discerning Readers, Including (Though Not Limited To) Science Fiction, Books, Random Thoughts, Fanciful Family Anecdotes, Publishing, Science Fiction, The Mating Habits of Extinct Waterfowl, The Secret Arts of Marketing, Other Books, Various Attempts at Humor, The Wonders of New Jersey, the Tedious Minutiae of a Boring Life, Science Fiction, No Accounting (For Taste), And Other Weighty Matters.

Networks and Contacts

Who Is This Hornswoggler?

- Andrew Wheeler

- Andrew Wheeler was Senior Editor of the Science Fiction Book Club and then moved into marketing. He currently works for Thomson Reuters as Manager, Content Marketing, focused on SaaS products to legal professionals. He was a judge for the 2005 World Fantasy Awards and the 2008 Eisner Awards. He also reviewed a book a day multiple times. He lives with The Wife and two mostly tame children (Thing One, born 1998; and Thing Two, born 2000) in suburban New Jersey. He has been known to drive a minivan, and nearly all of his writings are best read in a tone of bemused sarcasm. Antick Musings’s manifesto is here. All opinions expressed here are entirely those of Andrew Wheeler, and no one else. There are many Andrew Wheelers in the world; this may not be the one you expect.

The Latest Editorial Explanations

Previously on Antick Musings...

-

▼

2011

(391)

-

▼

May

(44)

- Working Accounting Hours

- The Infinities by John Banville

- Keep the Change by Steve Dublanica

- Movie Log: Megamind

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 5/28

- Dungeon Quest Book One by Joe Daly

- Movie Log: Wild Target

- Incoming Books: May 27, 2011

- Movie Log: Harry Potter #7.1

- Naruto 49 & 50 by Masashi Kishimoto

- Quotes of the Week: Women and the Men Who Glare at...

- The Complete Bloom County Library, Volume Two: 198...

- The Perils of Too Many Books

- Nebula Winners for 2011

- Where I'll Be in June

- Hugo Thoughts

- Incoming Books: May 23, 2011

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 5/21

- In Which I Pose as a Physics Teacher

- Quotes of the Week: The Day the World Ended

- Characteristic Ages of Genres

- Getting Out of the House

- Savage Chickens by Doug Savage

- Reunion by Pascal Girard

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 5/14

- Locus Awards "Finalists"

- The Mistressworks of SF

- Movie Log: The King's Speech

- Quote of the Day

- Quote of the Week: Life in Hell

- The Final Solution by Michael Chabon

- Another Punt

- Musings and Meditations by Robert Silverberg

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 5/7

- A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan

- Dick and Clarke Winners

- Quote of the Week: Asch on Writing

- Ways To Know You're In Florida, # 7126

- Memories of an Ill-Spent Youth

- Reason Why My Wife Is Awesome of the Day

- The Wonders of Technology

- Reviewing the Mail: Week of 4/30

- Incoming Books: last week of April 2011

- Read in April

-

▼

May

(44)

My Life As a Twit

Hornswogglets

Recurring Motifs

- 246 Different Kinds of Cheese (121)

- A Series of Tubes (50)

- Abandoned Books (8)

- Adaptations (6)

- All Knowledge Is Found In Fandom (15)

- All of This and Nothing (10)

- Alternate History (8)

- Amazon Pimpage (80)

- America Fuck Yeah (3)

- Art Books (32)

- Awards (227)

- Backwards Glances (1)

- Belated Review Files (41)

- Better Things (53)

- Blog in Exile (78)

- Blogging About Blogging (263)

- Book Marketing 101 (5)

- Book-A-Day (1319)

- Books Do Furnish a Room (9)

- Books Read (258)

- Brain and Brain What Is Brain (2)

- Burned Book Contest (5)

- Candy (1)

- Captain Underpants (7)

- CauseWired (1)

- Circles of Hell (3)

- Class War Follies (6)

- ComicMix (222)

- Comics (2444)

- Confuse-o-vision (5)

- Conventions (59)

- Corrections (6)

- Crazy People (10)

- Critics and Their Criticism (2)

- Crowds and Their Funding (1)

- Deep Dark Secrets (13)

- Deep Thoughts (287)

- Don't Talk to Me About Love (2)

- Dungeon Fortnight (20)

- Editorial Explanations (13)

- Eisners (14)

- Exceptional Writers (2)

- Famous (4)

- Fan Fiction (8)

- Fanciful Family Anecdotes (41)

- Fandom (11)

- Fantasy (712)

- Favorites of the Year (32)

- Flame Bait (3)

- Food Porn (10)

- Foreigners Sure Are Foreign (323)

- Free Stuff (18)

- Gadgets and Gewgaws (13)

- Grammar (4)

- Great Mass Movements of Our Time (12)

- Great SF Novels of 1990s (4)

- Hard Case (8)

- High Finance (29)

- Holidays (90)

- Hornswoggler's Estleman Loren Project (15)

- Horrible Images That Will Never Leave Your Brain (12)

- Horror (87)

- House Rules (2)

- Hugo Thoughts (16)

- Humor: Analysis Of (292)

- Humor: Attempts At (61)

- I Love (And Rockets) Mondays (33)

- I Never Metafiction I Didn't Like (7)

- In Memoriam (23)

- Incoming Books (248)

- Inexplicable Occurences (8)

- Infographics (3)

- Interviews (12)

- It Must Be Mine (7)

- It's Only The End of the World Again (1)

- It's the Economy Stupid (51)

- Itzkoff (37)

- J'Accuse (2)

- James Bond Daily (59)

- Kids Today (1)

- Lego (11)

- Lies Damned Lies & Statistics (1)

- Linkage (873)

- Literature (193)

- Live Theater (8)

- Lurking Under Bridges (3)

- Magazines (8)

- Maps and Territories (1)

- Matters of Commerce (103)

- Measurements (1)

- Meme-o-riffic (212)

- Memoirs (85)

- Movie Log (352)

- Music (269)

- Mystery (186)

- Nature Red in Tooth and Claw (2)

- Navel-Gazing (1)

- Networks of Socialists (1)

- New York Times (20)

- No Context For You (3)

- Non-Fiction (468)

- Notable Quotables (107)

- Numbers Wonkery (10)

- O Canada (16)

- Obscure (5)

- Old Posts Resurrected (82)

- One of Us One of Us (5)

- Pedantry (4)

- Podcasts (4)

- Poetry (18)

- Politics (45)

- Polls (3)

- Portions for Foxes (54)

- Quizzes (1)

- Quora (1)

- Quote of the Week (835)

- Rants (111)

- Reading Into the Past (100)

- Reading Neepery (22)

- Reading Projects (1)

- Realms of Fantasy (3)

- Reportage (26)

- Reviewing the Mail (783)

- Reviews (3242)

- Rising Suns (23)

- Romance (8)

- Royalty (1)

- Saturday Is Bond Day (18)

- Scandals (4)

- Schadenfreude (4)

- Science Fiction (656)

- Secret Arts of Marketing (52)

- Self-Indulgence (1)

- SFF Art (30)

- SFWA (8)

- Short Fiction (43)

- Skeletons in the Attic (1)

- Skiffy (1)

- Smouldering Masses of Stupidity (40)

- Smutty (84)

- Snap Snap Wink Wink Grin Grin (5)

- Snark (16)

- Spam (6)

- Splendors of Publishing (351)

- sports (4)

- Starktober (33)

- Such A Deal I Have For You (6)

- Techno-Wonkery (13)

- Tedious Minutiae of a Boring Life (352)

- That Old-Time Religion (6)

- The Criminal Mind (4)

- The First Thing We Do Let's Kill All the Lawyers (6)

- The Great Idiot Box (7)

- The Horrors of Geography (1)

- The Joys of Bookselling (73)

- The Making of Lists (33)

- The Past Is a Foreign Country (280)

- The War Between Men and Women (29)

- The Working Life (11)

- there (1)

- There Will Always Be an England (74)

- This Year (53)

- Those Crazy College Kids (4)

- Thrilling Tales of Science (15)

- Tie-Ins (1)

- Towering Stacks of Unread Books (14)

- Travel Broadens The Mind Until You Can't Get Your Head Out the Door (100)

- True Names (3)

- Twelve Days of Commerce (17)

- Universal Laws (2)

- Video Killed the Radio Star (3)

- Vintage Contemporaries (19)

- Western (4)

- WFA Judgery (57)

- What These People Need Is a Honky (1)

- Wide World of Wheelers (9)

- Widgets (2)

- Wonders of New Jersey (42)

- Words Words Words (30)

- Years of Unremitting Toil (2)

- Years Prematurely Declared to Be Over (3)

- You Know: For Kids (307)

No comments:

Post a Comment